Read A Marine goes to college Part One, Two, and Three.

After nearly two and a half years of taking extra classes each semester, accelerated courses during the summer and winter breaks, and doing internships during the hours that mere mortals were sleeping, I found myself closing in on graduation day… and once again, utterly terrified.

Leaving the Marine Corps was scary. Career retention specialists and battalion first sergeants make it a point to ensure you know that the world outside of our beloved green cocoon is a dangerous and confusing one – where there are no lifelines, no backup is coming, and the hand of fate can leave you homeless or unable to support your family. It sounds like a terrible practice – because it is – but it works wonders on the young psyche that has never had to fend for itself. An eighteen-year-old that moves out of their parent’s house and into a barracks room has little experience to pull from when leaving the Corps in their twenties, so many Marines have no reason to doubt their leadership’s account of the outside world.

My transitional anxiety had little to do with a fear of poverty – mostly because I’d grown up poor, and although I loved the Jaguar I’d bought used with my Marine Corps paychecks, I never feared a shift back toward old economy cars and crappy housing. My fears were always cultural. Would I fit in with college kids? Would I be miserable? Now, two years later I’d found that college life was pretty nice. I had a small group of friends that I felt at home with and had my ego consistently reaffirmed by good grades and college kids that thought the big, bearded guy in the weight room was scary. It wasn’t a perfect life, but it was a satisfying one – I knew that each day I was working toward a lifelong goal, and that my efforts would pay off in a better standard of living after graduation… but as graduation grew near, I found myself even more afraid of leaving school than I think I had been leaving the Corps.

You can’t get fired from the Marines. Well, you can be thrown out for any number of infractions, but they were all so egregious (murder, drugs, being a big fat-fatty) that I never had to concern myself with them. Likewise, in school you could really only be shown the door for being an overwhelming disciplinary problem or for consistently failing your classes, both of which were just as unlikely as Sergeant Hollings doing a bunch of drugs and gaining fifty pounds… so at no point from the ages of twenty-one to thirty-one had I ever really needed to face the possibility that I wasn’t good enough to find a decent job and support my family.

For the first time, I felt the overwhelming weight of expectation and the potential I’d worked so hard to cultivate. I’d seen multiple meritorious promotions in the Marine Corps, the honor roll throughout college, and all along I’d been trying to build myself into something bigger and better than I felt I was… now, with the real world waiting just beyond a short ceremony, I found myself terrified that the version of myself I’d built wasn’t as strong, or as valuable, as I’d hoped – and that this new Alex would come crashing down in the face of reality, leaving only a sad old veteran that says things like, “I wish I’d never gotten out,” over beers at the VFW.

Then there was my family. As I’ve mentioned before, few members of my family have finished college (though my mom actually graduated with her bachelor’s the same week I did – a memory I will always treasure) and they’ve all done not only well for themselves, but have established exciting and unique lives. My older brother opened his own car dealership and repair facility (which remains open and under his ownership to this day – feel free to stop by Hollings Automotive if you’re ever in Torrington, Connecticut and say I sent you) and had worked, raced, and networked his way into an executive position at the world’s largest racing school by the time I graduated. My younger brother, the heavy-set, curly haired Hollings boy who never pursued athletics like us, had found his profession in the confusing digital world of video games – landing a great job at Blizzard organizing World of Warcraft tournaments and effectively playing his favorite game for a living. Then there was me. As a Marine, I had just as “cool” a gig as they did… but as an impending college graduate, the best interviews I was able to land were all in personnel and administration for the Navy, or human resources for defense contractors. Careers with great earning potential – but lacking the romantic sense of accomplishment I learned to crave through fighting for promotions and chasing after diplomas.

After flying all over the country and interviewing for a number of jobs, I finally accepted a position working as a regional human resources manager for a large defense contractor. The scope of the job was much larger than I expected to secure on my first outing (I was to be responsible for four facilities across three states and serve as the corporate liaison for each) and although it came with a fair amount of travel, it also came with a hefty paycheck. I didn’t particularly want to be an HR guy… but the money was great, and the title made me feel like maybe I’d be able to keep up with my brothers at Thanksgiving dinner. After all, we were making guidance chips for fighter jets, we had a component on the Curiosity lander, I was responsible for the budget and local HR reps for all of New England… if my brothers were the exciting ones, I would be the successful one.

Of course, because I hadn’t graduated yet, and lacked any real experience in the private sector, it never really occurred to me to wonder why I had been offered so much so soon, or why such a great position, right down the street from my house, had been open for so long. I was just excited to be hired. After all, the Marine Corps was a tough job… how could this one possibly be any worse?

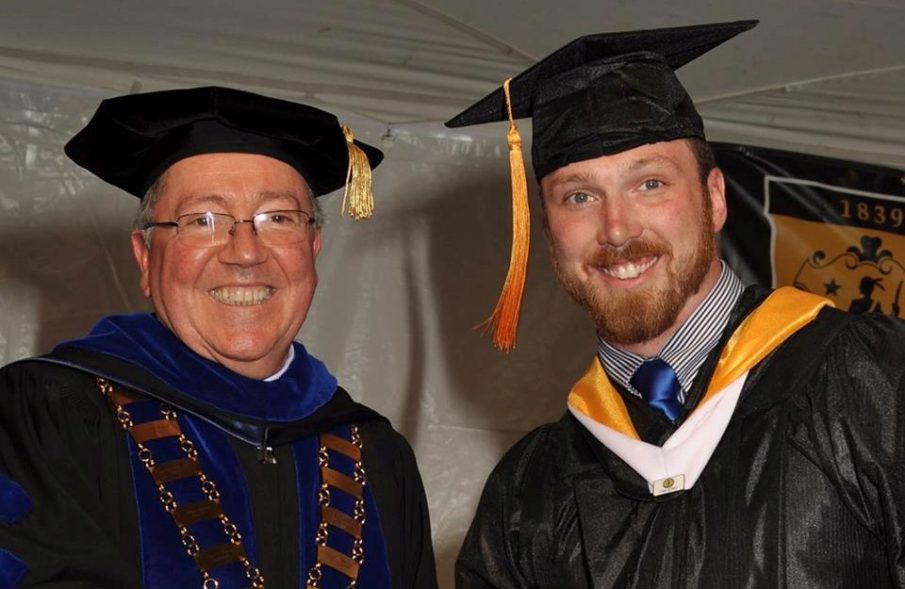

Securing employment gave me the opportunity to enjoy my graduation – which was a big deal for me, as I’d grown pretty certain I’d never be the sort of guy with a college degree. My mom came to the ceremony, my wife’s parents came too, and for a few hours, I found myself genuinely enjoying the whole ordeal without fear of what was to come or sadness over what I was leaving behind.

And then it was over.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS