There is no hiding it now. Hundreds of miles above the Earth’s surface, in orbit, the US Space Based-Infrared System (SBIRS) missile warning satellite immediately detects the launch. If you’ve ever wondered, this is part of what Space Force does. SBIRS is one of our nation’s highest-priority space programs. According to its designer, Lockheed Martin, “the system includes a combination of satellites and hosted payloads in Geosynchronous Earth Orbit (GEO) and Highly Elliptical Orbit (HEO) and ground hardware and software.”

Space Delta Four

Information about the launch is almost instantaneously flashed to a military satellite in low Earth orbit, which relays the alert to the Second Space Warning Squadron (yes, that’s a real thing), which is part of Space Delta Four at Buckley Space Force Base in Aurora, Colorado.

Notice is sent to other Space Warning Squadrons and units comprising the Defense Support Program (DSP) and the commanders of all eleven Defense Department combatant commands. Not ten seconds have passed since the missile lifted off.

A second Space Force SBIRS satellite confirms the findings of the first and relays that information to the units noted above. This is the real deal. By now, the Hwasong-17 is traveling faster than the speed of sound and is punching a hole in the atmosphere. US satellites have locked on and started comparing the rocket’s thermal signature with hundreds in their database. It takes less than a second to confirm a match with the Hwasong-17 launches on March 24th and November 18th of this year.

The missile is now at 70,000 feet and climbing, about twice the cruising altitude of a commercial 747. Space Force has confirmed the launch, identified the type of missile, and relayed real-time information to the geographical combatant commands and US allies. A flash message is sent to the White House. They can’t be sure where the rocket is headed and may be tipped with a nuclear warhead.

According to Reuters, the missile launch last Friday (November 18th) flew a total distance of 621 miles over 69 minutes and terminated in waters west of Hokkaido Island, Japan. Some military analysts believe the North Koreans only tested one stage of the multistage rocket during its initial flights. They also think it was fired at a purposely steep angle to shorten the distance it traveled. The New York Times reports that if it had been launched at a more conventional angle for an ICBM, it would have been capable of reaching any part of the United States.

On Its Way to Space

As the main engine of the Hwasong-17 runs out of fuel, it shuts down. The missile continues on its way, going several thousand miles per hour when explosive charges separate the second stage from the first, and it’s on its way again. All this is going on about a minute and a half from launch time. The missile is now well on its way to exiting the Earth’s atmosphere. In Washington, the President of the United States is whisked down to the Situation Room, where he can have real-time communications with world leaders and the entirety of our military assets.

By now, Space Command has contacted South Korean and Japanese military forces and asked them to begin tracking the North Korean missile. In addition, SPY-1 radars on US ships in the Pacific are ordered to follow the missile’s trajectory, knowing the projectile is most vulnerable as it leaves the Earth’s atmosphere to enter space. Unfortunately, we can’t currently destroy a missile during this part of its flight. Our scientists are hard at work designing directed energy weapons that will one day solve this problem…but they are still years away.

Meet THAAD

I mentioned above that we didn’t have an effective means to knock the rocket out of the sky as it entered space, but we do have other tools to address incoming ballistic missiles. We have THAAD (Terminal High Altitude Area Defense) systems. They are designed to shoot down incoming ballistic missiles in their terminal, or descent, phase. They have no explosive warheads but rely on kinetic energy to knock missiles out of the sky. THAAD units in Hawaii, South Korea, and Guam would be activated in our hypothetical attack scenario. These systems have a pretty good track record but can only protect their assigned areas due to their limited range. Since our missile is headed for the continental United States, THAAD can’t help us.

To keep track of the timeline here, the above occurred slightly over two minutes after the Hwasong was launched. So it’s taken you longer than that to read this far.

Patriot missile batteries in the Pacific are called to alert. Like THAAD, these can only defend specific locations and lack long-range capabilities. Aegis-guided missile cruisers in the region are put on alert as well. Their RIM-161 standard missiles are intended to intercept short and medium-range ballistic missiles. Each has a range of several hundred miles, and they begin to scan their sectors for threats, just in case.

US Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) at Peterson AFB in Colorado coordinates with NORAD (North American Aerospace Defense Command) to activate homeland defense missile systems. As part of that effort, the GBI (ground-based interceptor) missile component of the GMD (ground-based midcourse defense) system is activated at Fort Greely, Alaska, and Vandenberg SFB in California. These missiles cover a far greater area than THAAD or Patriot missiles and are designed to destroy incoming enemy projectiles before re-entering the Earth’s atmosphere. Still, we don’t know the exact target of the North Korean weapon, so we continue to track every second of its flight. We watch and wait.

Flying Past Asia

Based on its speed, time in flight, and trajectory, US forces have ruled out targets in Asia. This missile is headed over the Pacific ocean at a high rate of speed. Focus shifts to Hawaii and the American west coast. Three minutes have elapsed since the launch. All past tests of the Hwasong series of missiles have terminated in Asia, so we have a solid reason to believe this may be an actual attack. We know the missile has the range to reach targets on the east coast of the US potentially, but targets on the west coast are a more likely destination because they can be hit with greater accuracy. Because of this, naval vessels with anti-ballistic missile capabilities are ordered to guard the most likely US targets on the west coast and Hawaii.

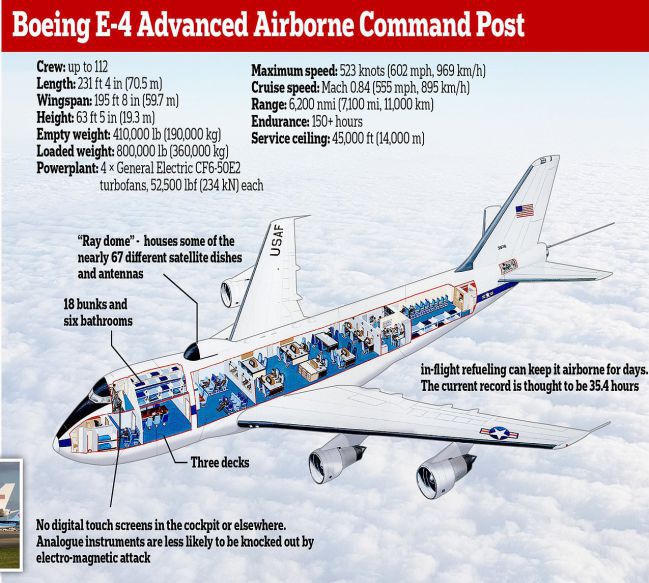

“Doomsday” planes (or Nighthawks) are ordered into the skies. These are more accurately referred to as Boeing E-4B Advanced Airborne Command Posts. The US maintains four of these aircraft as leftovers from the Cold War era and are jam-packed with the most sophisticated electronics and communications equipment we have.

The Nighthawks are intended to keep the lines of communication open during a worst-case scenario and allow the President and Joint Chiefs to keep talking to the combatant commands on the ground. They will remain in flight until the crisis is over.

All of our offensive nuclear forces are put on high alert. It is conceivable that another hostile nuclear power might use an attack on the United States as cover for “piling on” and launching their nukes. This is no time to let our guard down. The full might of our nuclear forces stands at the ready. This process includes prepping nuclear-capable aircraft and submarines for missions and readying their weapons for launch.

It’s roughly T+ five minutes since the missile left North Korean soil. The second stage of the Hwasong-17 is discarded and falls away. The remainder of the rocket containing the warhead is unpowered and uses chemical thrusters to adjust its trajectory. It has gained so much momentum that it travels at a rate of over 4 miles per second. Space Command has confirmed the separation of the stages and anxiously monitors the projectile.

Because of the projectile’s position and speed, Hawaii is ruled out as a target; it appears to be heading for the extreme southwestern United States. Missile defense personnel quickly decide to launch ground-based interceptor missiles from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California. Four missiles are activated and provided with live targeting data. However, launching is too soon as the incoming missile is too far from them to be effective.

Nuclear Football

At T+, six minutes after launch, the President of the United States, out of an abundance of caution, leaves the White House and boards a waiting Marine One. With him are Secret Service agents, a man carrying the “nuclear football” (aka the remote nuclear command authority unit), and an agent carrying a large backpack crammed with communications equipment to ensure the President never has a break in communications. He is flown to Joint Base Andrews, where he boards Air Force One. When airborne, all aboard should be protected from the effects of a nuclear blast.

Here is where Special Operation Forces (SOF) come into play: US and South Korean Special Forces located in South Korea and Japan are recalled and briefed on a probable mission involving North Korea. This mission has been planned for years, infiltrating and neutralizing North Korean nuclear weapons sites. We want to do all we can to prevent the launching of additional missiles. US and South Korean fighters and bombers take to the skies in preparation to support a possible attack from the North on the South. F-15s and F-16s will be sent up first to establish air superiority.

Conventional ground forces are given orders to prepare for combat. North Korea has so much artillery pointed south from positions north of the DMZ that they could initially rain down ten thousand rounds per minute on Seoul. Sirens throughout the city of ten million sound to warn citizens to seek shelter.

Back in the United States, data on the incoming ballistic missile continues to be tracked, and computers continuously work on firing solutions for the GBI.

Video of a test flight of the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense’s (GMD) Ground-Based Interceptor (GBI) upgraded booster vehicle. Courtesy of YouTube and Missile Defense Advocacy Alliance.

When the time is right, four ground-based interceptors are launched into the California sky. TPY-2 (aka Foward Based X-Band Transportable) radar tracks their flight. This system has a range of 2,900 miles and can be used to track, classify and intercept ballistic missiles. It has two operating modes: one is to locate and identify the threat, and the second (that we’re looking at today) is to guide interceptors into a descending warhead.

Target: Los Angeles

The US interceptors are in space in minutes, speeding toward the incoming projectile. The North Korean ICBM has been in flight for thirteen minutes now, and US forces have concluded that, without a doubt, its target is the city of Los Angeles. But, then, the single projectile suddenly fragments into eight individual warheads as it releases a burst of metallic chaff in an attempt to confuse American radar. We’ve long postulated whether the Hwasong-17 payload contained multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRV), and now we know for sure. Each of the eight warheads could possess a nuclear weapon, but chances are some or most of them are decoys intended to give the actual weapons a greater chance of hitting its target, LA.

This is where TPY-2 radar can either save the day or let us down. As our intercept missiles continue to speed to their targets, the radar system is constantly feeding data to supercomputers trying desperately to sort out the dummy warheads and trash from the real deal and send the GBI toward the live warhead(s). By now, you’ve figured out why we sent up four GBI, in case the first three miss.

Fortunately, the North Koreans have not perfected a means to have the dummy warheads give off the same signature as a live warhead, and our computers guide the interceptors to what they believe is the real thing. Fifteen minutes have passed since the missile took off half a world away. Now that the GBIs have a good firing solution, they detach their awesomely named exo-atmospheric kill vehicles (EKV). In seconds the EKVs are closing on their targets at over 4,000 miles per hour. We can do nothing at this point except wait and hope they don’t miss.

This footage from the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) has been approved for public release. It shows an exo-atmospheric kill vehicle intercepting and destroying its target in a direct collision. It also offers multiple views of an intercontinental ballistic missile target being destroyed via kinetic energy—video courtesy of YouTube, the MDA, and Leah Garton.

In our hypothetical attack, the first two EKV scream by the warhead, leaving it unharmed. The third hits home with a combined impact speed of over 10,000 miles per hour, smashing the warhead into thousands of small, harmless fragments. The interceptor does not have an explosive warhead and cannot set off a nuclear explosion. TPY-2 radar confirms a good kill, and everyone breathes a huge sigh of relief. The dummy warheads burn up in the atmosphere, and the good people of Los Angeles never knew how close they came to being part of ground zero.

Sources: The author would like to thank the wonderfully creative people at The Infographics Show for coming up with this idea of minute-by-minute tracking of a nuclear weapon launched by North Korea against the United States. They have provided much of the inspiration and source material for this piece.

COMMENTS