“In one room, where they [have] piled up twenty or thirty naked men, killed by starvation, George Patton would not even enter. He said that he would get sick if he did so. I made the visit deliberately in order to be in a position to give firsthand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations merely to ‘propaganda.'”

Through these efforts, Eisenhower hoped to preserve the bitter truth of the Holocaust and for future generations to come to be reminded that such atrocities happened and could possibly happen again if not prevented, as well as to honor those who have perished in misery, not just in Ohrdruf but in other Nazi concentration camps as well. It also ensures that alterations in history, on what exactly happened during the Holocaust, will not be forgotten or denied.

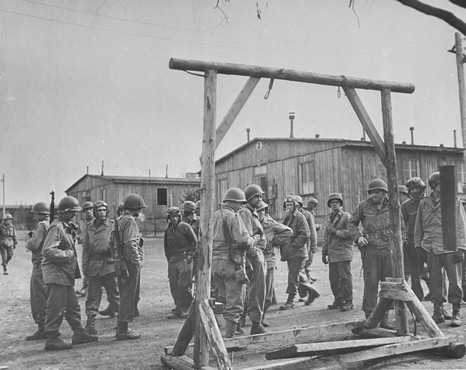

Crimes Committed in Ohrdruf

Located south of Gotha, in the Thuringia region of Germany, the Ohrdruf concentration camp was built in November 1944 as a Nazi German forced labor under the supervision of the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office (SS-WVHA). It later became a subcamp of the Buchenwald—one of the first and largest camps that housed suspected communists long before World War II began—supplying slaved workers for a railway construction leading to a proposed communication center. This wouldn’t see its operational, though, as the Americans were able to advance their forces and liberate the camp by April 1945.

As the war’s end loomed and the Germany Army found itself on the losing end, it began its evacuation of almost all of the prisoners—including prisoners of war, Jews, homosexuals, and more—forcing some 10,000 ill, sick, and starving individuals on a death march to Buchenwald. The SS guards punished those who couldn’t walk or were too weak to stand on their feet, and many ended up getting killed.

Just weeks later, the American forces arrived.

Aside from Eisenhower, General Patton also wrote his account of what he saw that day at the Ohrdruf, describing it as “one of the most appalling sights” he had ever seen. He recounted:

“In a shed . . . was a pile of about 40 completely naked human bodies in the last stages of emaciation. These bodies were lightly sprinkled with lime, not for the purposes of destroying them, but for the purpose of removing the stench.

When the shed was full—I presume its capacity to be about 200, the bodies were taken to a pit a mile from the camp where they were buried. The inmates claimed that 3,000 men, who had been either shot in the head or who had died of starvation, had been so buried since January 1.

When we began to approach with our troops, the Germans thought it expedient to remove the evidence of their crime. Therefore, they had some of the slaves exhume the bodies and place them on a mammoth griddle composed of 60-centimeter railway tracks laid on brick foundations. They poured pitch on the bodies and then built a fire of pinewood and coal under them. They were not very successful in their operations because there was a pile of human bones, skulls, charred torsos on or under the griddle, which must have accounted for many hundreds.”

Like many written reports before, the liberation of Ohrdruf and Eisenhower’s account of the horrors at the concentration camp opened the eyes of many Americans, both soldiers and civilians alike, to the inhumane conditions millions of innocent people faced during the rise of the Third Reich. The American troops would move on to liberate more camps, including Dora-Mittelbau, Dachau, Mauthausen, and eventually, Buchenwald.

Another account that tells us about the harsh condition in Ohrdruf was recorded by John W. Beckett, who served in the Third Army’s 734th Field Artillery Battalion. In his war diary, he wrote what he and his fellow soldiers witnessed at the camp and what they learned from a Polish prisoner who survived the atrocities of the SS guards. The same prisoner became their “tour guide,” showing them where they would be beaten, tortured, and executed.

“As the Polish prisoner talked, tears seemed to come to his eyes, but he fought them down,” Beckett recounted.

At the end of his chronicle, on April 17, 1945, Beckett described what he witnessed as something he thought would only exist in Roman times: “All such atrocities [sic] that were known to savages & Roman times & here it exists today in 1945, [h]ow is it possible, how can a man treat another as such. The question perhaps can’t be answered and I pray they will receive their just rewards, both here & in the life to come. Practically the whole battery went to see it & Patton wanted as many [of] his men that could go to see it & know that it is real & not propaganda. Its [sic] real, all too grotesquely real.”

Like Eisenhower, Beckett also emphasized how significant it is to keep the memories of the Holocaust, no matter how horrendous it was, alive and never be forgotten—for the sake of the victims and for the ghastly history never to repeat again.

COMMENTS