First Sergeant James Butler rode more than a mile on a very fast horse toward Reno’s forces to bring reinforcements before being overwhelmed and killed, while First Lieutenant James Calhoun, Captain Myles Keogh, and Captain Tom Custer each died in valiant, last stands of their own, hopelessly outnumbered by the determined enemy.

General Alfred H. Terry’s (Custer’s immediate commander) official report stated that Custer personally led Troops E and F down Medicine Tail Coulee toward the Indian village with about 90 men, boldly attacking across the Little Bighorn River, but “had unsuccessfully attempted to cross.”

This was later verified by the testimony of at least 15 Indian eyewitnesses, three of whom were Custer’s own Crow scouts, and two cavalrymen farther downstream, Privates Peter Thompson (Medal of Honor winner) and James Watson, all of whom saw Custer himself at the river. Conversely, there were absolutely zero battlefield witnesses who saw George Custer standing, or even alive, at any time after the failed river crossing.

Major Marcus Reno, an actual participant in the battle, accurately confirmed this incident just four years later, writing that, “We now know that Custer headed down to the river at Medicine Tail Coulee…(and) came face-to-face with 10 Sioux warriors (actually, four Cheyenne and six Sioux), all of whom fired on him…Custer, shot through the chest, was carried away on horseback by one of his men, and his brother, Tom Custer took command.”

Pretty Shield, age 20, the wife of Custer’s Crow scout, Goes Ahead, further confirmed that, “(Custer) went ahead, rode into the water of the Little Bighorn…and he died there, died in the water…the other blue soldiers ran back up the hill.”

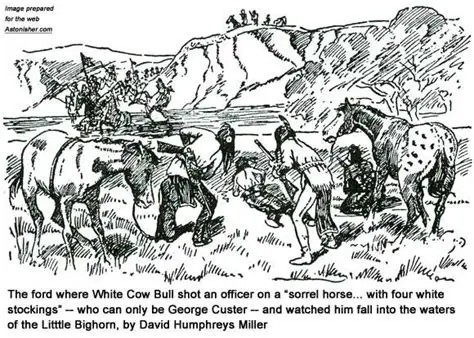

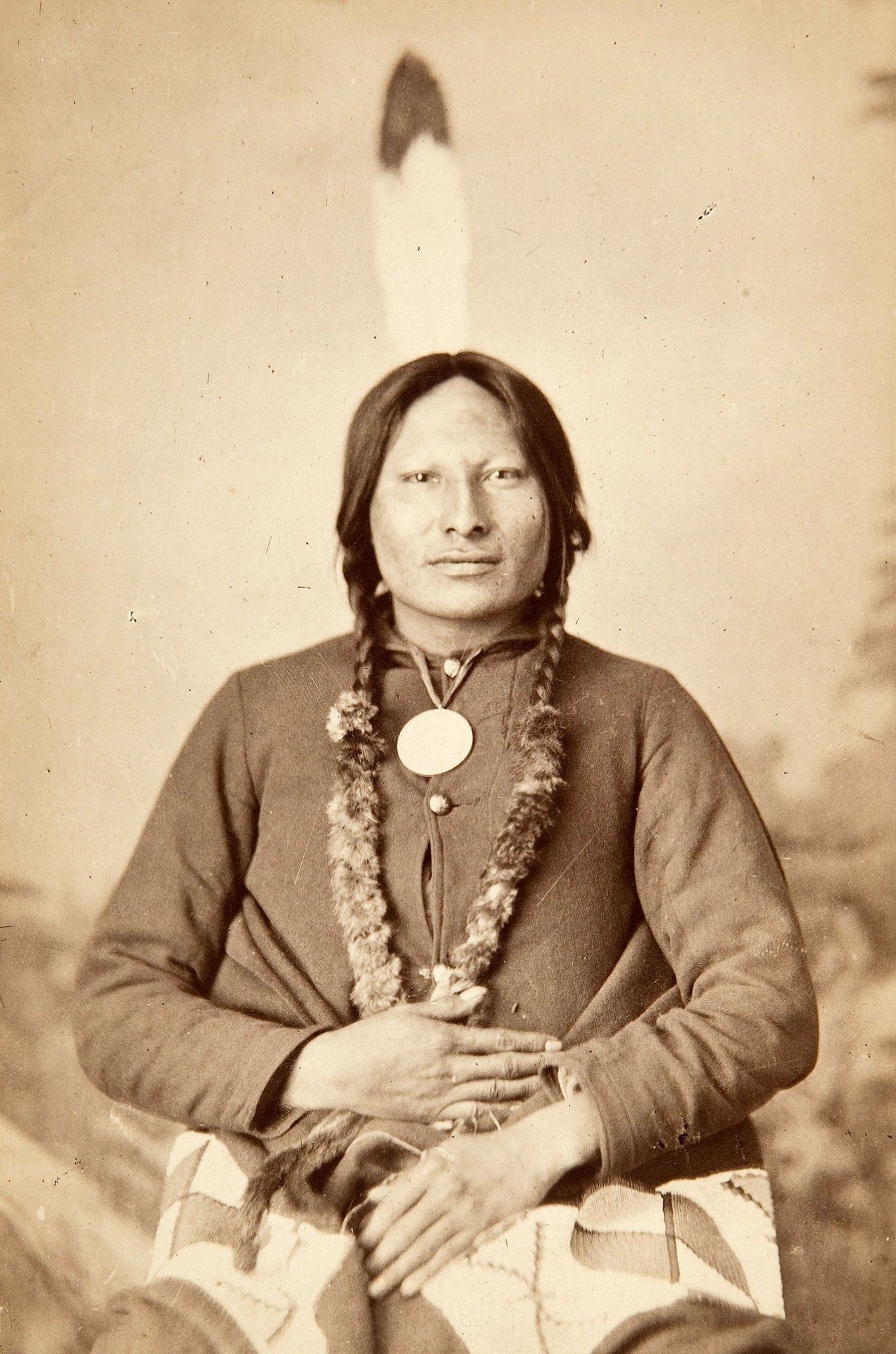

Indeed, White Cow Bull, aged 28, a Cheyenne Warrior, said that he killed or badly wounded an officer in buckskin clothing with a “big hat,” a “moustache,” and a “heavy rifle,” who was riding a “sorrel horse with…four white stockings.” This detailed, physical description perfectly matches only one cavalry officer and one horse on the entire battlefield, George Armstrong Custer and his Kentucky, thoroughbred, sorrel stallion, “Vic” (short for “Victory.”)

“The soldier chief was firing his heavy rifle fast. I aimed my repeater at him and fired. I saw him fall out of his saddle and hit the water.” At the end of the battle, White Cow Bull climbed Custer Hill and positively identified the body of officer that he shot. It was, indeed, George A. Custer.

Author David Humphreys Miller, who wrote “Custer’s Fall” in 1957, personally interviewed 72 Indian eyewitnesses to the battle between 1935 and 1955 in their own Lakota language, including White Cow Bull, age 91 in 1939, writing what was probably the best-researched book ever published about the Little Bighorn.

Miller described it this way: “Just then, at midstream, the unbelievable happened. Custer, the great, invincible, soldier-chief, golden-haired hero of the effete East, self-styled swashbuckler of the Plains, Son-of-the-Morning-Star to the Crows, Long Hair to the other tribes, fell, a hostile bullet through his left breast.”

Nathaniel Philbrick’s, “The Last Stand,” published in 2010, was glowingly described by the Los Angeles Times: “With strong, narrative skill, offering broad context and narrow detail, Philbrick…dismantles old myths, piece by piece.” He expertly concluded that George Custer was shot very early in the battle, that Tom Custer probably shot his mortally-wounded brother in the head at the last minute to prevent his capture alive by the Indians, and that Tom Custer was the last soldier to die.

More recently, Phillip Thomas Tucker, Ph.D., a noted Department of Defense historian, published “Death at the Little Bighorn” in January 2017, stating that, “A number of reliable and collaborating, Indian accounts…have revealed that (George) Custer was hit…while leading the charge across the ford.”

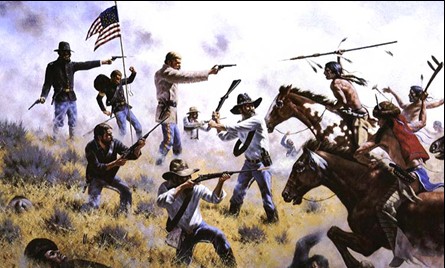

The overwhelming mountain of evidence clearly shows that George A. Custer bravely led the cavalry charge at Medicine Tail Coulee, but, as so often happens to soldiers at the very front of any formation in battle, he was, in fact, shot out of his saddle and mortally wounded in the chest, just below the heart, at approximately 4:21 PM, while in the middle of the Little Bighorn River.

As the rest of the regiment headed for the top of Custer Hill, First Lieutenant James Calhoun, George Custer’s brother-in-law, under Captain Keogh’s direct command, stopped and established a dismounted, skirmish line to hold back the Indians who were in hot pursuit. However, his troopers were soon overwhelmed by a flanking attack from Chief Crazy Horse and his Sioux warriors.

