Matthew VanDyke joins us for a final installment about his time spent as a freedom fighter in Libya. As a former Special Forces Weapons Sergeant, I couldn’t help but pick his brain a bit about the weapons used during the Libyan Civil War.

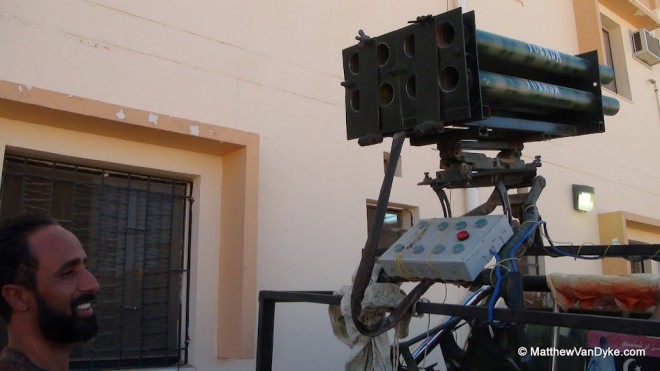

Many of us were impressed by the DIY improvisation of the rebels. What kind of expertise did the builders of these devices (remote control guns, home made rocket launchers, ect…) have before hand and what was the learning curve like. How did these improvised weapons preform in combat?

“The devices were very impressive, but not particularly complex. The rocket launchers were steel pipes, wiring, a simple push-button panel, and an automotive battery. They made bullet shields out of steel plating.

One of the rebels in charge of ammunition for our brigade showed me once how he had started taking warheads from one rocket system and using them for another that he had a shortage of warheads for, making them compatible by using a pipe fitting to connect the warhead to the rocket.

I met another rebel who used to be an Air Force pilot for Gaddafi with an interesting technical background (he had once modified communications equipment in his MiG to pick up NATO transmissions, which when discovered by the Soviets led them to complain to the Libyan government about modifying the MiGs). He retired many years ago and used his technological proficiency during the war to modify GRAD rockets for increased range, and developed a rocket launcher that could be rotated after firing to launch another salvo of rockets at a different firing angle. He showed me a hundred year old Continsouza M-16 rifle he had modified with a modern sniper scope, and had calibrated it by laser and test firing. The guy was like Q from the James Bond films, a brilliant man.”

What weapons performed well and which didn’t? I saw in some of your pictures that you had FN P90 Sub-machine guns and the newer FS 2000 rifle that I assume you captured from Libyan forces…

“The AK-47 of course always performed well. Not all of the rebels knew how to clean their weapons, and although we had a unit from Ajdabiya that performed a cleaning service, it was good to have reliable, low maintenance AK-47s. I met a rebel who had a FN FAL, and when I saw him later in the war he had an AK-47. When I asked him what happened to the FN, he said he traded it for the AK-47 because the FN needed too much cleaning.

I mostly served as a DShK gunner on the KADBB Desert Iris jeep, with my Libyan friend Nouri Fonas as the driver (we have known each other for four years, having met in Mauritania in 2007). I had a FN FAL captured brand new from a Gaddafi stockpile near Sirte. I usually carried my AK-47 though because of the reliability factor and greater ammo capacity.

I also used a PKT machine gun (that had been taken off a tank and thus lacked a stock, and had a steel bar welded onto it as a grip) and a FN F2000 in combat a few times. They both belonged to Nouri’s brother and were on loan to us. I also used a RPG in combat that belonged to another rebel.

I had no major problems with the AK-47 or the FN FAL during the war. I always considered my FN FAL to be what I used when I needed greater accuracy, and my AK-47 is what I usually kept on me at all times as my always dependable weapon.

We had some problems with the PKT because it would get dirty, and stoppages caused by rounds being misaligned in the ammo belt.

The DShK was dangerously unreliable. Ours needed a good amount of oil at times to avoid stoppages. This caused problems a few times, and a rebel once told me that many rebels were killed during the war because of DShK problems.

The FN F2000 was reliable, but ammunition for it was very scarce. I mostly used it for the 40mm grenade launcher. I carried it for the grenade launcher several times before we even found a mag for it. I think many of the rebels were under the false impression that it was a sniper rifle because it had a scope. I had no problems with the Russian-made RPG launcher either.

At the beginning of the war we had found a couple of 60mm mortar tubes made in the USA in the 1940s, and a Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. bipod for one of them. We found these at the Rajma weapons storage facility base, and they had survived the aerial bombing of the base a few days earlier. I called a US Special Forces soldier [not this editor -Jack] I knew in the states to ask for basic advice about mortars. Our group in March had planned to use these mortars during the war, but never got the chance because of the ambush in Brega.

