On 16 March, Thailand-based USAF 21st Special Operations Squadron helicopters inserted Davis, Lamotte, and four indig into a Prairie-Fire target some 12 kilometers west of Kham Duc, the site of an old SF ‘A’ camp that had been overrun by the NVA (North Vietnamese Army) in early 1968. From the moment the team hit the ground, the mission was plagued by communications trouble. Once on the ground, Lamotte couldn’t make radio contact with any of the support aircraft. Because the choppers and Covey had launched from a distant NKP, they had virtually no time on-station due to fuel constraints. As a result, they had to depart the area immediately, leaving RT Copperhead on its own.

During the night, Lamotte was still unable to contact Covey or any of the night airborne-command aircraft, code-named Moonbeam and Hillsborough. The team could hear conspicuous enemy movement behind them throughout the night. Just before first light, team members moved out of their RON site, fearing a dawn attack. Lamotte made repeated efforts to establish radio contact, but each time, he came up empty. RT Copperhead was truly alone, except for the NVA who were by now stalking them like animals. When Davis realized the NVA were trying to push RT Copperhead toward a ridge line, beyond which lay open fields with no cover, he directed the team into a tangle of fallen trees, positioning them near the uphill end of the haphazardly stacked logs.

The communications drought continued, and by early afternoon the team was very tense, sensing that the NVA were about to close in on them. Lamotte recalled years later that “Ricardo (Davis) came up to me, trying to bring a little levity to our situation, and told me, ‘I’m going to take a shot at you pretty soon, just so you know what it feels like.’” Lamotte smiled, but had the distinct feeling he would not need Ricardo’s help getting shot at because Lamotte could see Anh, the team’s tail gunner, signaling urgently that NVA soldiers were close. Very close.

Before Lamotte could finish processing Anh’s warning signal, his hand gripping his throat, AK-47 gunfire erupted on three sides of RT Copperhead. Four rounds slammed into Lamotte’s ruck sack, driving him face-first into the ground and destroying his main radio, a PRC-25. Lamotte said, “As I was falling to the ground, I heard Davis call out, ‘Jim!’ I yelled back to him, ‘Wait one, Dave.’ I bounced right up, firing on full automatic. I fired at least three magazines before I slammed a magazine in at a bad angle, causing the CAR-15 to jam.”

Sudden, eerie silence

Then suddenly, there was a complete, unearthly silence. And in that soundless instant, Lamotte somehow knew Davis was dead.

Lamotte quickly searched around for Ahn, only to discover the fearless Nung lying motionless. He had been shot at the base of the spine. “I knew Ahn wasn’t going to make it, so I took out a syrette of morphine for him. My hands were shaking so badly that I had to try a second and third one before I could give him relief.”

While Lamotte was tending to Ahn, the silence was broken by a voice speaking perfect English. It was an NVA soldier with a message directed personally to Lamotte. “American, why don’t you just surrender?”

“I flipped out,” Lamotte said, “I rolled over onto my knees, yelled, ‘Fuck you, you motherfuckers!’ and fired on full automatic, which was pretty stupid on my part, because they returned fire, a lot of gunfire.”

After this brief responding salvo, the NVA weapons again fell suddenly and inexplicably silent. A second voice, this one speaking Chinese, exhorted RT Copperhead’s Nungs to “Surrender the American.” The Nungs and Lamotte answered in unison with a full-automatic response, and the firefight was once more up and running at full rage.

Lamotte had been so focused on the taunting NVA that he failed to see an enemy soldier taking aim at him from his left flank. In a remarkable display of courage and loyalty, the team’s M-79 grenade man, Troung Van Lac, threw his body in front of Lamotte just as the enemy fired. Although Troung caught a bullet in the side, he was nonetheless able to kill the NVA soldier. Moments later, another NVA soldier took aim at the unsuspecting Lamotte, and again Lac shielded him with his body, catching a second enemy round, this one in his arm. The impact slammed Lac into Lamotte, who spun to his left and fired his weapon, killing the NVA troop. Unable to hold the grenade launcher because of his arm wound, Lac remained undaunted and, in a remarkable show of determination, told Lamotte where to aim the M-79 so Lac could pull the trigger and “kill beaucoup VC.” It was a lesson in dedication and determination Lamotte would never forget.

