The IRGC and Lebanese Hezbollah have a well-known historical relationship that continues to this day. The IRGC deployed one of its brigades to southern Lebanon in the early 1980s to create and stand up Hezbollah. Since that time Iran has provided continuous financial and materiel support to Hezbollah, and their partnership has manifested in the form of multiple mass-casualty terrorist attacks around the globe, targeted assassinations, and military operations in wartime environments. This last element of collaboration is well-documented and provides insight into the depth of cooperation between the Quds Force and Hezbollah in their operations. Moreover, the Quds Force personnel known to have been involved in these operations continue to play senior roles in Iran’s global force projection network today.

During the Iraq War, the Quds Force teamed with Lebanese Hezbollah to train, fund and arm Iraqi Shia militant groups, and plan and execute attacks against U.S. and Coalition Forces. In one such example, Deputy Commander of the Quds Force External Special Operations Unit, Abdul Reza Shahlai, along with senior Hezbollah operative Ali Musa Daqduq, planned a sophisticated attack in 2007 that resulted in the death of five U.S. soldiers in Karbala, Iraq.

Shahlai later went on to help plan and facilitate the failed 2011 plot to assassinate the Saudi ambassador to the U.S. in Washington, D.C. Daqduq, who had been appointed in 2005 by Hezbollah to coordinate training for Iraqi militants inside Iran with the Quds Force, was detained by Coalition Forces in 2007. He was released by the Iraqi government in 2012. Reports indicate that Daqduq fled Baghdad for Lebanon after his release.

The third highest-ranking commander of the Quds Force, Operations and Training Deputy Mohsen Chizari, was also active in Iraq. Chizari was detained by U.S. forces in Baghdad in 2006 along with another unnamed Quds Force officer and detailed information on the import of sophisticated weaponry from Iran to Iraq. The Iraqi government quickly released Chizari and his co-conspirator, citing diplomatic immunity. Five years later, in May 2011, the U.S. Department of the Treasury designated Chizari, along with Quds Force Commander Qassem Suleimani, for their role in supporting Bashar al Assad’s regime in Syria.

Iran’s involvement in Syria is not surprising. Iran maintains a number of strategic interests that have been affected by the ongoing crisis, and the centrality of Syria to Iran’s regional objectives has necessitated an integrated effort. Syria has long been Iran’s closest state ally and provided crucial access to Hezbollah in Lebanon, as well as Hamas in Gaza, and Islamic Jihad in the West Bank. Iran has used Syria as a hub to finance and transport personnel, and weapons, to these groups.

Furthermore, Iran has invested in Syria as a strategic partner as part of its deterrence strategy vis-à-vis Israel and as an Arab ally in its rivalry with Turkey and the Persian Gulf states. Iran is, therefore, implementing a two-track strategy in Syria, undertaking efforts to both preserve the Assad regime for as long as possible while working to create a permissive operational environment in post-Assad Syria.

This effort has been led primarily by the Quds Force, which has deployed senior personnel into Syria in order to arm, train, and advise elements of Assad’s security forces. The assassination of senior Quds Force commander Brigadier General Hassan Shateri in Syria last month is evidence of ongoing Quds Force activity directed at the highest levels. Iran’s efforts have also increasingly involved Lebanese Hezbollah. The Quds Force and Hezbollah have cooperated in ensuring the passage of Iranian arms shipments to Syria since at least 2012. They have also cooperated to train pro-Assad forces inside Syria.

Hezbollah has recently increased its direct combat role in Syria. Hezbollah forces launched an attack in February 2013 in coordination with Assad’s forces against rebel-held villages near al Qusayr, Syria. The January 2013 Israeli strike on a Hezbollah military convoy transporting SA-17 anti-aircraft missiles revealed that the organization was working to move more sophisticated weaponry out of Syria into Lebanon. The emergence of the Abu al-Fadl al-Abbas Brigade in Syria, a conglomerate of Syrian and foreign Shia fighters, including members of Hezbollah and Iraqi militia groups which purports to protect the Shia Sayyeda Zeinab shrine and surrounding neighborhood in Damascus, could provide Iran and the Quds Force another avenue to both assist Assad militarily and influence the conflict after regime collapse.

The extent of Iranian and Hezbollah involvement in Syria reflects the centrality of Syria to both. The loss of Syria as a state ally will significantly impact Iran’s ability to deter Israel, project power in the Levant, and supply its proxies.

Iran may achieve some success with this two-track strategy, prolonging the conflict and creating conditions whereby it can retain some of its operational capacity in the Levant. The loss of Syria as a state ally, however, will significantly limit Iran’s strategic depth. A rump Alawite state cannot provide Iran with the same level of deterrence, or political and economic support as Assad’s Syria. Moreover, a rump Alawite state cannot be sustained indefinitely. Iran’s efforts in this regard offer only a temporary solution to a much greater problem.

Iran is certainly aware that the loss of Syria will significantly degrade its ability to project power in the Levant and has planned for such a contingency. In order to compensate for this loss and continue to present an effective deterrence force, Iran may look to expand its activities in other countries and regions. The interception earlier this month of an Iranian weapons shipment containing sophisticated Chinese-made anti-aircraft missiles, and large quantities of arms, ammunition, and explosive material destined for al Houthi rebels in Yemen suggests that, in at least one area, Iran has ramped up its support for militants elsewhere.

The Quds Force’s recent escalation of global activity over the past two years, including a plot to conduct a mass-casualty attack in Washington D.C., a mixed bag of failure and success in its terrorist plots against Israeli interests in Georgia, India, and Azerbaijan, and plans to carry out attacks in Bahrain, Kenya, and Nigeria, indicate that Iran is growing and operationalizing its global force projection network. This is likely an effort on Iran’s part to demonstrate that it, indeed, has a robust deterrent and retaliatory force in place. As the conflict in Syria stretches on, Damascus slips from Assad’s control, and Iran sees its strategic depth continually eroded, we are likely to see not just increasing Iranian military activity in Syria but a more risk-prone Iranian regional and global strategy.

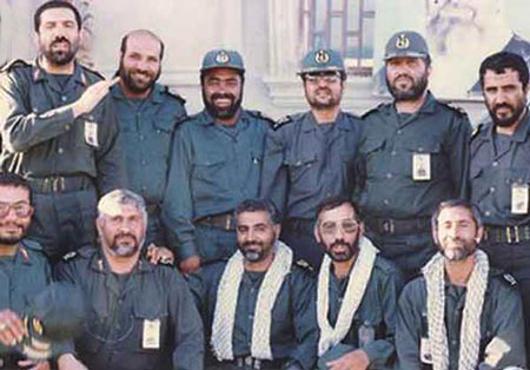

Featured image of IRGC commanders after the Iraq-Iran war courtesy of www.irantracker.org.

COMMENTS