The Office of Strategic Services Is Born

President Roosevelt liked the idea. However, he wanted to keep COI’s Foreign Information Service (FIS), which conducted radio broadcasting, out of the military’s control. It was then decided that the “black” (covert) and “white” (overt) propaganda missions be separated giving FIS the official side of the business. FIS and half of COI’s staff were sent to the new Office of War Information.

The remainder of COI’s operatives were then earmarked for what was to become the Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

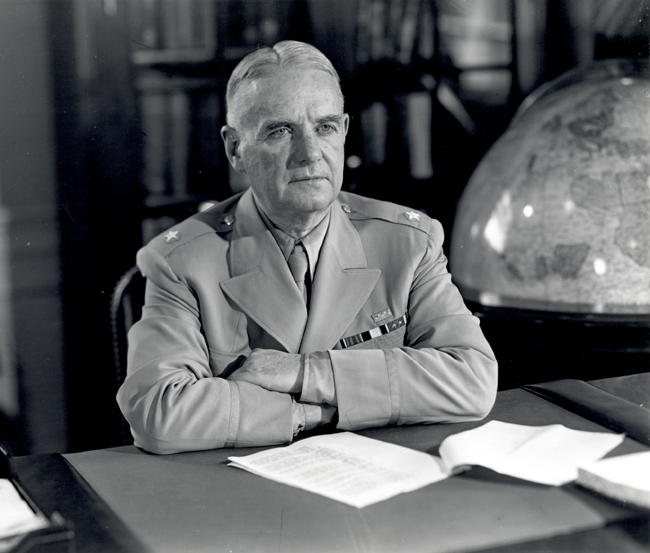

On June 13, 1942, the OSS was formed. Donovan chose the name that reflected his sense of the strategic importance of intelligence and special operations.

The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines for all branches of the United States Armed Forces. However, due to the wartime footing, other OSS functions included the use of propaganda, subversion, covert operations, guerrilla warfare, and post-war planning.

Under the expert leadership of Wild Bill Donovan and a crash course of intelligence from the British, OSS expanded quickly. Just a few months after being formed it was instrumental in providing excellent and timely intelligence for the Operation Torch landings in North Africa in November of 1942.

Donovan had already provided the State Department with desperately needed French-speaking officers in French-held North Africa to act as “vice-consuls.” Thus, he the OSS had won the grudging respect of the State Department. With Donovan’s leadership and outstanding training by the British, OSS began to quickly build a worldwide clandestine intelligence capability.

The Glorious Amateurs and the British Teachers

The first COI/OSS officers arrived in Britain in November 1941 before the U.S. was even in the war. They leaned heavily on the British for training and information to get off the ground. The British, used to operating on more of a shoestring budget, happily partook of the seemingly endless resources of the new American unit.

The relationship was slow to blossom. The British were cautious at first, worrying that the neophyte Americans could compromise their hard-earned operatives in Occupied Europe. Despite this, the two sides grew interdependent on one another by the war’s end. The operational marriage would be extremely beneficial to both sides and lay the groundwork for the close cooperation and trust the two countries still enjoy.

Donovan recruited an eclectic group of volunteers that he described as “Glorious Amateurs.”

Donovan described the perfect OSS men as “PhDs who can win a bar fight.” OSS wanted smart self-starters who could think on their feet.

At the peak of war operations in late 1944, OSS had grown to over 13,000 personnel. About one-third of whom were women.

These men and women formed the backbone of the CIA and later the U.S. Army Special Forces.

Enter the CIA

When the war ended, the handwriting was on the wall for OSS. President Truman disliked Donovan and the OSS. Donovan’s plan to keep a peacetime intelligence service was filed away but ignored. OSS was disbanded on October 1, 1945.

Two years later Truman approved the new organization called the Central Intelligence Group (CIG) until the National Security Act of 1947 turned CIG into the Central Intelligence Agency. The CIA was to perform many of the missions that Wild Bill Donovan had advocated for his proposed peacetime intelligence service. CIA became what General Donovan had initially proposed.

The modern-day CIA and the U.S. Special Operations Command owe a great deal of their legacy to OSS and Wild Bill Donovan. They still employ some “PhDs that can win a bar fight.”

COMMENTS