During the next lull, as the NVA maneuvered to surround RT Copperhead, Lamotte and the three remaining Nungs huddled together in the tangle of dead trees for a brief, reflective moment. “We got together. The PRC 25 was wiped out. I thought the URC 10 (emergency radio) was dead, too. We hadn’t heard from anyone since our insertion. We cried. Then we smiled at each other. We realized that we were going to die,” Lamotte said.

As that gut-wrenching realization was settling in, and as each man quietly made his final accommodations, Lamotte heard a distinctly American voice faintly saying, “Roger May Day signal. Roger May Day signal.” Lamotte thought he was hallucinating, but what he was hearing was a pilot’s voice coming over his secondary, emergency radio, the URC-10 he thought had been destroyed during the firefight. Miraculously, it was still working. But Lamotte hesitated. “I somehow knew I was dead already and I didn’t want to bother with it. I was ready to die. Right there.”

But the Nungs weren’t. Sang, the indigenous team leader who recovered the radio from where Lamotte had dropped it, thrust the small handheld radio into his hand and depressed the ‘speak’ key. He forced Lamotte to communicate. The calm, at-your-service response of the American pilot on the other end broke him out of his debilitating ‘my-life-is-ending-now’ trance. The pilot said two F-4 Phantoms were moments away and ready for action.

While Lamotte worked the radio, the NVA continued closing in from all sides. Lamotte gave the jet fighters the map coordinates of the team’s location, but the pilots wanted something more precise. It was not for nothing that they were referred to as ‘fast movers’ and their high speed often resulted in something less than perfect placement of munitions. It was for this reason they asked Lamotte to pinpoint his location. They wanted to be able to calculate their margin of error, which in this case ranged from slim to non-existent. He popped a shiny at them and told them to bring the gun run right on top of it.

As the F-4s screamed down from above, the quartet of RT Copperhead survivors burrowed under the logs like the snakes they were named after. It was done just as the NVA overran its position. “The NVA were doing as they always did, getting close to the belt, as they called it, our belt. However, the Vulcan cannons (of the F-4s) were screaming. We could smell the cordite, the blood, the guts. We didn’t have a second to spare. Hell, if those Phantoms had been a second or two later, the NVA would have killed all of us. All of us.”

As the fast movers finished up their first run, Covey noticed another wave of NVA moving toward the fallen trees. Covey quickly got word to the F-4s, who banked a sharp turn, and came roaring back with an offering of 250-pound bombs. The bombs hit so close to the team they knocked Lamotte flat on his face. Once again, Uncle Sam’s Air Force had saved the day for a SOG recon team. Lamotte spent the next four hours orchestrating airstrikes around the team, as more and more air support arrived in response to the Prairie-Fire emergency. The situation rapidly turned into a symphony of destruction. The secondary explosions were too numerous to count.

Yet, even after four hours of brutal pounding, the resilient NVA amazed Lamotte when they opened fire and heavily damaged the first two helicopters as they made their approach to extract the team. The two choppers were forced to break off and seek safely. However an audacious third Air Force HH-3 pilot, seemingly unfazed by what he had just witnessed, somehow managed to slip safely into a nearby stand of trees, and the remnants of RT Copperhead were able to reach it under a hail of covering fire. Lac had lost so much blood he couldn’t walk or move, so Lamotte had taken the six-foot strand of rope he carried for emergencies and tied Lac to his back. This left his hands free to fire his CAR-15 as he fought his way toward the waiting helicopter.

After setting his wounded grenadier into the helicopter, Lamotte turned and observed more than a dozen NVA soldiers running around some trees and heading straight toward the already revving HH-3. “As I charged off the chopper toward them, one of the Air Force pararescue airmen tackled me. They dragged me onto the chopper. I wanted to kill those fuckers that got Davis and then go get his body. Again, I was flipping out as the damned helicopter lifted off. I couldn’t bear to leave him and Ahn behind.”

