His first military engagement against the British occurred while Pulaski was still, in effect, a civilian. During the Battle of Brandywine, on September 1, 1777, the British were forcing the Continental Army back. Pulaski rode out into the battle with Washington’s 30-man security detachment.

Pulaski’s reconnaissance had shown that the British were trying to cut off the Colonials avenue of retreat. Washington, disregarding the regulations, told Pulaski to gather as many stragglers as possible, and allowing him absolute discretion in employing those troops, ordered him to cover the army’s retreat.

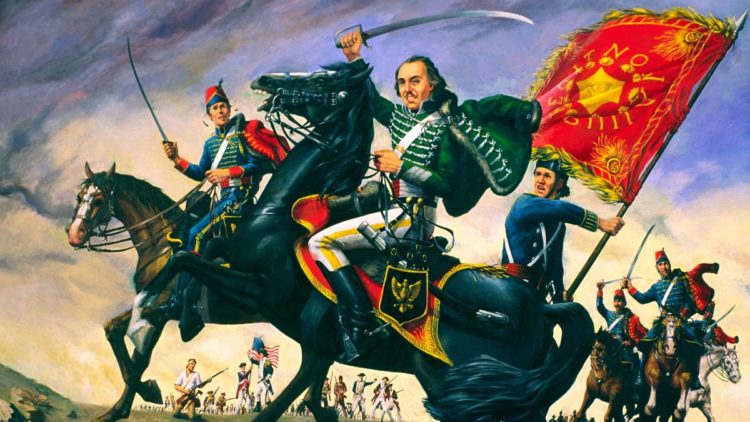

Due to his actions on the field, a potentially disastrous defeat was avoided and the life of General Washington was saved. Now, everyone knew who this Polish officer was. Finally on September 15, 1777, on the orders of Congress, Washington made Pulaski a brigadier general in the Continental Army cavalry.

The cavalry was tiny at the time but Pulaski and a few other Polish officers grew the unit and published the first regulations. During the winter at Valley Forge, Pulaski drilled the men and had them prepared to go. On operations in New Jersey at the request of General Anthony Wayne, Pulaski’s cavalry had the British convinced that the Continental cavalry was a much larger unit.

But many of the American officers greatly resented taking orders from a Polish officer who could barely speak their language. Despite being commended by Wayne, Pulaski resigned his commission.

Following his resignation, he went to Yorktown and met with General Horatio Gates. He proposed to him the creation of a unit that would be a mixture of Lancers and light infantry troops. Gates seconded his proposal to Congress which approved it. The unit would be called “Pulaski’s Cavalry Legion.” Pulaski was also reinstated as a brigadier general.

Pulaski often spent his own funds when money from Congress was late or not coming at all. However, some officers claimed that he had played loose with unit funds, a charge that would follow him to his death.

Pulaski considered resigning his commission and returning to Europe, but he decided to stay and was transferred to the Southern front by Washington.

In early May 1779, Pulaski arrived in Charleston just as the British were driving the militia back into the city. He led his men on what was later described as an ill-advised attack. His Legion suffered horrendous casualties and his infantry troops were nearly wiped out.

In September, he was ordered to Augusta and there he combined his forces with those of General Lachlan McIntosh. Pulaski’s troops captured the British fort near the Ogeechee River. His units then acted as a screening force for the allied French units under Admiral Charles Hector, Comte d’Estaing. He served with distinction during the siege of Savannah, and in the assault of October 9 commanded the whole cavalry, both French and American.

On October 9, 1779, Pulaski, while attempting to rally retreating French cavalry troops, was hit by grapeshot. He was evacuated to the ship USS Wasp where he died on October 11.

He was originally buried in an unmarked grave on the former plantation of William Bowen. In 1854, his bones were reinterred inside a marble monument. But nearly 200 years later, Pulaski was finally given the burial he deserved: In 1996, on the 226th anniversary of the battle that cost him his life, Pulaski was buried with full military honors under a 54-foot marble statue in Monterey Square in Savannah.

On that day, the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist held more than 700 people for a memorial Mass. Among them was Polish Undersecretary of State Andrzej Majkowski and Janusz Reiter, Poland’s ambassador to the U.S. A regiment of Polish cavalrymen on horseback escorted Pulaski’s casket in a procession through the streets of Savannah, followed by a riderless horse with empty boots in the stirrups.

COMMENTS