I never saw a P90 used during combat. The P90 I was photographed with was the only one I ever saw. It was in Sirte, but I never fired it, and never saw anyone fire it.

The Ajdabiya weapons service team were amazing. They had a large truck with an air compressor they used to clean weapons with a diesel fuel and compressed air spray. They and others made repairs and modifications to weapons that were essential to keeping them in service. They were some of the most brilliant and hardworking rebels in the war.”

You mentioned that there was a specialized cell that serviced weapons out on the front lines, were there any other specialty units, and did these units self organize organically or how did they come about?

“The weapons repair and service units appeared to have just gotten together on their own. The main one on the east side were a group from Ajdabiya city with a variety of backgrounds. They were mostly weapons cleaning and servicing. The more mechanic and serious weapons repair group were not from Ajdabiya I don’t think, but they also appeared to just develop organically. I don’t think either of these units were under the direction of the NTC or any katiba (brigade). They just showed up each day at a rally point behind the front lines and everyone knew where to find them. I stayed at the house they were using in Sirte a couple of times and got to know them fairly well. Without them the war would have been very difficult. They were indispensable.

Food and water supply was handled the same way it appeared. Trucks would just show up with plastic bags of food (mostly juice boxes, packaged sweet pastries, etc.), occasionally hot food in containers, and bottles of water. There were also the civilian volunteers who would bring pickup trucks near the front lines and serve us food, water, etc. out of the back of the truck.

There were also women making meals, which would then be brought to the front. Occasionally they would contain little pieces of paper with sayings in Arabic to encourage us. It was very inspiring.

It really was a war effort, and so many people got involved to support us. When there was a need people showed up to fill it. One time a truck showed up and delivered shoes (with KBR label on the boxes, not sure if it was THAT KBR or not, I have pictures and video) because some rebels didn’t have good shoes.

On the west side they had a snack bar with men serving coffee, making sandwiches, and once I saw them giving away packets of cigarettes. It was an organized operation. I think it was mostly intended to service the medics and journalists, but others ate there sometimes as well (including Nouri and I).

There wasn’t enough organization to really accomplish this in any other way than people stepping up to fill needs as they arose. It was an incredible thing to see.

I am not sure where exactly the food and water was coming from or who coordinated the supply lines. I was just glad they were there. Our commander gave Nouri and I control of the jeep to use as we saw fit, which meant that when our brigade was awaiting orders, etc., Nouri and I would go and fight alongside other brigades as well. This meant we had many engagements with the enemy, but being out on our own so much also meant that we didn’t spend as many days at our brigade’s base and weren’t around for meal times. I know that the brigades knew when and where the supplies would be and were well supplied, but Nouri and I were in a special situation since we often operated independently of the brigade, and since we were on our own and away from the brigade so often we ended up eating with other rebels or finding our own food.”

There is a still a lot of skepticism about the future of Libya, not to mention the Arab Spring in general, but what is your personal opinion about the future for democracy in this region?

“The region will have democracy. Islamists will win the first few elections because they’re already organized and will be better at playing politics than their secular opponents. The populations of recently liberated countries will tend to be more religious, as the violence, hardship, and loss during war tends to make people embrace religion more. As a result the Islamists will do well at the polls at first, which is actually a good thing. It is far better to have them integrated into the political process than outside of it where they’re more likely to use violence or subterfuge in seeking power. Once they realize that the new war is political and they can be victorious working peacefully within the system (and benefiting from the perks and corruption of it as well), they will embrace politics.

Given the pace of secularization worldwide (accelerated by access to the internet and Western popular culture), Islamists won’t dominate politics for more than a few election cycles. The youth of the Arab world want many of the same things that Western youth want (including the vices), and they have little desire to live under the thumb of Islamists. Additionally Islamists aren’t necessarily skilled at governance, and when they govern poorly they’ll be voted out of power.

But in the end, it is up to the people of these countries to decide their future at the ballot box. Beyond advocating for democracy and helping them to achieve it, it isn’t my place, or anyone else’s, to tell them who to elect or who not to elect. If they want to elect an Islamic government so be it, and we’re free to then interact diplomatically with that government however we see fit for our interests. Trying to influence politics in these countries is a very risky game that is unlikely to work, and might backfire.

Nothing can stop the Arab Spring, and it will spread to an Iranian Spring, African Spring, and Asian Spring. The 21st century will be the century of freedom. I am confident that there won’t be an authoritarian regime left in the world by the mid-21st century.”