What was left of RT Copperhead made it back to NKP safely. But once he was finished being debriefed, Lamotte insisted that a Bright Light rescue-and-recovery team be sent immediately back into the target area to retrieve his fallen teammates. He volunteered to lead the effort; in fact, he insisted that he be allowed to lead it. His request was resoundingly rejected. The target was just too hot.

When the Blackbird (An unmarked C-123 cargo aircraft) ferrying RT Copperhead from NKP back to Da Nang Air Base landed, Werther and many of the U.S. and indig recon men, including Captain Welch, were there to greet it. Werther, a pained and grief-stricken look on his face, could say nothing. He and Lamotte embraced silently, like brothers who had lost close family members. Both were deeply affected by Davis’ and Ahn’s deaths, more deeply than even they could realize at the time.

Recoup, regroup

Following the memorial service for Davis, Werther and all of the Nungs from RT Copperhead took Lamotte to a special Buddhist temple in Da Nang to nurture him. When Lamotte left for Saigon to undergo a detailed debriefing and to appear before a board of inquiry on Davis’ death, Werther asked Captain Welch and Sergeant Major Charlie Vickers if he could take over as the one-zero of RT Copperhead for one mission with Lamotte and his old team once Lamotte returned from Saigon. Werther suggested it might help Lamotte resettle himself. Welch and Vickers agreed to this request. With their blessing in hand, Werther, Sonny Whong, Copperhead’s interpreter, and Sang immediately began a tough training regimen. During the day, they worked hard at honing their survival and killing skills, while at night they went to a local Buddhist temple to burn joss sticks in memory of their fallen comrades. After three days of mourning, the joss sticks were burned for future good luck.

Once Lamotte returned to CCN, Werther could tell his confidence remained uncharacteristically low. He understood why Lamotte might doubt himself; every recon man suffered through a painful self-examination when he lost a team member. Werther tactfully laid out his proposition for running one more mission as one-zero of RT Copperhead in order to help Lamotte get back on his feet. Lamotte agreed to Werther’s offer, and joined in the rigorous training. The daily exercises continued for two more weeks, right up until the team finally drew a target. It was your standard SOG mission; they would be inserted well behind enemy lines, where they were to attempt to confirm the existence of a suspected enemy bunker complex and rest area along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

A new mission

The 10-man effort launched from Quang Tri. With five men on each of two 101st Airborne choppers, RT Copperhead enjoyed a flawless insertion into the target area. After waiting 10 minutes to make sure all was quiet, Lamotte gave the ‘team okay’ to Covey. The team then moved out in the direction of the possible target. With Cau taking the point-man position, RT Copperhead made its way in a line formation according to the standard method of jungle movement: 10 minutes of very careful walking, followed by a stationary pause of 10 minutes to listen. As nightfall approached, Cau and Sang found a good RON site above a trail that ran near a ridge line. To be extra cautious, Werther passed it by and had the team move into a second, diversionary RON. Just at last light, the team abandoned the false site and returned to its preferred RON. The team then spent a restful, uneventful night.

At first light, Covey checked in with RT Copperhead and gave Werther an exact fix on the team’s location. Covey then headed farther north to insert another recon team in an unrelated operation. While Covey did his thing, RT Copperhead moved south, parallel to the ridge line, until it found what was clearly a very heavily traveled trail, one with hundreds of NVA boot prints in evidence. All the prints were pointing south down the trail. When Covey reappeared overhead, Werther took the opportunity to get another exact position fix. The team continued moving south for another hour until it was stopped in its tracks by the sounds of clanging pots and pans and the smell of cooking fires.

When two NVA soldiers crossed the trail in front of them, Lac and Sang took them out with single shots. The two gunshots instantaneously turned the NVA breakfast bivouac into a beehive of activity. Most of the disrupted troops charged north toward RT Copperhead, which had immediately executed a fallback toward the ridge line where Werther had received his last fix from Covey. Needless to say, its return progress was made at a much quicker and noisier pace. The need for stealth had vanished in a heartbeat; now it was a matter of running for their lives.

