In March of 1862, Congress passed a law that authorized the government “to collect taxes on property in the insurrectionary districts within the United States.” So for the people whose land was occupied by the Federals, but were part of the Confederacy, they were assessed property taxes. This included the Lees.

Mary Lee, as the deed holder of the Arlington property, was assessed $92.70 in property taxes. She was given 60 days to pay or the government would seize the property and put it for sale at auction.

Mrs. Lee, suffering from rheumatism and living in Richmond, was unable to pay the taxes in person. She sent her cousin, Philip R. Fendall, to pay them for her. But the federal government refused to accept payment from anyone except Mrs. Lee herself. Therefore, they held her in violation. The government seized the property and on January 11, 1864, it was sold at public auction for $26,800 to the federal government. The property was valued at $34,100.

Freedman’s Village

In 1863, the government established a village for freed slaves, many of them from the Lee and Custis families on the southern portion of the Lee property. Despite reports to the contrary, the government didn’t free Lee’s slaves but Lee did himself. In keeping with George Custis’ will, all of his 188 slaves were freed.

Constructed of wood, the village buildings were 28-by-24 feet, and by late 1863, housed over 1,000 former slaves. As the people of the village died, they were buried on the property in the northeast corner of the land near the Alexandria and Georgetown Turnpike.

At war’s end, the different Freedmen villages were broken up and the people moved farther north. But at the former Lee mansion, they were allowed to stay and there remained until the 1880s.

A New Cemetery

As the war dragged on, so did the number of casualties suffered by the Union troops. The cemeteries in the Washington area were filling up quickly. General Grant’s Wilderness Campaign and the Forty Days Campaign had caused tens of thousands of casualties.

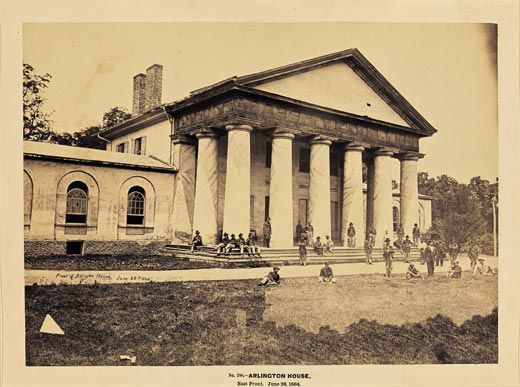

The army was looking for a suitable area for a cemetery. Brig. Gen. Montgomery C. Meigs, who was a classmate of Lee’s at West Point and had served with him, was now the Quartermaster General of the Army. He was vain, mercurial, and vindictive. He thought Lee should be executed for treason. He reported that the Lee Mansion was a perfect place for a cemetery.

The first soldier buried there was Pvt. William Christman, 21, of the 67th Pennsylvania Infantry, who was buried in a plot on Arlington’s northeast corner. Christman died of peritonitis in Washington’s Lincoln General Hospital. General Meigs ordered subsequent burials to be placed right outside the house and that Christman and other soldiers be unearthed and buried next to Lee’s home.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton agreed and endorsed Meig’s order. They would make Mary Lee’s garden a cemetery for Union soldiers.

“This and the (Freedmen’s Village)…are righteous uses of the estate of the Rebel General Lee,” said the Washington Morning Chronicle newspaper.

However, Union officers, still using the house for a headquarters, didn’t want to live right next to their buried comrades. They had the men buried farther away. Meigs was incensed to find this development.

“It was my intention to have begun the interments nearer the mansion,” he fumed, “but opposition on the part of officers stationed at Arlington, some of whom…did not like to have the dead buried near them, caused the interments to be begun.”

Meigs solved this dilemma by evicting the officers and assigning a chaplain and another officer there to oversee cemetery operations. He ordered future dead to be buried in the garden, making the house forever uninhabitable for Lee.

Capt. Albert H. Packard, of the 31st Maine Infantry, was the first officer buried in Mary Lee’s garden. Shot in the head during the second Wilderness Campaign, he survived long enough to die in the Washington hospital.

General Meigs sent crews to scour battlefields for unknown soldiers near Washington. Then he had soldiers excavate a huge pit at the end of Mrs. Lee’s garden, filled it with the remains of 2,111 nameless soldiers, and built a sarcophagus in their honor. Thus, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was created.

Meigs didn’t stop there. He built a Greek-style temple to George Washington and to Union Civil War generals by the garden and then had constructed a wisteria-draped amphitheater large enough to accommodate 5,000 people for ceremonies. He also built a massive red arch at the cemetery’s entrance to honor Gen. George B. McClellan, who remained popular with the troops but was combat ineffective. Of course, Meigs included his name on the arch.

Robert E. Lee lost hope of ever getting the property back. He and Mary moved to Lexington, Virginia, and he became the president of Washington University. He died in 1870. Mary Lee managed one final visit to the property in 1873. She died six months later.

Mary’s son, Custis Lee, sued in federal court in 1879 that the property was improperly seized. A jury found that the auction sale and the seizure of the property were illegal. The government appealed to the Supreme Court, where the justices ruled 5-4 that the 1864 tax sale had been unconstitutional and was therefore invalid.

The government had two choices, disinter nearly 30,000 graves and vacate the property or agree to buy it for a reasonable price. Lee was amenable to a sale and the federal government this time paid him $150,000 for the property. The government accepted the deed in 1883. Robert Todd Lincoln, Secretary of War and son of the president who so often was frustrated by Custis Lee’s father’s exploits on the battlefield, accepted the deed. The Civil War was finally over.

COMMENTS