The Russian invasion of Ukraine has raised fears among the public about the use of nuclear weapons in Europe or against the United States. This level of concern has not been seen since the end of the Cold War.

NATO countries have been taken aback by Russian President Vladimir Putin’s implied threats to use nuclear weapons against “whoever interferes with us” in Ukraine, and his placement of additional nuclear officers on shifts under a “special regime of combat duty.”

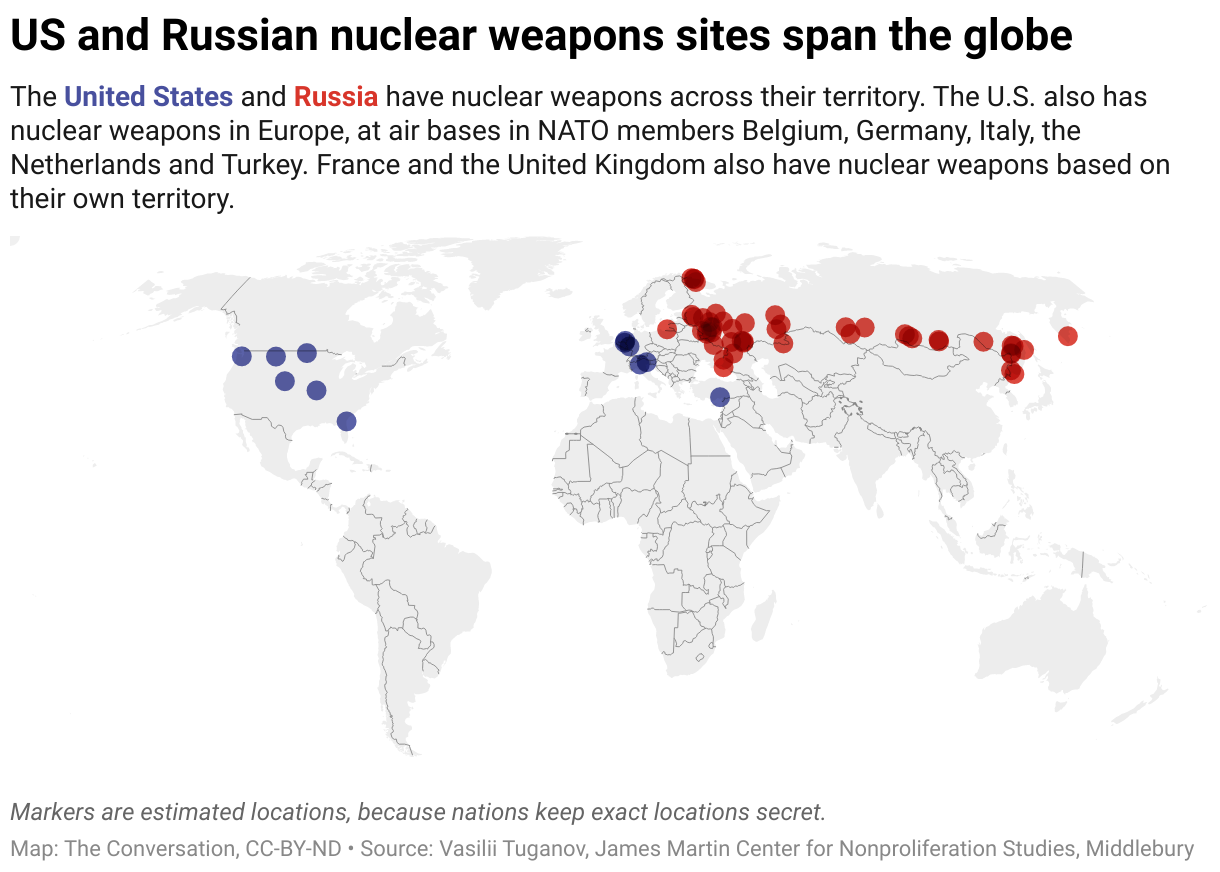

Both Russia and the U.S. have thousands of nuclear weapons, most of which are five or more times more powerful than the atomic bombs that leveled Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. These include about 1,600 weapons on standby on each side that are capable of hitting targets across the globe.

Those numbers are near the limits permitted under the 2011 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, often called “New START,” which is the only currently active nuclear arms control treaty between Russia and the U.S. Their arsenals include intercontinental ballistic missiles, better known as ICBMs, and submarine-launched ballistic missiles, as well as missiles launched from specialized aircraft. Many of those missiles can be equipped with multiple nuclear warheads that can independently hit different locations.

To ensure that countries follow the limits on warheads and missiles, the treaty includes methods for both sides to monitor and verify compliance. By 2018, both Russia and the U.S. had met their obligations under the New START, and in early 2021 the treaty was extended for five more years.

Both nations’ nuclear arsenals also include hundreds of shorter-range nuclear weapons, which are not covered by any treaty. Currently, Russia has nearly 2,000 of those, about 10 times as many as the United States, according to the most widely cited nongovernmental estimates.

About half of the roughly 200 U.S. shorter-range weapons are believed to be deployed in five NATO countries in Europe: Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands and Turkey – though the U.S. does not confirm or deny their locations. In wartime, allied planes would take off from those locations and fly toward their targets before dropping the bombs.

Two other NATO members, France and the United Kingdom, also possess their own nuclear arsenals. They have several hundred nuclear weapons each – far fewer than the nuclear superpowers. France has both submarine-launched nuclear missiles and airplane-launched nuclear cruise missiles; the United Kingdom has only submarine-launched nuclear weapons. Both countries have publicly disclosed the size and nature of their arsenals, but neither country is or has been a party to U.S.-Russian arms control agreements.

The U.S., U.K. and France protect other NATO allies under their “nuclear umbrellas” in line with the NATO commitment that an attack on any one ally will be viewed as an attack on the entire alliance.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

China’s nuclear arsenal is currently similar in size to the U.K. and French arsenals. But it’s growing rapidly, and some U.S. officials fear China is seeking parity with the United States. China, France and the U.K. are not subject to any arms control treaties.

India, Pakistan and Israel have dozens of nuclear weapons each. None of them has signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, in which signatories agree to limit the ownership of nuclear weapons to the five permanent members of the U.N. Security Council, each of which possessed nuclear weapons before it was signed.

North Korea, which also has dozens of nuclear weapons, signed that treaty in 1985 but withdrew in 2003. North Korea has repeatedly tested nuclear weapons and the missiles to carry them.

There used to be nuclear weapons in other places, too. At the time the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, the republics that became Belarus, Ukraine and Kazakhstan had former Soviet nuclear weapons on their territory. In exchange for international assurances for their security, all three countries transferred their weapons to Russia.

Fortunately, none of these weapons have been used in war since the U.S. bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. But as recent events remind us, the risk of their use remains a frightening possibility.

***

This piece is written by Miles A. Pomper, Senior Fellow, and Vasilii Tuganov, Graduate Research Assistant from the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury. Want to feature your story? Reach out to us at [email protected].

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

COMMENTS