Don’t miss out on Part One.

How do you defeat an insurgency?

How do you win over a people who has been treated as second-class citizens for centuries? Throughout history, many a politician and military officer have lost sleep over such questions. Yet a particular strategy seems to work—blend in with the population, gain their trust by concrete actions, and chances are that you’ll succeed.

Mao wrote that an insurgency must first retreat and gather forces, then build infrastructure and population trust, and finally counterattack. A shrewd counterinsurgency, thus, would aim to disrupt the transition between these phases, thereby strangling the insurgency in its infancy.

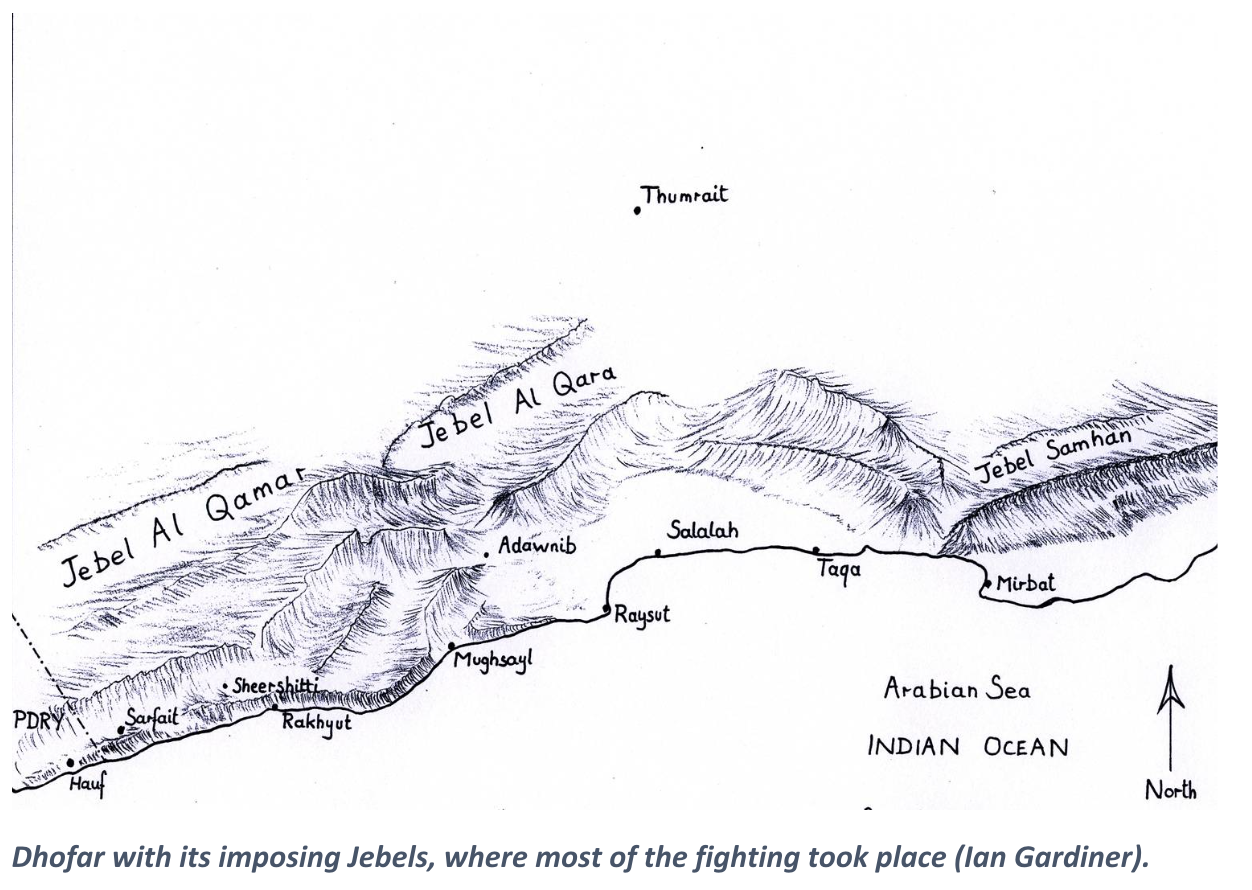

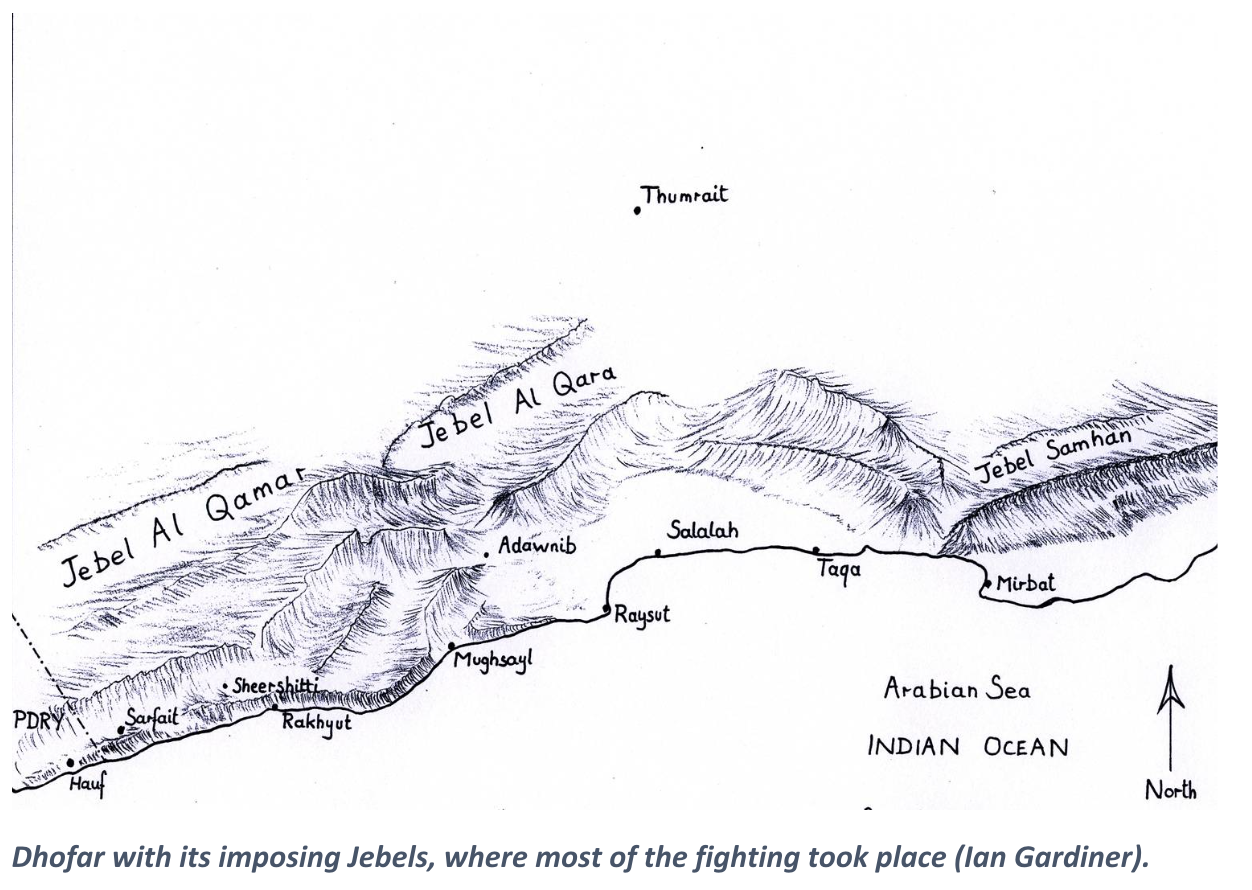

That’s exactly what the Sultan of Oman and his British allies sought to accomplish. The area of operations, Dhofar, was to be cleared, held, and developed. Enter the SAS. Oman wasn’t unfamiliar territory for Britain’s special operators. In the short Jebel Akhdar campaign of 1958, the SAS had been called to help the old Sultan against another revolt. In what was a typical SAS operation, two squadrons had scaled a precipitous mountain under the cover of darkness and surprised and overwhelmed the rebels in a short and violent battle.

Although the terrain, a combination of steep mountains, known as the Jebel, arid thorny scrub, deep wadis, which contained most of the region’s water supplies, and jungle, the result of the seasonal monsoons that run from mid-June through September, would be familiar, the enemy wouldn’t. This time around, they wouldn’t be fighting a few rogue tribesmen, but a well-disciplined, well-equipped communist insurgency that was operating from a haven, the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY).

Led by Major Tony Jeapes, an SAS Troop was dispatched in the summer of 1970. The British government’s horror of publicity restricted the number of the SAS to just twenty. They established their base at Um Al Gwarif. A few tents, an operations room, an armory, and a radio room were the only dwellings they could get away with.

To support the Sultan’s intent of modernizing the country and addressing, quite reasonable, the complaints of the Dhofaris, they formulated a four-part strategy. First, they would begin a hearts and minds campaign and get a civil development program going on the Jebel, Dhofar’s power center and wherefrom the adoo, literally meaning the enemy, was operating. Second, they would provide veterinary assistance to the villages—most of Dhofar’s economy rotated around livestock. Third, they would deliver much needed medical assistance to people who were suffering and dying from basic diseases. And finally, they would gather and analyze intelligence to support the Sultan’s Armed Forces; (SAF) operations.

As in most counterinsurgencies, holding ground was vital to the strategy’s success. The SAF and SAS had to get on the Jebel and stay there. Only then could the hearts and minds campaign bear fruits.

