This time, instead of hiking for 23 days, DPAA arranged for an Australian company helicopter company, with a woman pilot, to take the team into an LZ near the crash site. The LZ was atop a mountain. The team had to hike down a steep mountain to get to the site where the DPAA recovery team was working, carefully digging through the jungle, taking scoops of soil and shaking the dirt through a screen searching for any minute clue that might lead them to the missing Air Force officers. On March 8, they found a few related items, but no further evidence that could lead to the possible whereabouts of 1st Lt. Eric James Huberth and Capt. Alan Robert Trent.

Shorten and the DPAA staff soon developed a pattern: arise early, eat a hearty breakfast, fly to the LZ, hike to the dig site, work all day in the jungle searching for even the most remote clue, then half the team would fly back at night because the senior Cambodian officer assigned to the detail was afraid of ghosts and refused to stay in the jungle at night. The other half of the team remained on site. The teams rotated nightly.

During this trip to Cambodia, Shorten kept a daily diary. It reflects how tough working in the jungle is, even in 2017 and how the hike up the steep hill to the LZ was a “killer.” Some nights, Shorten would remain with the team, eat dinner and climb into a hammock to sleep.

On the 10th, they found a few more possible clues. They were turned over to DPAA lab staff for further investigation. On March 11th, after flying back to the LZ and hiking down the treacherous mountain, Shorten found possible items, but DPAA officials requested that precise details about those items not be released publicly until the final mission is completed.

The recovery teams continued the arduous task of shaking the screens all day long searching for any minute piece of evidence; Shorten worked alongside of them. Again, his diary entry for March 14th reflects the rigors of working in the field. He remained on site overnight, “got around 3 ½ hours of sleep. Got up at 5 a.m., went to the bathroom, had breakfast, walked back down the hill, worked all day.”

In an interview with SOFREP on Dec. 14, Shorten said, “I have to tell you, the men and women on those DPAA field teams are amazing, dedicated, strong people who take their work seriously. Every day they worked hard. It was heart-warming for me to see just how committed every team member was to the mission. In a word, they were awesome.”

The diary entries were often the same, again stressing starting early, walking to the crash site and then they “dug, bucket and screened all day. Still no bones.” On March 18, they found a survival radio antenna “but still no bones.” After a night of heavy rain, the dirt was “like clay and hard to push through the screens.” The March 23rd entry was nearly identical: “Worked all day, found only glass, found no bones.”

On March 25th, Shorten met a representative of the DIA, who was assigned to the U.S. Embassy in Cambodia. What Shorten didn’t realize at the time was the DIA’s commitment to the POW/MIA mission has been steadfast and consistent since the first efforts to obtain accountability were launched by POW families and the U.S. government while the Vietnam War still raged and the communists brutalized most POWs. The DIA official asked Shorten to travel with him to another Cambodian crash site on March 26 of a U.S. helicopter near a Montagnard village. The duo traveled on a motorbike and, after taking a small ferry across a river to the village, they met a Montagnard who knew where the crash site was located.

After the DIA official negotiated a “finder’s fee” with a key Montagnard, Shorten and the agent were led to the crash site. Within a few minutes, they found an item that was later turned over to DPAA lab staff for analysis. Then the DIA agent had one of those unique moments in time, where he asked the young Montagnard whether the aircraft was a helicopter or a fixed-wing airplane. “The problem we faced,” said Shorten, “was the fact that the Montagnards didn’t have words that differentiate between chopper and plane, it was simply an aircraft.”

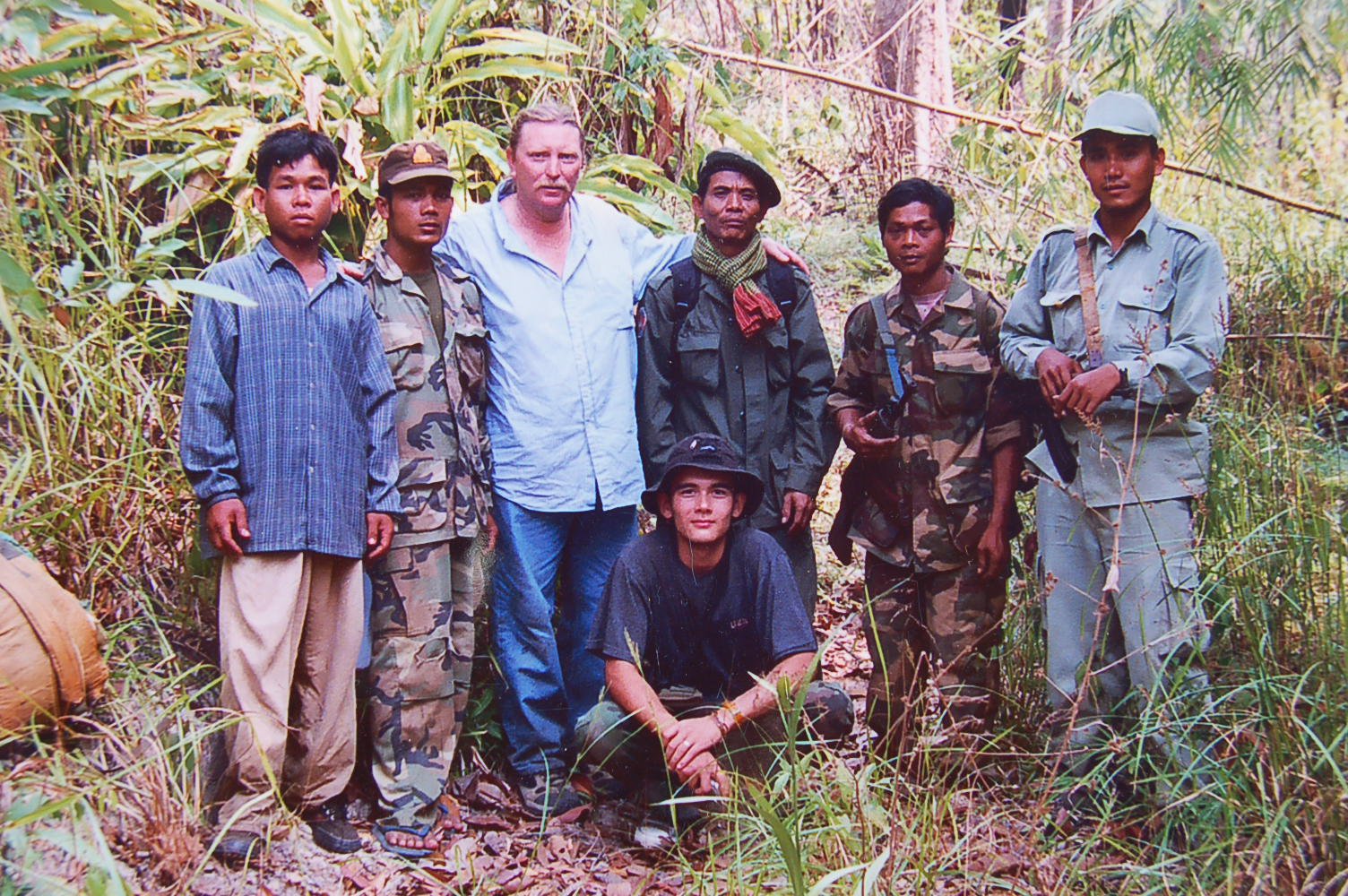

Their search yielded nothing further and they returned to the Montagnard village after a bumpy ride on motorbikes. Upon returning to the village, the DIA official asked Shorten to show the local tribesmen photos of his fearless Montagnards who served with him on RT Delaware. “I told them, here are photos of your grandfathers, who were brave warriors. They were amazed. They thought those photos were the coolest thing. Then they brought us food, beer and we had a grand time with them.”

During his final days in Cambodia, Shorten traveled to local markets, purchased two beautiful hard-carved elephants, ate indigenous food and food from restaurants with international menus. After being in and out of the jungle, hiking up and down steep jungle mountains and shaking dirt through screens all day, standing side by side with DPAA staff, the rigors had taken a toll on his 70-year-old body. Simply sitting down in a clean restaurant to eat prepared food was a big deal.

On April 1, after making the rounds to say good-bye to the DPAA team, the DIA specialist and the local Cambodian and Montagnard people who helped him during those arduous six weeks, he flew to Bangkok for the first leg of his journey back to the U.S.

He traveled with a heavy heart, realizing that after such a large commitment from DPAA and the DIA specialist that “no bones were recovered” for expert DPAA lab staff to examine was a bitter pill to swallow. “It was a long trip home, believe me,” said Shorten.

However, by Oct. 16, Shorten was in Las Vegas for the 41st reunion of the Special Operations Association, where he once again met with DPAA case workers and Ann Mills Griffiths, chairman of the Board of Directors for the National League of POW/MIA Families, who, through the league, was familiar with the 1st Lt. Eric James Huberth and Capt. Alan Robert Trent case. While there, Shorten and DPAA officials agreed that if another recovery team went into Cambodia in 2018, perhaps as early as late January or February, the former recon man could go along with them, as he had in February.

However, as noted in the National League of POW/MIA Families Dec. 7, “Update: Status of the Issue, and Vietnam’s Ability to Account for Americans Missing from the Vietnam War,” it was noted that: “A border dispute with Cambodia that was ongoing when the League Delegation visited over two years ago, continues to impede recovery operations in that area.” The league has urged officials in Laos and Cambodia “to at least temporarily set aside their political disagreement and work trilaterally with the U.S. to proceed on this humanitarian recovery to end the uncertainty of the families.”

Mills Griffiths said on Dec. 14 that, “Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen is thus far unwilling to withdraw his ‘temporary suspension’ of cooperation on the POW/MIA accounting effort. This action is tragic for the affected families and veterans and contradicts his personal pledge to me and US officials since the 1980s that Cambodia’s cooperation be pursued on a separate humanitarian basis, not linked with unrelated political differences. Until this occurred, all had characterized Cambodia’s assistance and support as ‘the gold standard’ they hoped other countries would meet. It is tragic for the affected families and veterans, including SOA’s Dr. Jim Shorten, further impeding his quest to return the two Americans he and his team were unable to return home when lost in 1970. It is a crushing disappointment.”

There’s also frustrating disappointment within DPAA, according to the update: “The greatest obstacles to increased Vietnam War accounting efforts are too few qualified scientists and unreliable funding that has caused U.S. cancellation of scheduled operations, thus sending negative signals to foreign counterpart officials, especially in Vietnam.”

That quote is all the more painful for Vietnam veterans such as Shorten and the families of the 1,602 Americans who remain missing today, according to a buried announcement in the update. It stated that key Vietnamese government officials said for the first time in more than 47 years that there were “no longer any restrictions on the number of U.S. personnel who could work in-country simultaneously, affirming flexibility in field operations and that there are no longer any areas restricted to U.S. access … including in previously sensitive areas along the northern coastal provinces.”

That unprecedented development occurred on Oct. 15 when Mills-Griffiths met with Vietnam’s Vice Minister of National Defense LTG Nguyen Chi Vinh prior to the Oct. 17 bilateral Defense Dialogue session in Washington. The vice minister repeated those promises later in the session. It’s a major step forward. However, DPAA appears light years behind in fulfilling its commitment to bring home our Americans lost during the Vietnam War.

Images courtesy of James Shorten.

COMMENTS