White Bull, age 26, a Minneconjou Sioux warrior riding with Crazy Horse, and the nephew of Sitting Bull, vividly described Calhoun’s last moments: “A tall, well-built soldier with yellow hair and moustache saw me coming…We grabbed each other and wrestled there in the dust and smoke…This soldier was very strong and brave…then grabbed my gun with both hands until I struck him again. But the tall soldier fought hard…He hit me with his fists…and tried to bite my nose off…I thought that soldier would kill me…Finally, I broke free. He drew his pistol. I wrenched it out of his hand and struck him with it three or four times on the head…shot him in the head, and fired at his heart…That was a fight, a hard fight.”

Uphill at this same moment, Myles Keogh saw the situation becoming increasingly desperate, and he apparently sent First Sergeant James Butler, known to have the fastest horse in the command, to the south, toward Major Reno’s command four miles away, to bring reinforcements and ammunition. But Butler only made it one mile before being savagely attacked by Cheyenne Chief Black Crane and warrior Red Robe, and dying heroically in hand-to-hand combat.

After the battle, Lieutenant Edward S. Godfrey stated, “Some of them may have been sent as couriers, by Custer. One of the first bodies I recognized and one of the nearest to the ford was that of Sergeant Butler…a soldier of many (16) years’ experience and of known courage. The indications were that he had sold his life dearly, for near and under him were found many empty cartridge-shells…I believe he had been selected as courier to communicate with Reno.” Indian chiefs, including Crazy Horse, later praised “the soldier with the braid on his arms” (a sergeant) as the bravest soldier in the battle.

Two days later, when the field was secured and the cavalry could assess the battle, Captain Myles Moylan and Lieutenant George D. Wallace found 28 shell casings beside Calhoun’s body. Moylan wrote, “There was no evidence of organized or sustained resistance on Custer field except around Calhoun.” One cavalry assessment said that 17 warriors were killed on Calhoun Hill, and that Lieutenant Calhoun and L Troop had made, perhaps, the stiffest resistance in the battle.

Later, Wooden Leg of the Northern Cheyenne said that “the last man killed” had “a big, strong body” and a “long, black moustache,” and was “down the hills, toward the river.” Two Moon added that, “One man rides up and down the line, shouting all the time…He was a brave man…He wore a buckskin shirt, and had long, black hair and moustache…He fought hard with a big knife.” This description exactly and exclusively matches that of Captain Myles Keogh, age 36, who was found with five dead Indian ponies around his position.

Keogh was the only cavalryman whose body was not mutilated at all after the battle, a clear indication of reverence and respect for his amazing courage. His famous bay horse, Comanche, was not killed or captured by the Indians for the same reasons, and was later found alive, literally the only surviving cavalry eyewitness to the battle at Custer Hill.

Sioux Chief Sitting Bull called Myles Keogh “the bravest of the brave,” and incredibly, when Sitting Bull was later killed by Indian police at the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890, he was wearing one of Myles Keogh’s Papal medals (the Pro Petri Sede, or Medal for the See of Saint Peter) around his neck as a talisman of extraordinary courage and sacrifice.

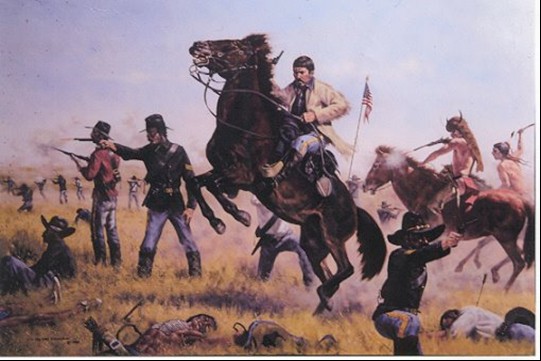

But, at almost exactly the same instant that Keogh was killed, at approximately 5:16 PM, another heroic captain in buckskins was about to meet his own fate. In 1881, Chief Red Horse of the Sioux told Colonel Garrick Mallory that, “Among the soldiers was an officer who rode a horse with four white feet (only George Custer’s personal horse, ‘Vic,’ met this physical description)…the last to die…the Sioux say this officer was the bravest man they had ever fought.

“I saw this officer in the fight many times…(He) wore a large-brimmed hat and a deerskin coat (matching Tom Custer’s description perfectly, and exclusively.) This officer saved the lives of many soldiers by turning his horse and covering the retreat.”

Wooden Leg noted that, “One wounded officer, a captain, still lived…He raised himself upon an elbow, glaring wildly at the Indians, who shrank from him, believing him returned from the spirit world. A Sioux warrior (probably Rain-in-the-Face) wrested the revolver from his nerveless hand and shot him through the head.”

Captain Frederick Benteen, an actual participant in the battle, cited for bravery, observed upon finding the bodies on Custer Hill that, “Only where General Custer was found was there evidence of a stand.” This was Tom Custer’s position as acting commander, and it was here that the Indians sustained their heaviest casualties. Two Eagles agreed: “The most stubborn stand the soldiers made was on Custer Hill.”