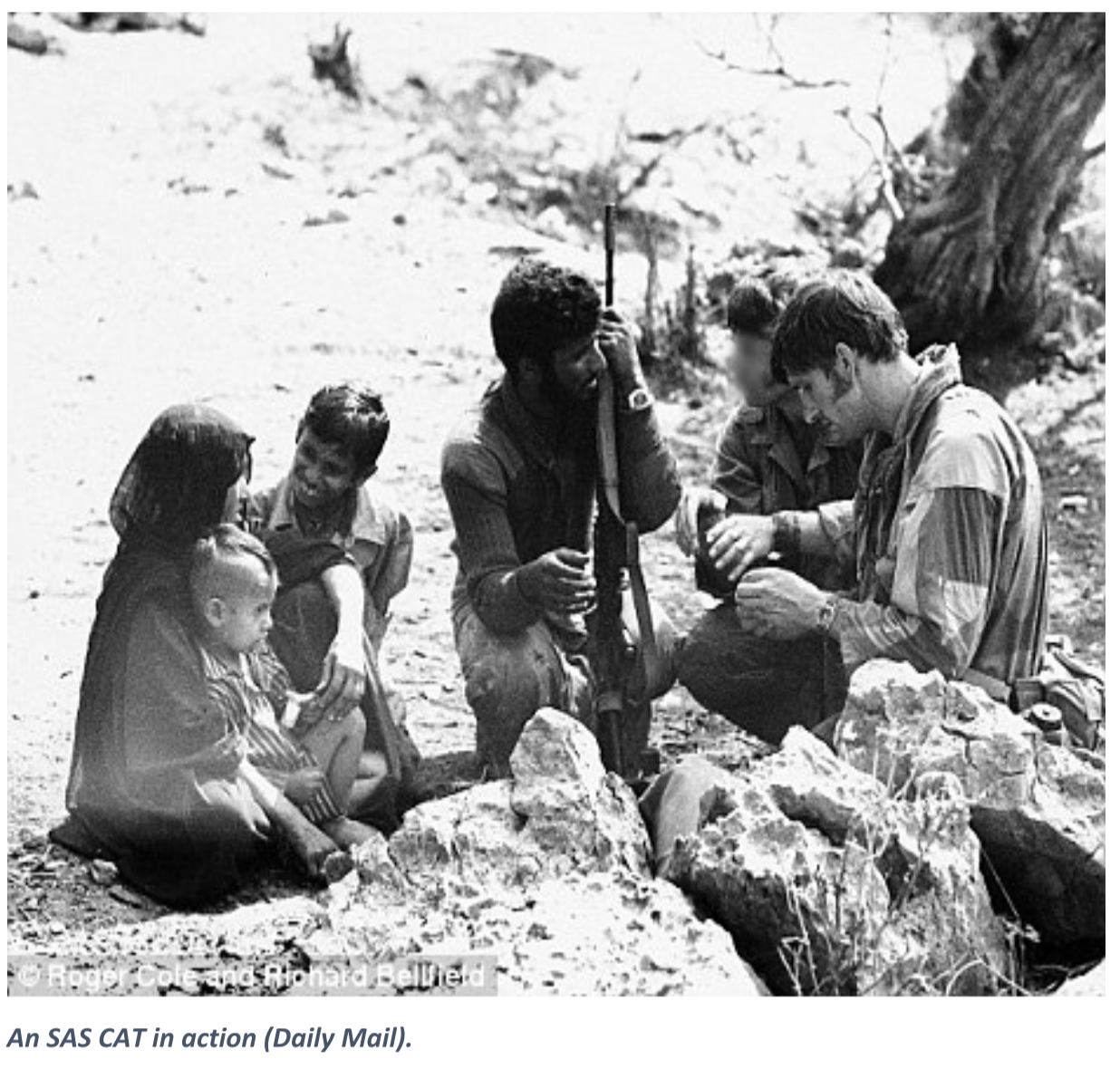

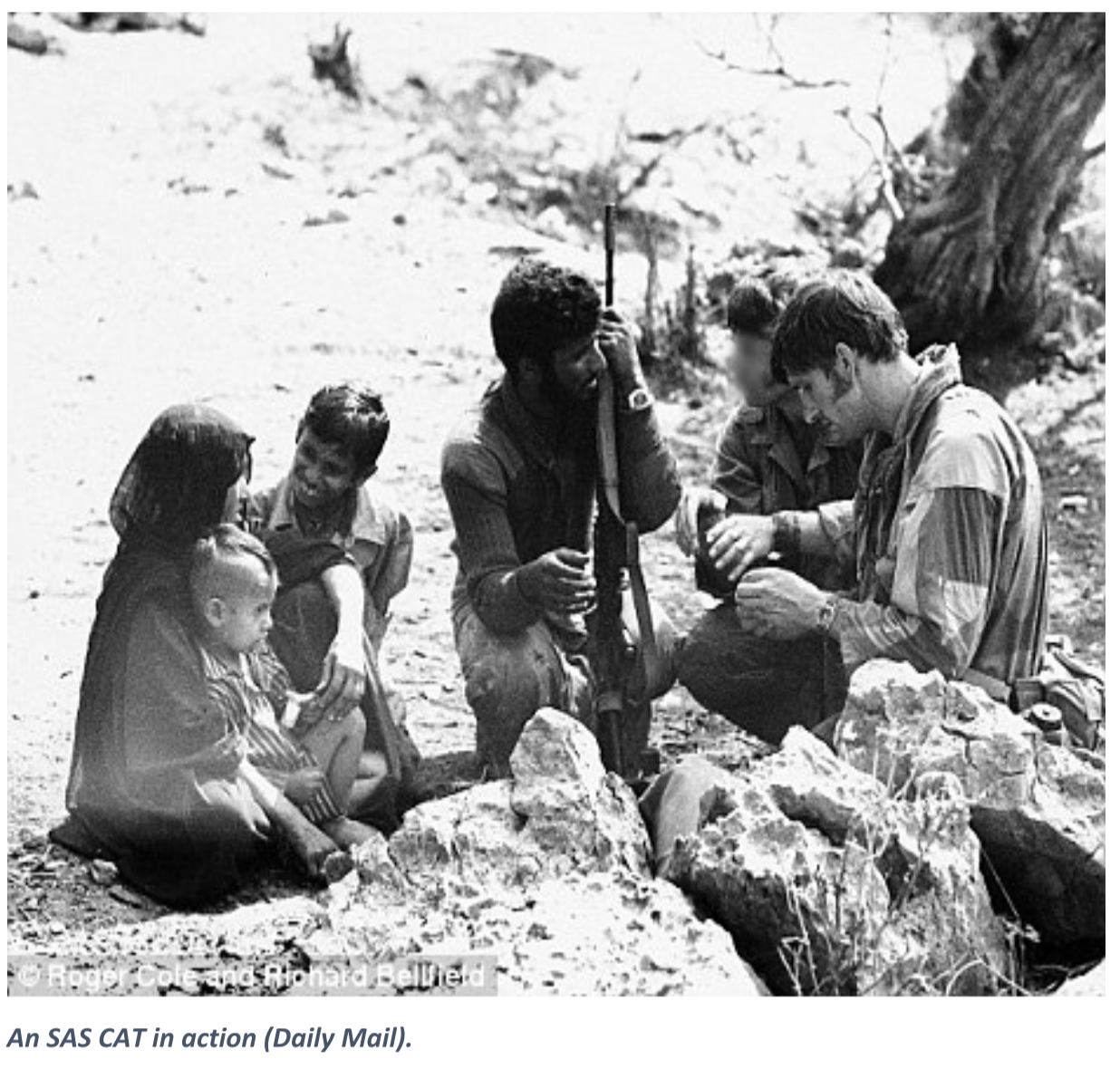

The SAS began by establishing four-man civil action teams (CATs). CAT Teams were composed of a leader, an Arab speaker, a signaler, and a medic. They came in the wake of the SAF and set up medical and veterinary shops in the villages. Attached regular British medical and veterinary officers complimented the SAS medics’ work. A flying doctor program was also established for emergencies and to reach the more secluded villages, of which there were many.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

They also supervised the drilling of new wells—a war-winning scheme in an extremely arid region that was only feasible by having a constant presence on the Jebel and the new technology introduced by the Sultan’s modernization commitment.

As the conflict progressed, they would gradually hand over authority to the Dhofar Development Department. An Omani face was always the goal. During their interactions with the Dhofaris, they would constantly encourage them to fight for the Sultan. Hearts and minds.

The CAT teams proved so effective that the adoo tried, unsuccessfully, to copy them. But danger always loomed. The first casualty came within a month of their arrival. Troopers had been cautioned to avoid unnecessary risks. Any publicity would cause the SAS’ withdrawal. Upon hearing that an SAS Trooper had been shot in a skirmish whilst clearing a village, the SAS commander thought otherwise; his expert medical opinion was that, “he had [just] fallen over a tent-peg and broken his arm.”

