While the Vietnam conflict was in full swing, not too far away another war of similar nature was taking place. Although the Dhofar War (1963-1976) didn’t attract the same publicity as its infamous American contemporary, it was certainly no less — and probably even more — important for the global power balance.

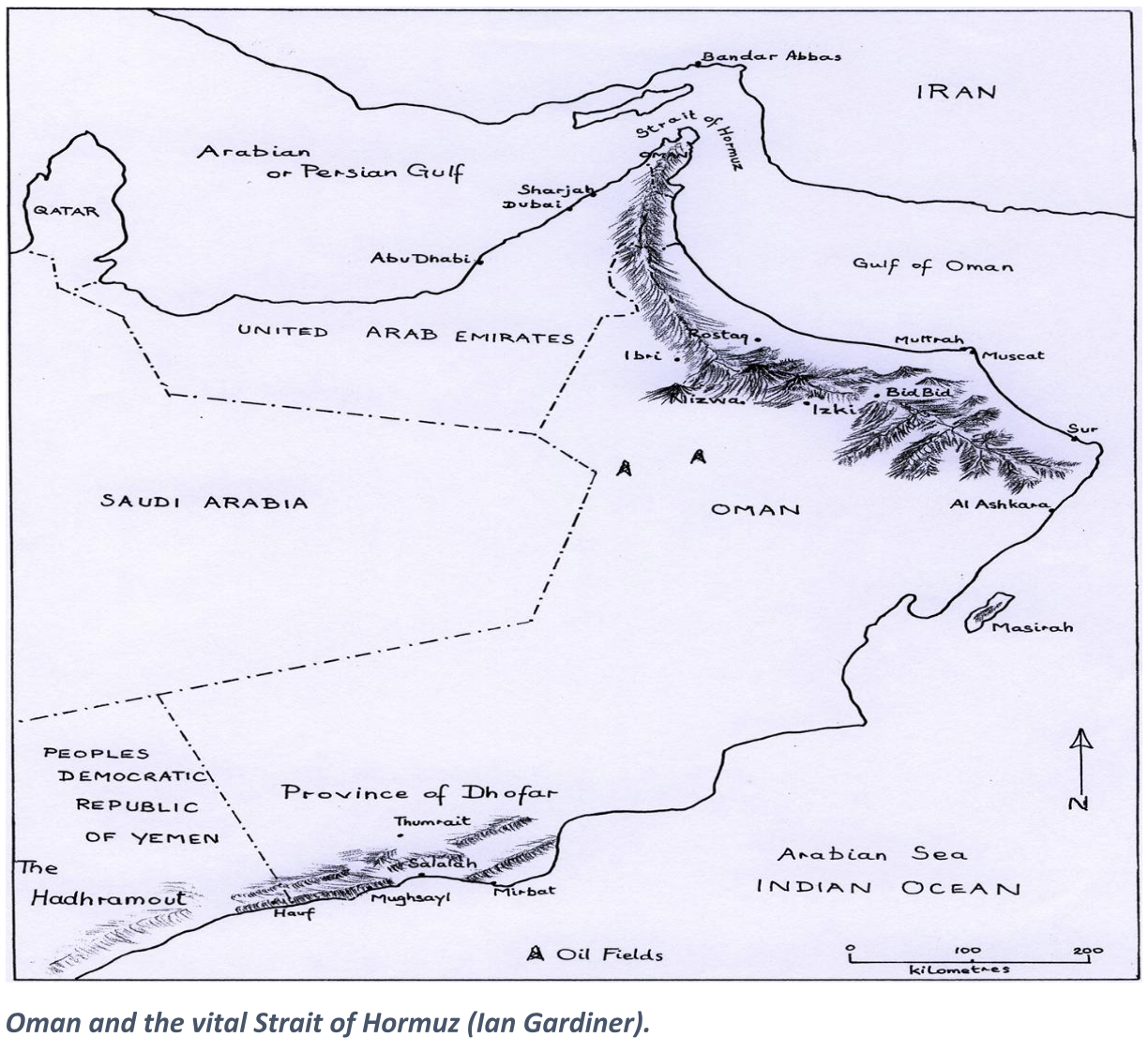

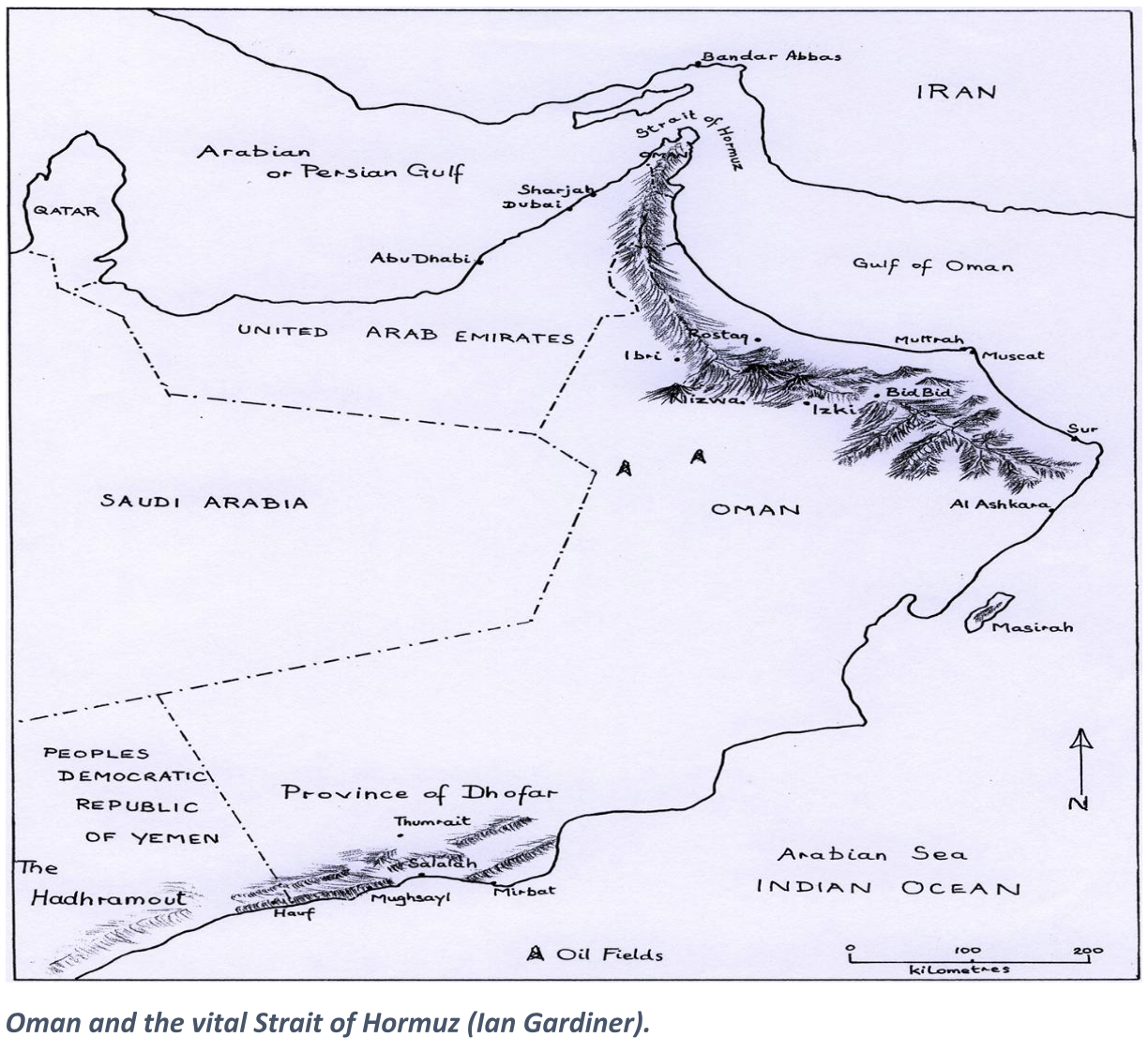

Whereas a terror of falling dominos provoked America’s spirited commitment in Southeast Asia, the safety of the Strait of Hormuz, the oil lifeline of the Western economy, triggered that of Britain in Oman. Indeed, the deserts, mountains, and scrub of Oman were a Cold War battlefield of no less significance than the hills of Korea, the jungles Vietnam, or the bush of Sub-Saharan Africa. The fight for material and ideological gains between East and West was bitter and prolonged.