After George was seriously wounded at the river and carried to the top of the hill, Tom now had full access to George’s horse, Vic, and all of George’s weapons, giving Tom, a valiant, two-time, Medal of Honor winner, a total of two rifles, one of which was likely a rapid-fire, 15-shot, Winchester 1873 repeater, three fast-firing, double-action, Webley RIC .442 revolvers, two large knives, and perhaps the best and fastest steed (“Vic”) in the whole regiment. David Michlovitz concluded for Warfare History Network on August 27, 2015, that, “At the end, Tom fought like a demon possessed.”

Rain-in-the-Face, who had been captured, imprisoned, and beaten by Tom Custer in December 1874, before escaping in April 1875, was virtually the only Sioux warrior who actually recognized both of the Custer brothers on sight. At the very end of the Little Bighorn battle, he definitely attacked the top of Custer Hill and saw Tom Custer, known as Little Hair to the Indians, still alive. In 1894, he confessed that, “I saw Little Hair…He knew me. I laughed at him and yelled at him…I shot him with my revolver. My gun (rifle) was gone, I don’t know where…That’s all there is to tell.”

Then, in 1905, Rain-in-the-Face made a deathbed confession, “Yes, I killed him. I was so close that the powder from my gun (revolver) blackened his face.” The famous Sioux warrior admitted to using a revolver at the Little Bighorn, but was later photographed (about 1880 to 1883) in possession of a 1873 Winchester repeating rifle, serial number 487, manufactured in 1874, in .44-40, with the crooked, capital letter “C” crudely engraved on an oval, metal plate on the stock. It sold at auction for $132,000 in November 2018. Was this, in fact, Tom Custer’s gun?

Based upon a mountain of physical evidence and compelling, eyewitness testimony, on March 11, 2011, I officially and posthumously nominated Captains Tom Custer and Myles Keogh, as well as First Lieutenant James Calhoun and First Sergeant James Butler, for the Medal of Honor through formal, U.S. Army channels. Yet, over the next two years of back-and-forth correspondence, instead of earnestly cooperating, the Army inexplicably threw every possible impediment in my way.

The 1876 version of the Medal of Honor, according to the Army’s own written criteria, was for soldiers “as shall most distinguish themselves by their gallantry in action,” which was virtually the only requirement at that time. In 1876, there was no requirement for nomination through the military chain of command, no requirement for any testimony or witnesses, and no limit on the number of medals that could be awarded to each soldier. The four men that I nominated all certainly met this official standard.

It was readily apparent that in order for the Army to award these exalted medals, they would have to tell the truth about what really happened at the Little Bighorn, officially dispelling the enduring Custer Myth once and for all. In the end, they declined, not once but twice (in February 2012 and January 2013), and the revisionist, fantasy history of the Battle of the Little Bighorn is still the U.S. government’s final word on the subject, despite the incredible wealth of evidence to the contrary.

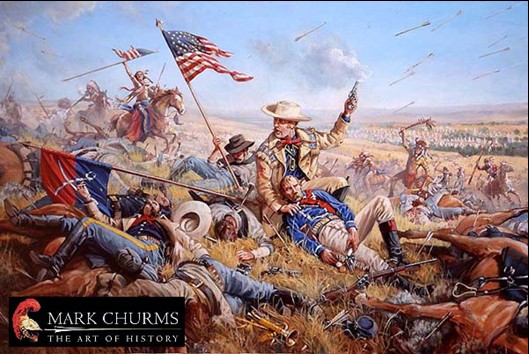

How will this nation honor and remember “the bravest man the Sioux ever fought,” and what does that say about us as Americans? Let’s take just a moment to honor the greatest, unrecognized hero of the Battle of the Little Bighorn by reading the official, proposed U.S. Army citation for Captain Tom Custer’s unprecedented third Medal of Honor nomination:

“After his regimental commander was mortally wounded, Captain Custer took command and relocated his five companies to higher ground in the face of an overwhelming, enemy onslaught. Encircled by well over 2,000 Sioux and Cheyenne warriors, he boldly issued orders for the defense of the regiment, assessed his commander’s medical condition, and fought heroically until the very end of the battle under a most-galling fire, most likely the last cavalryman to fall in action.

“As the best-armed soldier in the field that day, he inflicted the greatest volume of casualties upon the surrounding Indians, making by far the most fierce and stubborn, last stand on the entire battlefield, according to the sheer volume of empty shell casings near his body, cavalry after-action assessments, and the later admissions of enemy leaders. Indian warriors described him as ‘the bravest man…the last to die,’ courageously fighting to the very end, and rising up to fire one final shot before being killed in action while valiantly defending the regimental headquarters staff at the cost of his own life. Chief Red Horse vividly described Captain Custer as ‘the bravest man the Sioux ever fought.’”

COMMENTS