RT Copperhead took up a defensive position. Within minutes, a line of eight NVA troops was moving up the mountain toward them. They were unaware of the team’s exact location, and were probing in the hopes of finding them. Werther pulled out his sawed-off grenade launcher and signaled Lamotte to use his as well. Two of the Nungs took notice and added their M-79 firepower to the first salvo fired toward the advancing NVA soldiers. The four high-explosive rounds hit the unsuspecting enemy with devastating force. All eight died instantly.

Another wave of determined NVA, still unaware of RT Copperhead’s precise location, moved steadily up the mountain looking to attack as soon as they could pinpoint the team. As they advanced, Lamotte moved to the right flank, where he and a Nung team member had already killed several NVA. During a brief lull, Werther contacted Covey and reported, “We’re in heavy contact, over!” Covey calmly replied that he had help standing by. This was good news, excellent news in fact, but Werther opted to delay asking for a gun run by the air assets. “We were kicking Charlie’s ass without any help and it felt good. It felt real good, actually,” he said. “They kept coming, unclear as to where we were exactly, and we mowed them down, mostly with single shots or M-79 fire.”

Again, Werther heard a torrent of heavy gunfire from the right flank. When he made his way over to that side of the team’s perimeter, he was amazed, but pleased, to find Lamotte smiling at a pile of deceased NVA who died trying to reach him and his teammate. “I’ll never forget that moment,” Lamotte said, “when Bill came over to me and said, ‘Jesus, you’ve been busy. Real busy.’ And I didn’t say it out loud, but to myself I said, ‘this is Ricardo’s revenge.’” The monkey had scrambled off Lamotte’s back, and it was business as usual.

As Werther appraised the team’s admittedly dicey situation, he saw a full NVA platoon massing down the hill. It was clear it was preparing to deploy against RT Copperhead. These new troops were in addition to those that were already hurling themselves against the team from three sides. RPGs screamed over their heads and exploded in the trees above them. Another barrage of RPGs was launched just as a NVA machine gun opened fire from the left flank. A fusillade of M-79 fire from Werther and his M-79 grenadier silenced it, but the RPGs kept right on coming.

As the NVA platoon finally began advancing up the mountain, Werther called for the first of the loitering A-1Es to make a bomb run. The old warplane instantly delivered 500-pound bombs dead-center into the advancing NVA. As the RT Copperhead team members were bounced by the concussions and showered by debris, a second A-1E roared across Lamotte’s right flank, nailing the enemy troops in their tracks with its deadly rain of ordnance. As the smoke and dust cleared, all the team could see was a twisted mass of trees and bodies.

As devastatingly effective as these runs were, there was no time-out in the action. Werther immediately vectored another airstrike toward what appeared to be a bunker complex farther down the mountain from his position. The fighters roared in, right on target, and hit another bullseye. The bunker complex erupted in a violent explosion, followed immediately by a series of secondary detonations. Score another big one for TAC air.

In typical understatement, Covey announced to Werther, “The AO is too hot. We gotta get your asses outta there.” Werther agreed, looked at his watch, and discovered that the team had been in heavy contact for 20 minutes. Somehow it had seemed longer. What a day we’re having, he thought. We have no wounded, no dead. He crawled over to Lamotte to let him in on the latest developments and found the Detroit street fighter back at the top of his old fighting form. Lamotte gave him a giant bear hug and said with a big shit-eating grin, “We’re kicking their ass!”

Werther told Lamotte to save CAR-15 ammo and start tossing hand grenades instead. Shortly after several fragmentation grenades had been thrown down the hill, Werther yelled, “Here they come!” The enemy was rushing the team, perhaps in a desperate effort to ‘hug the belt.’ The team responded instantly, just as it had been trained to do.

“Grenade!” Lamotte yelled, one of the single most frightening words a combat soldier can ever hear. The entire team ducked in wonder as an American-issued hand grenade exploded nearby. Werther looked at Lamotte and the Detroit tough guy’s shit-eating grin had been replaced by a very sheepish one. “Mine hit a tree and bounced back,” Lamotte admitted. No one was hurt, in fact, everyone was laughing at Lamotte’s misguided effort.

