In June 1865, just two months after the South’s surrender, a federal judge in Virginia prepared to hand down treason indictments against Generals Lee, Longstreet, Jubal Early, and others. The judge claimed that the paroles Grant had given them were temporary military expedients, thus they did not affect the right of the government to seek criminal charges after hostilities ceased.

A general amnesty proclamation had been issued in May of 1865 but it excluded 14 classes of persons from it including Confederate generals. General Grant saved Lee and others from the hangman’s noose. Grant insisted that during the national emergency of a war, he exercised his authority under the president, who had the power to grant paroles, pardons, and clemency. The paroles he gave under the president’s authority had the full force of federal law behind them.

Grant argued that Lee and others should remain free as long as they abided by the parole terms. Further, if the government proceeded to prosecute these Confederate generals, it would cause the thousands of soldiers in the South, who had accepted similar parole, to believe it was no longer being honored.

General Grant feared this would cause hostilities to recommence at the cost of many lives.

When President Johnson still refused to prevent the indictments from being issued, Grant threatened to resign from the Army in protest if Johnson did not act.

At the time, General Grant was the most famous American in the country. Johnson knew he could not afford to lose his support. So, Johnson was forced to stop the Treason indictments of Lee and other paroled Confederates from proceeding.

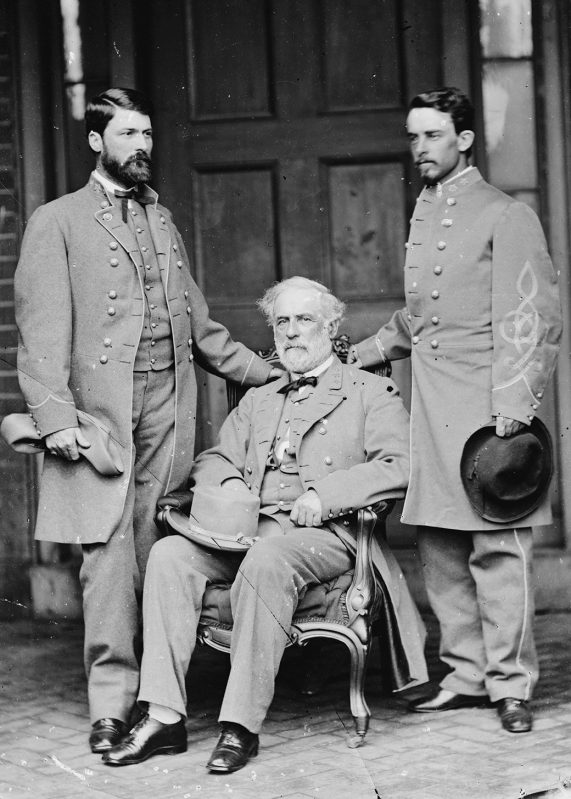

Lee never returned to his plantation home near Alexandria. Rather, his home had become a cemetery for Union and Confederate dead. Lee moved to Lexington Virginia and eventually became the president of Washington College in Virginia (now known as Washington and Lee University). He remained in that position until his death.

During the Reconstruction, Lee was a leading force in attempting to heal the wounds of division and bring the South back into the United States.

Tellingly, when he received a letter from the widow of a Confederate soldier expressing her bitterness about the war being lost, Lee wrote back to her, “Dismiss from your mind all sectional feeling, and bring (your kids) up to be Americans.”

On May 1st, 1869, Lee called upon Ulysses S Grant, who had recently been elected president. The meeting was brief and cordial, but it sent a powerful message that it was time for the South to put animosity aside and rejoin the Union.

It is ironic that although Lee was calling on the people of the South to rejoin the United States in their hearts and minds, he had been stripped of his U.S. citizenship.

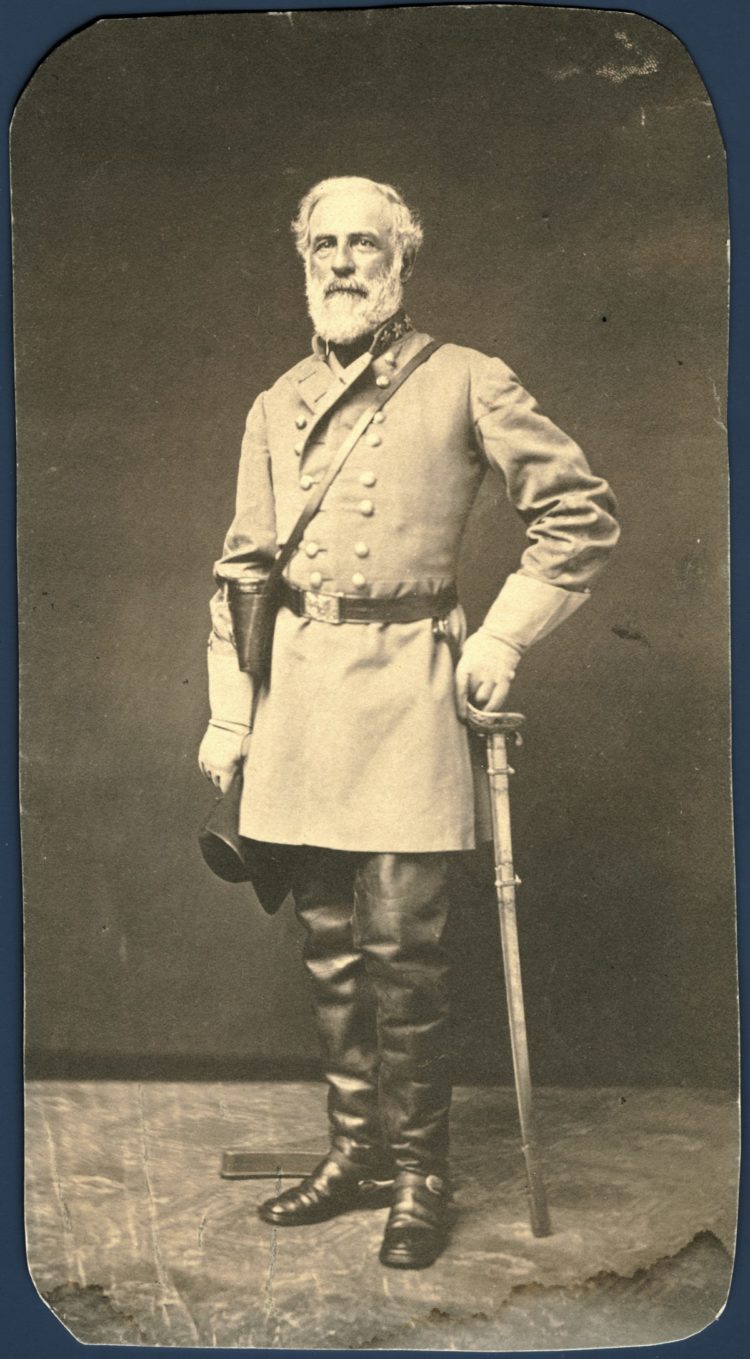

Lee had applied formally for an amnesty to the government, which would have restored his full citizenship. The amnesty consisted of an oath of loyalty to the government, the Constitution, and the United States. He signed it on October 2, 1865. The submission of this oath should have resulted in Lee receiving a full and final pardon and having his full rights as an American citizen restored. The wording of the oath was as follows,

“I Robert E. Lee of Lexington, Virginia, do solemnly swear in the presence of Almighty God that I will henceforth faithfully support, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States, and the Union of the States thereunder and that I will, in like manner abide by and faithfully support all laws and proclamations which have been made during the existing rebellion with reference to the emancipation of slaves, so help me God.”

Perhaps out of a sense of spite and anger over the assassination of President Lincoln, Lee’s amnesty application was never granted. Secretary of State William H. Seward gave Lee’s application to a friend as a souvenir. It was not seen again until it was discovered misfiled in the National Archives’ records in 1970. In 1975, President Gerald Ford granted that long-lost pardon to Robert E. Lee, and his full rights as a citizen were restored posthumously.

Recently, Under Cancel Culture, Confederate Statues Have Been Removed From all Over the US

The statue of Robert E. Lee was at the center of violent protests in 2017 in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was vandalized and the protesters scrawled anti-Trump profanities on it in white paint.

Also, the statue in Market Street Park was defaced with an expletive aimed at former President Donald Trump, according to WVIR. In addition, an illegible word was written on the back of the statue, and blue paint was spattered around its base. Part of the fence around the monument was knocked down.

One of the More Famous Statues to Be Removed Was at the Virginia Military Institute

Virginia Military Insitute, the nation’s oldest state-supported military college, had long resisted calls to remove Stonewall Jackson’s statue from its perch.

But in late October 2020, the institution’s board voted to remove the Stonewall Jackson statue after the Washington Post reported on students’ allegations of an “atmosphere of hostility and cultural insensitivity” at the school.

Kaleb Tucker graduated from the Virginia Military Institute in May. According to a recent article, “he can’t stop thinking about the indignities he endured as a black man on the campus of the country’s oldest state-supported military college.”

There is no need to wonder what Lee himself would think of the recent uproar over renaming military bases and taking down monuments erected to Confederate generals and their war dead. I suspect his advice today would be the same as he gave to that grieving widow 150 years ago.

There are several excellent books about Robert E Lee that we have linked below for further reading:

Clouds of Glory: The Life and Legend of Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause

COMMENTS