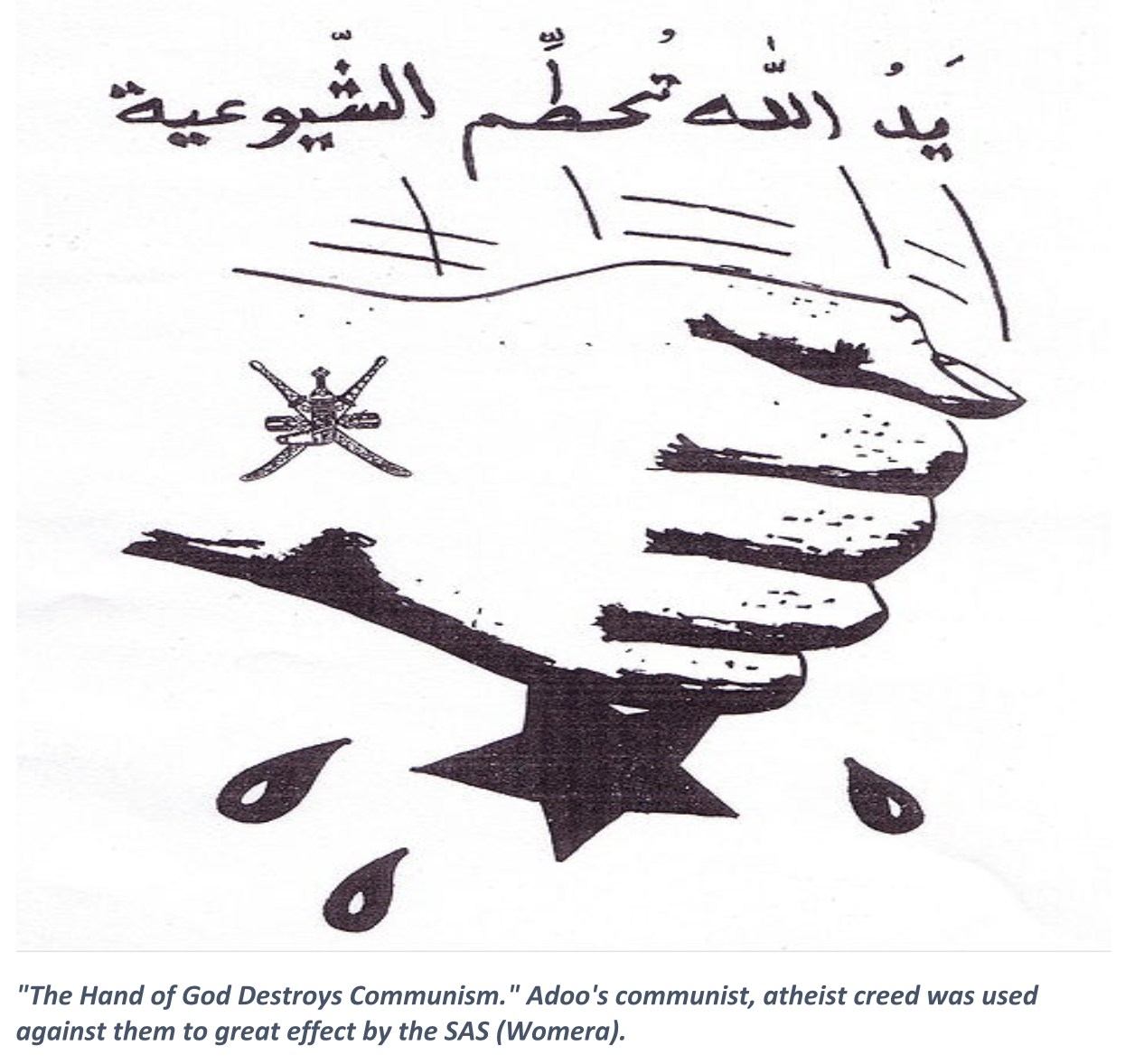

In conjunction with the CAT teams, the SAS also established an intelligence cell, which included an information team specializing in PSYOP. It was decided, however, that black propaganda wouldn’t be used. The main source of the adoo’s power and legitimacy came from the previous Sultans’ record of mismanagement and negligence. Thus far, they had used it amazingly effectively to bolster their support and discredit the new Sultan. Information, or at least the lack of, made their work that much easier. The SAS sought to counter that. A radio station was established, and cheap Japanese transistors were freely distributed around Dhofar so the people could listen to Radio Dhofar, the newly established government station.

The adoo responded by confiscating and destroying them. The SAS then came with a cunning plan: the next batch of transistors would cost a small amount—it should be noted that the Dhofaris are infamous for their avarice. So, when the adoo returned and destroyed the new transistors, they incited the population’s hostility. Hearts and minds.

The SAS also established news boards in each village and a regional newspaper. Arab-speaking troopers came up with an official logo for the whole information campaign: “Islam is our way, freedom is our aim.”

There was, however, the danger of Radio Aden, the communist propaganda mouthpiece. And up until the end of the conflict, a parallel war of information took place between Radio Dhofar and Radio Aden.

Gradually the civil development and PSYOPS campaigns bore fruits. From 1970 onwards, an increasing number of adoo deserted to the government side. This was doubly negative for the insurgency since they lost fighters whilst the government gained fighters. What’s more important, however, was the intelligence on supply routes, caches, tactics, and organization that they brought with them.

At first, the SAF and conventional British commanders were skeptical about these defectors. Could they be trusted? Could they be useful in any way? The SAS thought so. Enter the firqats.

COMMENTS