Mass carnage

The enemy launched yet another wave of attacks on the team’s right flank. RT Copperhead dug in more stubbornly while continuing to strike like a pit viper. Enemy dead were stacking up like cordwood all around their position. Werther counted more than 60 bodies spread out down the mountainside. Those were the bodies he could see. In addition, Lamotte and his indig had stacked up dozens more on the right flank. It was mass carnage, pure and simple.

Covey finally gave Werther a compass heading to an LZ and then directed more airstrikes onto the hard-charging NVA. RT Copperhead moved away from the killing zone and into a small, wooded patch atop the ridge line. It was time to get out. When the first helicopter dropped extraction ropes to the team, Lamotte asked Werther if he could deploy a claymore and be the last man out. Werther nodded yes, as the first five men, including Werther, were lifted out.

Once airborne, Werther kept a worried eye on the second extraction chopper. String extractions were always nerve-racking and dangerous. So many things could, and often did, go wrong, much like what was transpiring below. Instead of lifting straight up through the jungle canopy as it should have been doing, the chopper was moving forward and dragging the remaining team members through the jungle, bouncing them off trees like puppets on strings. Werther’s group had been pulled up and out of the jungle in a perfectly executed bit of chopper piloting, so he couldn’t understand what the problem was with the second chopper. All these pilots were the best and bravest imaginable. What Werther didn’t know was that when Lamotte detonated two claymores right below them, it shocked the hell out of the helicopter crew and caused the pilot to lurch forward, momentarily forgetting the five RT Copperhead men he had in tow. He could only watch in despair.

As the battered ensemble emerged from the jungle, Werther quickly counted five heads with relief. But his relief was short-lived, as he realized that Lamotte appeared unconscious. Not only that, but he was hanging by his arm from the wrist strap of his McGuire rig. Nothing else was securing him. He could plummet to his death at any moment. Because there was no safe clearing in which to set down, Lamotte was going to be left twisting in the wind for the long flight back. Werther held his breath the whole way, his heart pounding harder than it had during the firefight.

Werther was first to land at Quang Tri, and he was instantly out of his rig and on hand when Lamotte’s limp body came bouncing in along the ground. Werther quickly reached him in the cloud of dust being kicked up by the rotor wash. He anxiously cut the hand strap and rolled Lamotte over. Lamotte gave Werther a dizzy grin and said, “I must have passed out, Bill. My back, my legs, they really hurt. The pilot must have thought the claymores were incoming.” After giving him a few minutes to recover, Werther lifted Lamotte to his feet. “Damn Bill,” Lamotte said. “We offed a lot of people today without a single casualty. Thanks for getting me back on the horse.”

“Davis would have been proud of us today, Jim,” Werther replied.

Once they cleared the LZ and settled the indigenous team members, Lamotte and Werther made their way to the launch commander’s office, where Major Bill Sheldon congratulated them on completing a very successful mission. He told them the entire bunker complex appeared to have been destroyed. There were so many secondary explosions, Covey couldn’t count them all.

Martha Raye weeps for Ricardo

At CCN a few days later, the much-loved female singer, Martha Raye (who had been made an honorary Green Beret) returned to the small bar in the recon area where earlier that year she had sung a duet with Ricardo Davis. She recognized Lamotte, and with her trademark enormous smile, asked him where Davis was. “I had to tell her the bad news,” Lamotte said. She went outside, where Lamotte found her crying like a baby. “I put my arms around her and we cried our eyes out together over Ricardo.”

A few months later, Lamotte made the sobering drive to Carlsbad, N.M., where he had to try and explain to Davis’ wife, Nellie, and her four children what happened on that fateful day in March 1969. “She had raised hell about his death,” Lamotte said. “I stayed up with her all night, explaining to her that Ricardo was not MIA as the Pentagon had listed him, but in fact he was KIA.” One of the unfortunate, but unavoidable, byproducts of the secrecy surrounding SOG operations was that often the full truth could not be told to family members about what happened to their loved ones, particularly with regards to where it happened and what exactly they were doing. Known dead left behind enemy lines were carried as MIA, even though their fellow recon men knew for certain they were not alive.

Then, Lamotte went to Fort Stockton to talk to Davis’ father, the dedicated sheriff of the little Texas town. He was very proud of his Green Beret son. His deep, fatherly grief was there, but he was not in the least embittered by his son’s death. Sheriff Davis took Lamotte to every bar in town. The sheriff got so drunk that Lamotte drove the patrol car for the remainder of the night. The next day, Lamotte met Davis’ aunts. “They were all looking at me, wondering how I’d survived while Dave hadn’t. His father told me not to let it bother me.”

Sheriff Davis offered Lamotte a job on his ranch once he separated from the service. Lamotte took him up on the offer and, after working on the ranch for a period of time, the Detroit street fighter returned to an urban environment. He was many things, but a cowboy he was not.

It would be many years before Lamotte and Werther could come to terms with the death of their friend, Ricardo Gonzalez Davis. But together, they knew that they and the indigenous of RT Copperhead had exacted a devastating revenge on the enemy that took his life, and that helped more than a little in easing their pain.

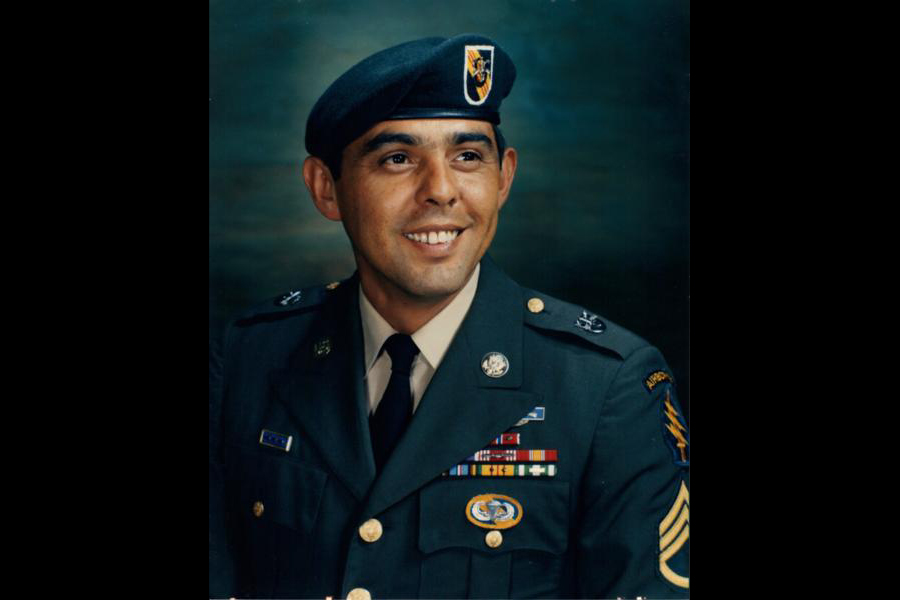

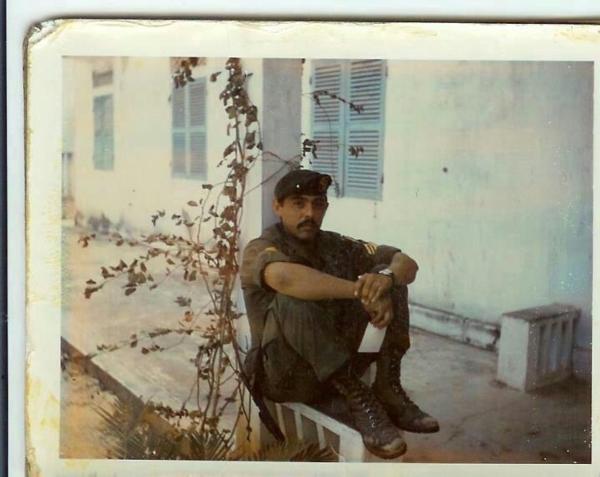

(All images courtesy of Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund)

COMMENTS