Lindberg has set the mouse trap, and now he waits.

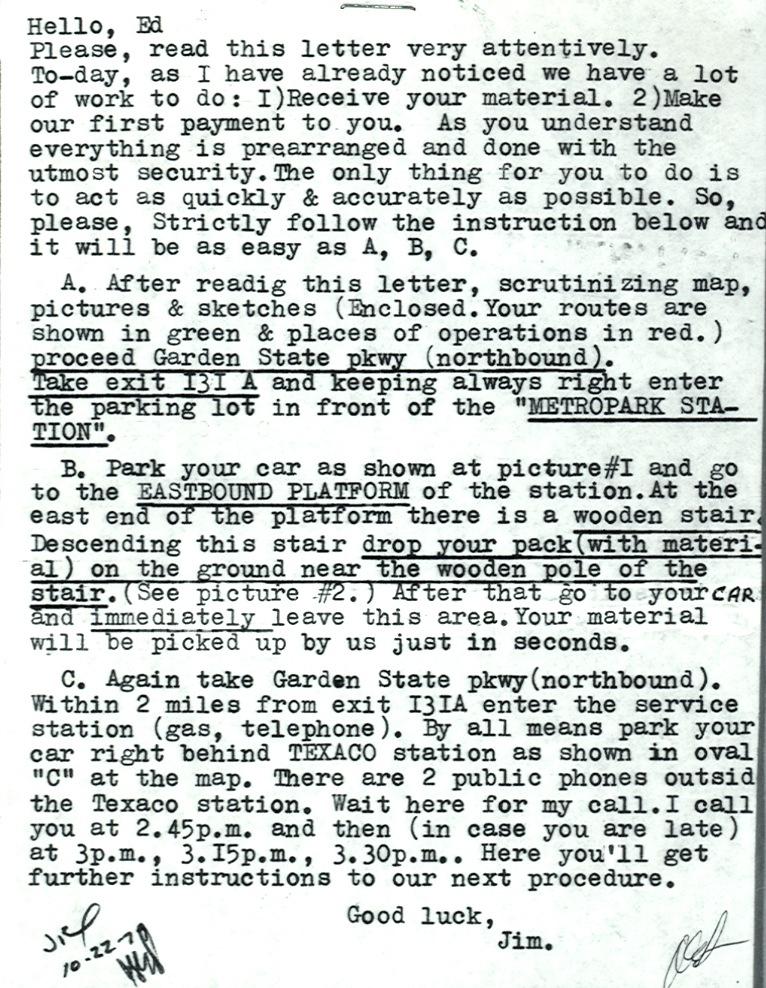

It didn’t take long, though, as he was shortly contacted by a Soviet agent, who gave him instructions via phone call and through a letter that the double agent would later receive. Accordingly, Lindberg would have to gather classified information regarding US antisubmarine warfare program, strictly follow routes to drop sites, and where his payment would be located.

For the succeeding months, Lindberg would feed the Soviets with “declassified” information while familiarizing himself with the espionage organization’s tradecraft and the intelligence agencies closely monitoring the drop zones near a major New Jersey crossroad. The double agent would also turn over all the Soviet letters and money, as well as the containers used in the exchange.

When both US agencies had gathered enough evidence, they instructed Lindberg to prepare for the final transaction in the late summer of 1978 that would become the final nail to the coffin for the Soviet spies.

Catching Them Red-handed

For months, Lindberg has been handing the spies declassified files, but on the day of the arrest, he gave them the real deal—classified materials that included “underwater acoustics, submarine detection systems, […] the LAMPS helicopter system, and other classified Navy materials,” that would cement a strong case once the Soviet spies would be caught red-handed.

A quick tangent. The Navy’s LAMPS program, or light airborne multipurpose system, sought to enhance the radar range and electronic interception equipment for antisubmarine detection. This led to the development of helicopters earmarked to assist the surface fleet in antisubmarine warfare. This led to the creation of the now-retired SH-2F Seasprite’s LAMPS Mk I, SH-60B Seahawk’s LAMPS Mk III, and MH-60R Seahawk’s LAMPS Mk III Block II (upgrade).

Having to identify and verify the drop zones, the FBI agents apprehended two Soviet employees of the UN Secretariat, Valdik A. Enger, And Rudolf P. Chernyayev, on the 20th of May, 1978, in New Jersey.

Enger and Chernyayev would be the first Soviet officials to face espionage charges in the United States.

Later, a third co-conspirator was briefly detained, Vladimir P. Zinyakin, a third secretary at the Soviet Mission to the UN. However, unlike the two previously mentioned men, Zinyakin would eventually evade arrest altogether due to his diplomatic immunity.

The New York Times 1978 report on the arrest and arraignment of the two KGB agents noted:

“Mr. Enger and Mr. Chernyayev were arraigned this (20 May 1978) evening before William J. Hunt, the United States magistrate in the Federal courthouse in Newark, about five hours after their arrest at 2 PM near the intersection of Woodbridge Center Road and Highview Road.”

At some point, during the hearing of Enger and Chernyayev, three Soviet officials had dramatically appeared in the courtroom and demanded to stop the proceedings as the arrest was illegal under international conventions.

The Aftermath

Nonetheless, Enger and Chernyayev were convicted and sentenced to 50 years in prison but would later be released in return for the freedom of five dissidents. Moreover, Zinyakin would be deported off US soil.

Throughout Operation Lemonade, Lindberg collected a total of $16,000 (about $73,825.77 in 2023 dollars) from the Soviet spies in exchange for top-secret files from the Navy. For his meritorious contribution to the operation’s success, the Navy official receives the Legion of Merit.

The FBI later told reporters additional details regarding the investigation, disclosing that the covert operations of the Soviet spies picked up “sketches, photographs, photographic negatives, plans, documents, writing, notes, and information” from at least seven prior drop locations beginning the 22nd of October 22, 1977.

Operation Lemonade did not only prove the suspicious activities happening at the Soviet’s UN headquarters, but it also provided US intelligence agencies a learning curve—an insight, filling in the pages of its guidebook on how the KGB and other foreign security agencies conducted their espionage operations during this period across the state.

“The Soviets repeatedly passed messages and money to Lindberg in the most ordinary, everyday items: magnetic key holders placed in phone booths, cigarette packs, soda cans, orange juice cartons, even rubber hose from an appliance. Most of the pre-arranged ‘dead drop’ sites where the secrets were supposed to be passed were along the busy New Jersey Turnpike.” via The New York Times, 1978

This, however, was just one of the many operations to come as a result of the cat-and-mouse game between the US and USSR during the Cold War.

Nonetheless, considering that the espionage case of Enger and Chernyayev was the first-ever, news about the arrest and arraignment spread like wildfire across the state and eventually reached the international community. The extensive publicity ultimately pushed the Soviet Union to release more than 200,000 dissidents from brutal Russian Gulags, also infamously known as labor camps for political prisoners and criminals, which housed millions of people at its peak.

—

For in-depth reading, check out The Unlikely Spy: The true story of “Operation Lemonade” and the Capture of Soviet Spies, written by Lindberg, the double agent himself.

COMMENTS