The peculiar nature of the war saw British, Omani, Pakistani, Indian, Jordanian, Baluchi, and Iranian soldiers (the Shah was still in power) fighting together against the communist insurgents. The Popular Front for the Liberation of the Occupied Arabian Gulf (PFLOAG), in return, received training and arms from South Yemen, the Soviet bloc, Iraq, China, and Egypt.

From a troop number point of view, the war was small: a few thousand allied troops pitted against a couple of thousand communist insurgents. Such numbers, however, shouldn’t fool us about the conflict’s intensity and significance.

As already hinted, geography dictated importance. The Strait of Hormuz, where one-fifth of the world’s oil supply passes through daily, skirts the Omani coast. This shipping lane, 21 miles at its narrowest point, is the world’s most valuable petroleum sea passage and a strategic chokepoint. If Oman had succumbed to Communism, the West’s oil supply would’ve been in jeopardy and the world could’ve been a very different place today. (The Iranian revolution of 1978, which toppled the Shah, further increased the paramountcy of a free Oman.)

And why Britain?

Well, it was Oman’s colonial legacy that brought British intervention. Since 1798, a treaty of friendship existed between the Sultan and the British government. And during the centuries, British friendship had often materialized in the form of arms and troops.

Throughout the decade of British engagement, army, navy, and RAF officers and enlisted men were seconded to the Sultan’s Armed Forces (SAF), and many more ex-servicemen served as soldiers of fortune under lucrative contracts. These men led their tough Arab soldiers to one of the few Western victories of the Cold War.

The war was fought almost exclusively in Dhofar, Oman’s southernmost province. What in 1963 had been a localized revolt by some disgruntled Dhofari tribesmen, quickly mutated into a full-blown communist insurgency. The main reason for this was Aden, Oman’s southern neighbor, turning communist soon after its independence from Britain in 1967.

Operating from the haven of the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY), as Aden was then known, the PFLOAG had achieved control of most of Dhofar by 1970. The threat to the rest of Oman was so acute that the aging Sultan was overthrown by his son, Qaboos bin Said, in a British-backed coup d’état.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

The new Sultan vowed to reverse the tide and win the conflict. And Britain decided to help him. The eventual allied victory is still studied as a paragon of counterinsurgency. In true Clausewitzian fashion, the military strategy served the political purpose: win the hearts and minds of the Dhofaris. Reconciliation, as opposed to annihilation, was the reasoning behind every decision, every operation. The allied forces fought not to destroy the enemy but to win him back. Recognizing that no other strategy would be enduring, they went to great lengths to secure the battlespace for civil development. Force wouldn’t suffice with these tough and proud tribesmen. If they could only show them that government rule was a much better alternative to the communists’ fairytales, they would succeed.

The obscure nature of the conflict perfectly suited the British government. During a period of decolonization and rife anti-imperialist sentiment, a full-out war on par with America’s Vietnam adventure would be politically and economically unfeasible. The British sun had set.

The conflict’s obscurity, however, also suited the SAS operators who took part in it. This was a time before the Iranian embassy siege and the Falklands war catapulted these warriors to the limelight; secrecy was still the order of the day. Compounding to the war’s secrecy was the nature of Oman’s political structure: no free press was allowed in the autocratic Sultanate, which, at the time, was a country under Sharia Law and very much still in the middle ages.

Operating in small teams, the seasoned men of the SAS patiently carved the path for Dhofar’s civil development — the crucial scheme to winning the conflict. They also trained, mentored, and fought alongside bands of ex-insurgents who gradually came over to the government’s side. These bands became known as firqats.

Additionally, the SAS were involved in some covert cross-border operations inside the PDRY that were up until recently highly classified.

And topping all else, they fought a battle by a medieval fort against all odds; a battle that has achieved legendary proportions and incites controversy to this day. After much sweat and blood, victory was eventually achieved in 1976. Keep an eye out for more articles on how they did it.

COMMENTS