Last week, a number of media outlets pounced on the idea the U.S. Army may be trying to turn its gun duties over to artificial intelligence, prompting a flurry of headlines about robotic killing machines and allusions to the popular “Terminator” franchise. The truth, however, isn’t quite so apocalyptic, and may well help make American trigger-pullers more capable and accurate in a fight.

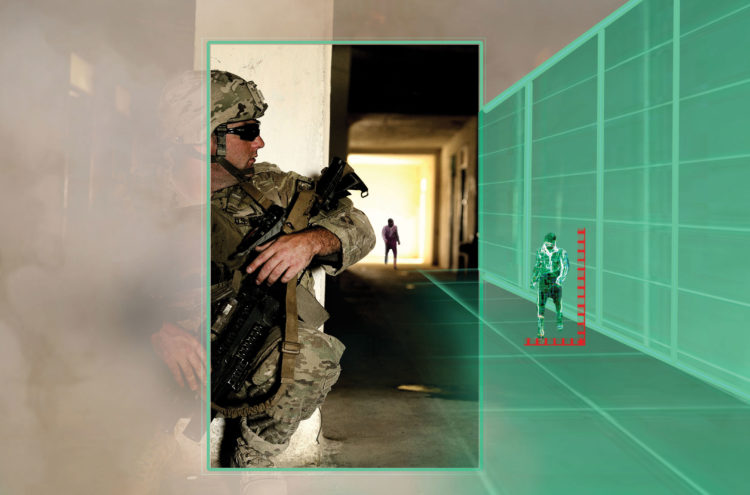

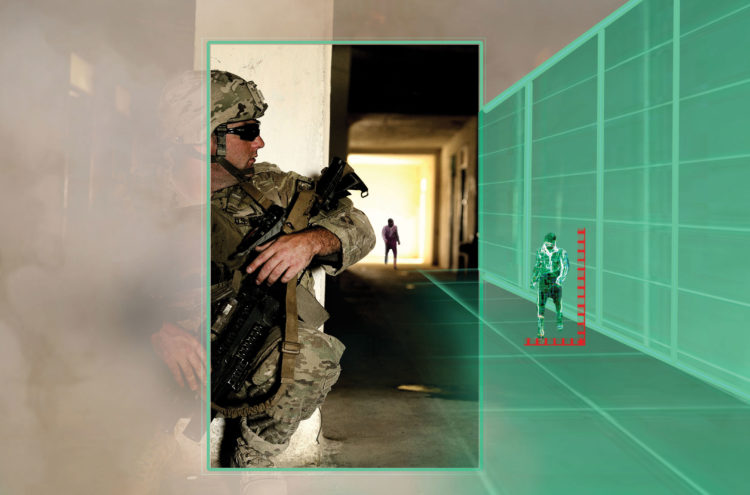

Ominous name notwithstanding, ATLAS, which stands for Advanced Targeting and Lethality Automated System, doesn’t intend to actually fire any rounds itself. Instead, the program is intended to aid human war-fighters in identifying, prioritizing, and engaging threats through an advanced targeting apparatus. ATLAS would help spot enemy positions and determine which ones pose the greatest threat to American forces. It could also assist with accuracy by ensuring the barrel of the weapon is pointed precisely at an identified threat, but the act of pulling the trigger–of ending a life– would still remain squarely in the soldier’s hands.

“Envision it as a second set of eyes that’s just really fast,” Army engineer Don Reago told Breaking Defense, “[like] an extra soldier in the tank.”

Following the media response, the Army changed the language in its request for information regarding expansion of the program to better reflect the stated intent of the initiative, dodging more clickbait criticisms about killer automatons wandering the wastelands of future battlefields. That isn’t to say that the Army has never dabbled with the idea of fully-autonomous battlefield robots under ATLAS, but in its current iteration, the program is more about smart targeting than anything else.

The backlash regarding ATLAS echoes similar controversies surrounding both Google and Microsoft partnerships with the Department of Defense in recent years. Google famously backed out of an initiative that would have aided the Pentagon in sifting through intelligence data feeds to more quickly identify threats thanks to a popular backlash from within the company and the tech community as a whole. Microsoft faced similar trouble with its Integrated Visual Augmentation System, or IVAS, but thus far, claims it intends to maintain the contract, despite the backlash.

The ethical debate surrounding robotic war-fighters is an important one, but all too often these debates are colored by popular perceptions rather than the nuts and bolts of the enterprise in question. Artificial Intelligence does not have to manifest in the form of an omnipotent, fully-networked overlord as depicted in countless films. Elements of AI can actually be found in a number of things most Americans use every day, like the Google Image Search function, which assesses images and delivers pictures to you based on your search criteria without any need for human assistance.

More importantly, while America stokes its own AI fears, nation-level opponents like China continue similar programs unabated.

“While outside groups will undoubtedly have concerns about the ATLAS program, even if the requirements are altered, the U.S. military is attempting to take the challenge of AI seriously across several dimensions,” says Michael C. Horowitz, an associate professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania and a senior adjunct fellow at the Center for New American Security.

However, it is important that the ethical quandaries these controversies are rooted in remain at the forefront of the discussion as AI finds its way into more defense initiatives. ATLAS may not be a trigger-puller, nor is Microsoft’s IVAS, but someday, a similar system likely will be.

“Between the efforts of the Defensive Innovation Board, the Joint Artificial Intelligence Center, the new National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, and others, now is the time to have these important conversations,” said Horowitz.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS