Read Part 7 Here

As a Confucian society, one of the problems that many in the South Korean military faced was, and continues to persist, that they are not free thinkers. Their Special Forces are task organized like 12-man American Special Forces teams but their mission is more direct action than unconventional warfare. This makes South Korean Special Forces less like American Green Berets and more like Rangers or Marines. Their sergeants are not allowed to make decisions, unlike enlisted American sergeants. The Det K members were rotating into Korea off of combat tours in Vietnam but also had other Special Forces experience from all around the world. Injecting new thoughts and ideas into the South Korean Special Forces helped them hone their skills and bring some realism to their war plans.

If the balloon does go up, their missions into North Korea are pure suicide. “They are some of the hardest bastards I’ve ever seen in my life,” Sergeant Major Jack Hagan said of South Korean Special Forces. “I wouldn’t want to fight them.” They knew perfectly well that the threat emanating from North Korea was not to be taken lightly.

At the tail end of the 1960’s and into the early 70’s, the Det was able to begin conducting static line jumpmaster training for the Korean Special Forces as well as a some free fall courses. Korean SF was still relatively small consisting of only one Brigade at this time which allowed for a close relationship between the Det and their host-nation partners. This was also a period of turbulence as the Det was tasked out for many different types of liaison duties, was moved across three different bases in one year, and survived an attempt by KMAG to deactivate the Det. Eventually they were moved into the South Post Bunker in Yongsan and helped oversee South Korea greatly expand its SOF units in size and capabilities as Korean Special Warfare Command had been authorized in 1969.

Chuck Randall arrived back at the Det in 1971 after, “an extended vacation with the Mike Force in ‘Nam.” He found that South Korea was modernizing rapidly, on the fast track to becoming the tiger of Asia. New bridges were being built across the Han River and high rises were going up in Seoul. “In 1963 Korean exports exceeded $100 million. In 1971 they exceeded $1 billion,” Randall wrote. South Korea was experiencing an economic boom, and on their way to becoming an industrial giant. Meanwhile, the North was rationing electricity, people starved in the winters, and remained destitute. However, things were not all bright and shiny in the South as President Park declared martial law in 1972 and came under fierce criticism from the western world for human rights violations.

Over the years, SAFASIA (Special Action Force Asia) had been closing down Special Forces residence teams in places like Taiwan and Thailand, until the Special Action Force itself was eventually shut down as well. Now that the US Army was heading into a post-Vietnam drawdown, it looked as if the fix was in for Detachment K, something that the Green Berets stationed there had long feared. In 1974, the Det’s parent unit, 1st Special Forces Group was inactivated. Det K was expected to follow suit and be disbanded, but support came from an unlikely corner. The detachment’s saving grace came not from the US Army or even from Special Forces but rather than the Korean government who demanded that they keep their detachment of US Special Forces in South Korea. By now the Green Berets had been building rapport with Korean Special Forces for decades, and many of their Korean counterparts had now risen through the ranks to occupy important positions in the military and in government.

Detachment K wasn’t going anywhere, but they had been orphaned by the Special Forces community. Without a parent unit, they were no longer working for Special Forces but rather for the 8th US Army stationed in South Korea. “For the next ten years or so those of us on Det K were left out on their own, we were bastard children,” Randall said. Upon going back to Fort Bragg, they would discover that at Special Forces conferences even clandestine units like Detachment A in Berlin was represented, but not Det K.

However, this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing. “On the plus side it was wonderful, no one was looking over our shoulder,” Randall described. As Det K’s commander, he now found himself as the senior airborne officer for the entire Pacific Theater allowing him to request lots of air assets for parachute training. He found himself able to sign off on HALO/HAHO jumps before Fort Bragg ever authorized the infiltration technique, and his men became some of the best trained freefall jumpers in Special Forces. Before long, they were training the Korean Special Forces on the same techniques. “The pros outweighed the cons,” Randall concluded.

