It was a success.

It revealed, however, some problems. A few troopers judged unsuitable and undisciplined for the quirks of jungle operations went home.

The Scouts next task was to recce the jungle and discover CT camps, caches, and trails. Launching from small comms bases within the jungle, four-man recce teams scoured the jungle for information to radio back.

Conditions were harsh. “Every sense was switched on to maximum,” ‘Lofty’ Large, a legendary figure within the SAS who fought in Korea, Malaya, Oman, Borneo, and Aden, remembered. “You listened, smelled, looked for everything. You got a feel for the jungle. A new sense of danger.”

But HQ was pleased. Which meant more money and men.

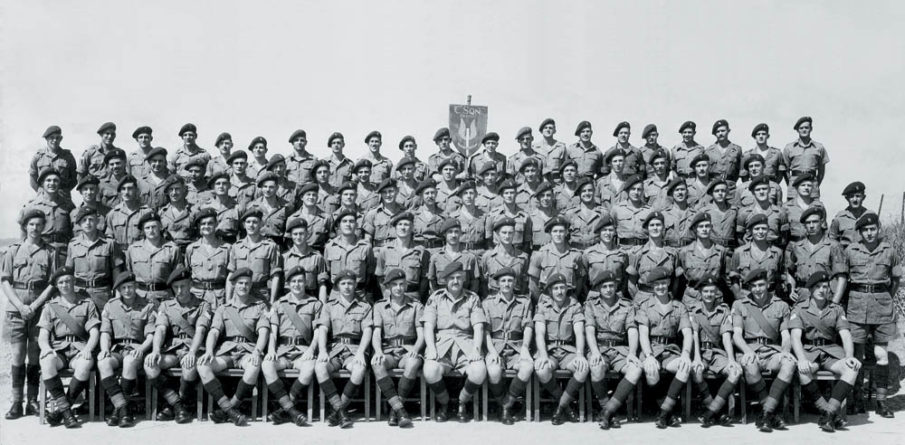

The newly formed B Squadron found its men in the territorials of 21 SAS. It was a distinct culture since most of the troopers had fought alongside in WWII.

C Squadron was only for Rhodesians. A hundred men, among them Ron Reid Daly, the father of the Selous Scouts, and Peter Walls, future CO of Rhodesia’s military during the Bush war, came from Africa.

By the end of 1951, the comeback was official. With three Squadrons, an HQ battalion, and Lt. Col. John Sloane as their new CO, the 22 Special Air Service Regiment was back.

From their new base at Sungai Besi, Sloane first resolved to reaffirm discipline and standards, which, despite the unit’s successes, were fledgling due to disease and fatigue.

Hitherto, there hadn’t been a time limit to patrols, causing burnouts among the ranks (one patrol went for 103 days, and another lasted 122).

Disciplined men would enter the jungle, but barefoot, pale ghosts with rotting uniforms would exit it. Troopers shed 1lb daily whilst on patrol.

Malaria, dysentery, leeches, and heat exhaustion plagued the ranks. “The Scorpions,” as one trooper recalled, “had somewhere to crawl under. But the leeches were right next to your ear. It was good!”

Sloane acted. Forthwith, patrols would be limited to fourteen days. New ration packs, dehydrated and bulked with rice and nuts (high in calories), appeared.

But difficulties kept arising. Maps, for example, were scant and inaccurate. “They were air photographs,” ‘Lofty’ Large recalled, “so they were taken from twenty, thirty thousand feet, and sometimes there was a cloud. So, on your map, you’d get a big white patch with the word cloud wrote on it. And that could cover fifty map squares.”

With enemy encounters being close affairs, each trooper wore different a colored bandana to distinguish his comrades in the ocean of green they sailed into.

Olive drab uniforms, sturdy, canvas Bergens, and leather jungle boots became standard. Boonies and berets offered shelter from the oppressive heat and bugs. Machetes and hatchets led the way.

If a river stood between a patrol and its path, ropes were used to create bridges. Rubber dinghies served for river rafting.

Patrols were often resupplied with mules, and some unfortunate troopers were designated as the mulemen (sadly with no extra pay!).

As for weapons, their choices were certainly many and colorful. The Australian Owen, and the British Sten, and Sterling sub-machine guns were favored for their compact, light nature. The FN FAL, AR-15, M16, M1 Garand, and Lee Enfield No. 5, a shortened version of the venerable No. 4, packed more punch. In case needed, Bren light and GPMG heavy machine guns offered firepower, and a shotgun per patrol became customary for its force.

Their humid and rotting hunting ground meant that weapons had to be cleaned and oiled constantly.

Effectiveness, morale, and discipline improved.

But the strain wouldn’t ever vanish.

And yet the future brimmed with excitement and potential: Hearts-and-minds missions with cannibal tribes, tree-abseiling parachute jumps, and the New Zealanders were coming next!

This article was originally published in April 2020.

COMMENTS