A huge thank you to Matthew VanDyke for sharing his incredible story with us and educating us about what was really happening on the ground in Libya. I find that these boots on the ground accounts are particularly enlightening to all of us here in America who had the often dubious mainstream media to rely upon for information. You can find Matt at his

blog and freedom fighting, and also on

Twitter and

Facebook.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Matthew VanDyke joins us for a final installment about his time spent as a freedom fighter in Libya. As a former Special Forces Weapons Sergeant, I couldn’t help but pick his brain a bit about the weapons used during the Libyan Civil War.

Many of us were impressed by the DIY improvisation of the rebels. What kind of expertise did the builders of these devices (remote control guns, home made rocket launchers, ect…) have before hand and what was the learning curve like. How did these improvised weapons preform in combat?

“The devices were very impressive, but not particularly complex. The rocket launchers were steel pipes, wiring, a simple push-button panel, and an automotive battery. They made bullet shields out of steel plating.

One of the rebels in charge of ammunition for our brigade showed me once how he had started taking warheads from one rocket system and using them for another that he had a shortage of warheads for, making them compatible by using a pipe fitting to connect the warhead to the rocket.

I met another rebel who used to be an Air Force pilot for Gaddafi with an interesting technical background (he had once modified communications equipment in his MiG to pick up NATO transmissions, which when discovered by the Soviets led them to complain to the Libyan government about modifying the MiGs). He retired many years ago and used his technological proficiency during the war to modify GRAD rockets for increased range, and developed a rocket launcher that could be rotated after firing to launch another salvo of rockets at a different firing angle. He showed me a hundred year old Continsouza M-16 rifle he had modified with a modern sniper scope, and had calibrated it by laser and test firing. The guy was like Q from the James Bond films, a brilliant man.”

What weapons performed well and which didn’t? I saw in some of your pictures that you had FN P90 Sub-machine guns and the newer FS 2000 rifle that I assume you captured from Libyan forces…

“The AK-47 of course always performed well. Not all of the rebels knew how to clean their weapons, and although we had a unit from Ajdabiya that performed a cleaning service, it was good to have reliable, low maintenance AK-47s. I met a rebel who had a FN FAL, and when I saw him later in the war he had an AK-47. When I asked him what happened to the FN, he said he traded it for the AK-47 because the FN needed too much cleaning.

I mostly served as a DShK gunner on the KADBB Desert Iris jeep, with my Libyan friend Nouri Fonas as the driver (we have known each other for four years, having met in Mauritania in 2007). I had a FN FAL captured brand new from a Gaddafi stockpile near Sirte. I usually carried my AK-47 though because of the reliability factor and greater ammo capacity.

I also used a PKT machine gun (that had been taken off a tank and thus lacked a stock, and had a steel bar welded onto it as a grip) and a FN F2000 in combat a few times. They both belonged to Nouri’s brother and were on loan to us. I also used a RPG in combat that belonged to another rebel.

I had no major problems with the AK-47 or the FN FAL during the war. I always considered my FN FAL to be what I used when I needed greater accuracy, and my AK-47 is what I usually kept on me at all times as my always dependable weapon.

We had some problems with the PKT because it would get dirty, and stoppages caused by rounds being misaligned in the ammo belt.

The DShK was dangerously unreliable. Ours needed a good amount of oil at times to avoid stoppages. This caused problems a few times, and a rebel once told me that many rebels were killed during the war because of DShK problems.

The FN F2000 was reliable, but ammunition for it was very scarce. I mostly used it for the 40mm grenade launcher. I carried it for the grenade launcher several times before we even found a mag for it. I think many of the rebels were under the false impression that it was a sniper rifle because it had a scope. I had no problems with the Russian-made RPG launcher either.

At the beginning of the war we had found a couple of 60mm mortar tubes made in the USA in the 1940s, and a Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. bipod for one of them. We found these at the Rajma weapons storage facility base, and they had survived the aerial bombing of the base a few days earlier. I called a US Special Forces soldier [not this editor -Jack] I knew in the states to ask for basic advice about mortars. Our group in March had planned to use these mortars during the war, but never got the chance because of the ambush in Brega.

I never saw a P90 used during combat. The P90 I was photographed with was the only one I ever saw. It was in Sirte, but I never fired it, and never saw anyone fire it.

The Ajdabiya weapons service team were amazing. They had a large truck with an air compressor they used to clean weapons with a diesel fuel and compressed air spray. They and others made repairs and modifications to weapons that were essential to keeping them in service. They were some of the most brilliant and hardworking rebels in the war.”