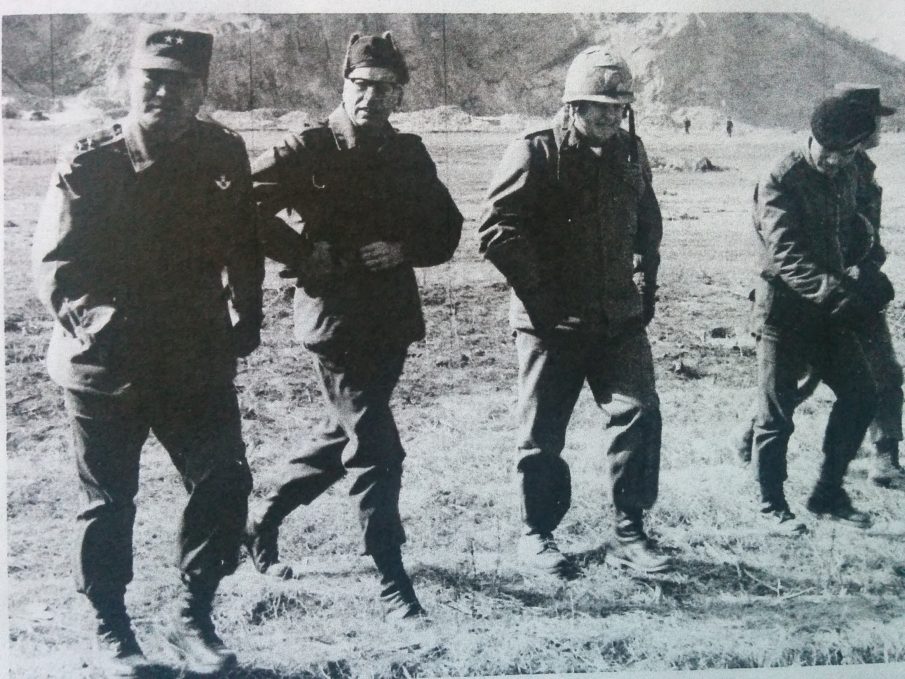

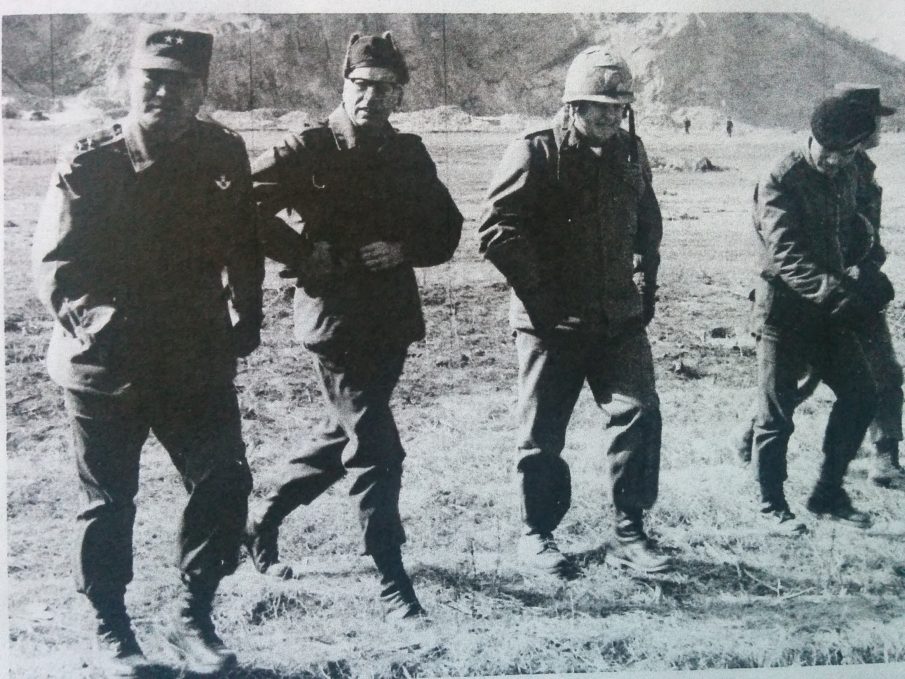

(featured image: MG Choi the commander of Korean Special Warfare Command, MG Ryan the commander of KMAG, and Major Arsenalt the commander of Special Forces Detachment K. Curtesy or Rick Lavoie)

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS