Years in Captivity

Wainwright’s ordeal began in the Philippines, where he was paraded by Japanese captors and then shipped north.

Over the next three years, he was moved between prison camps in Luzon, Formosa (Taiwan), and Manchuria. Conditions were brutal—beatings, malnutrition, disease, and psychological torment were daily realities.

Although isolated from his men, Wainwright shared their fate. He wasted away, losing weight and strength, and his once-lean frame became emaciated.

By 1945, the once vigorous cavalry officer was nearly unrecognizable, convinced that his country would judge him as the general who surrendered the Philippines.

Liberation at Last

In August 1945, Japan’s surrender brought the war to a close.

Russian forces advancing into Manchuria overran the camp where Wainwright was held, liberating him and thousands of other prisoners. The sight of freedom was almost overwhelming.

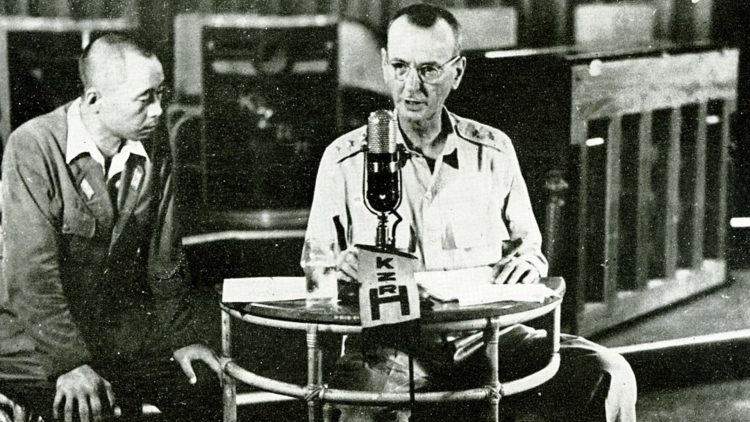

When he was flown to Yokohama, Japan, for the formal surrender ceremony, his former commander, MacArthur, was stunned at his physical condition.

Yet what Wainwright feared would be disgrace turned instead to admiration.

The American people saw in him not a failed commander but a man who had endured captivity with courage and shared the same hardships as his soldiers.

Medal of Honor and Legacy

Upon returning home, Wainwright received a hero’s welcome.

In September 1945, President Harry Truman presented him with the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor. His citation praised his “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity above and beyond the call of duty,” noting that his leadership had inspired his troops even in the darkest hours.

Wainwright was then promoted to full general and celebrated as a symbol of perseverance under impossible circumstances.

Below is an excerpt from Wainwright’s Medal of Honor citation:

“…At the repeated risk of life above and beyond the call of duty in his position, he frequented the firing line of his troops where his presence provided the example and incentive that helped make the gallant efforts of these men possible.”

Wainwright remained in uniform until retiring in 1947. Though his health never fully recovered from his years as a prisoner, he continued to embody the spirit of loyalty and sacrifice that defined his career.

He died in 1953, leaving behind a legacy that continues to inspire soldiers and historians alike.

Portraits of Jonathan M. Wainwright IV (Wikimedia Commons)

The story of Jonathan Wainwright is one of endurance and redemption. His surrender at Corregidor was a tactical defeat but a moral victory, demonstrating the limits of human endurance and the loyalty of a commander who chose to suffer with his men rather than escape. His liberation on August 23, 1945, marked not just the end of his captivity but the restoration of honor to a soldier who never abandoned his duty.

Today, Wainwright is remembered as a hero of the Philippines campaign and a Medal of Honor recipient whose legacy lives on in the history of the US Army. His story reminds us that true heroism is measured not by avoiding defeat but by facing it with courage, resilience, and devotion to those you lead.

COMMENTS