You mentioned that there was a specialized cell that serviced weapons out on the front lines, were there any other specialty units, and did these units self organize organically or how did they come about?

“The weapons repair and service units appeared to have just gotten together on their own. The main one on the east side were a group from Ajdabiya city with a variety of backgrounds. They were mostly weapons cleaning and servicing. The more mechanic and serious weapons repair group were not from Ajdabiya I don’t think, but they also appeared to just develop organically. I don’t think either of these units were under the direction of the NTC or any katiba (brigade). They just showed up each day at a rally point behind the front lines and everyone knew where to find them. I stayed at the house they were using in Sirte a couple of times and got to know them fairly well. Without them the war would have been very difficult. They were indispensable.

Food and water supply was handled the same way it appeared. Trucks would just show up with plastic bags of food (mostly juice boxes, packaged sweet pastries, etc.), occasionally hot food in containers, and bottles of water. There were also the civilian volunteers who would bring pickup trucks near the front lines and serve us food, water, etc. out of the back of the truck.

There were also women making meals, which would then be brought to the front. Occasionally they would contain little pieces of paper with sayings in Arabic to encourage us. It was very inspiring.

It really was a war effort, and so many people got involved to support us. When there was a need people showed up to fill it. One time a truck showed up and delivered shoes (with KBR label on the boxes, not sure if it was THAT KBR or not, I have pictures and video) because some rebels didn’t have good shoes.

On the west side they had a snack bar with men serving coffee, making sandwiches, and once I saw them giving away packets of cigarettes. It was an organized operation. I think it was mostly intended to service the medics and journalists, but others ate there sometimes as well (including Nouri and I).

There wasn’t enough organization to really accomplish this in any other way than people stepping up to fill needs as they arose. It was an incredible thing to see.

I am not sure where exactly the food and water was coming from or who coordinated the supply lines. I was just glad they were there. Our commander gave Nouri and I control of the jeep to use as we saw fit, which meant that when our brigade was awaiting orders, etc., Nouri and I would go and fight alongside other brigades as well. This meant we had many engagements with the enemy, but being out on our own so much also meant that we didn’t spend as many days at our brigade’s base and weren’t around for meal times. I know that the brigades knew when and where the supplies would be and were well supplied, but Nouri and I were in a special situation since we often operated independently of the brigade, and since we were on our own and away from the brigade so often we ended up eating with other rebels or finding our own food.”

There is a still a lot of skepticism about the future of Libya, not to mention the Arab Spring in general, but what is your personal opinion about the future for democracy in this region?

“The region will have democracy. Islamists will win the first few elections because they’re already organized and will be better at playing politics than their secular opponents. The populations of recently liberated countries will tend to be more religious, as the violence, hardship, and loss during war tends to make people embrace religion more. As a result the Islamists will do well at the polls at first, which is actually a good thing. It is far better to have them integrated into the political process than outside of it where they’re more likely to use violence or subterfuge in seeking power. Once they realize that the new war is political and they can be victorious working peacefully within the system (and benefiting from the perks and corruption of it as well), they will embrace politics.

Given the pace of secularization worldwide (accelerated by access to the internet and Western popular culture), Islamists won’t dominate politics for more than a few election cycles. The youth of the Arab world want many of the same things that Western youth want (including the vices), and they have little desire to live under the thumb of Islamists. Additionally Islamists aren’t necessarily skilled at governance, and when they govern poorly they’ll be voted out of power.

But in the end, it is up to the people of these countries to decide their future at the ballot box. Beyond advocating for democracy and helping them to achieve it, it isn’t my place, or anyone else’s, to tell them who to elect or who not to elect. If they want to elect an Islamic government so be it, and we’re free to then interact diplomatically with that government however we see fit for our interests. Trying to influence politics in these countries is a very risky game that is unlikely to work, and might backfire.

Nothing can stop the Arab Spring, and it will spread to an Iranian Spring, African Spring, and Asian Spring. The 21st century will be the century of freedom. I am confident that there won’t be an authoritarian regime left in the world by the mid-21st century.”

A huge thank you to Matthew VanDyke for sharing his incredible story with us and educating us about what was really happening on the ground in Libya. I find that these boots on the ground accounts are particularly enlightening to all of us here in America who had the often dubious mainstream media to rely upon for information. You can find Matt at his

blog and freedom fighting, and also on

Twitter and

Facebook.

COMMENTS