The Battle of the Coral Sea Commences

Although the Allies had broken the Japanese codes and knew what their intentions were, countering them was another story. The Saratoga wasn’t in the Coral Sea but in Puget Sound undergoing repairs. And the aircraft carriers Enterprise and Hornet hadn’t returned from the Doolittle Raid. So, Nimitz dispatched the air groups of the USS Yorktown and Lexington.

The Yorktown Task Force 17 included the heavy cruisers Astoria, Chester, and Portland, six destroyers, and the tanker Neosho. The Lexington Task Force 11 consisted of the heavy cruisers Minneapolis and New Orleans and five destroyers.

On May 4, the Yorktown launched strikes on the Japanese forces that had invaded Tulagi. It irreparably damaged a destroyer, sunk three minesweepers, and four landing barges. Each side maneuvered toward the other unaware of the exact location of the opposing fleet.

The Japanese sighted the tanker Neosho, misidentifying it for an aircraft carrier, and the destroyer Sims. Twenty dive bombers scored seven direct hits turning the ship into a blazing inferno. She, nevertheless, managed to drift for four days until the surviving crew abandoned her and she was scuttled. The Sims took three direct bomb hits, two of which to the engine room. The keel buckled and the Sims sank quickly along with 379 members of her crew.

American scout planes had sighted several Japanese ships and Admiral Fletcher launched 93 aircraft in an attack of his own. Arriving at the presumed location of the enemy, they spotted the light carrier Shoho about 20 miles away. Shoho was blasted by 13 bombs and seven torpedo hits and was set hopelessly ablaze. Back on the Lexington, the radio room could hear the chatter of Lieutenant Commander Dixon of a Dauntless dive bomber squadron. “Scratch one flattop… Dixon to carrier, scratch one flattop.”

At midnight, the Japanese decided to postpone the invasion for two days.

Both Sides Bruise the Other

On May 8, the battle still raged. Each side launched carrier aircraft to attack the other. Pilots from Yorktown spotted the Japanese carrier Shokaku and hit her with two bombs just before 1100 hours. One penetrated the flight deck forward of the starboard bow and set fire to the fuel. The other hit aft. Although she could still receive aircraft, Shokaku couldn’t launch any.

The Japanese found the American fleet at 1118. Yorktown skillfully evaded eight torpedoes, but the dive bombers scored a direct hit which penetrated down to the fourth deck. Yet, she was able to continue with flight operations.

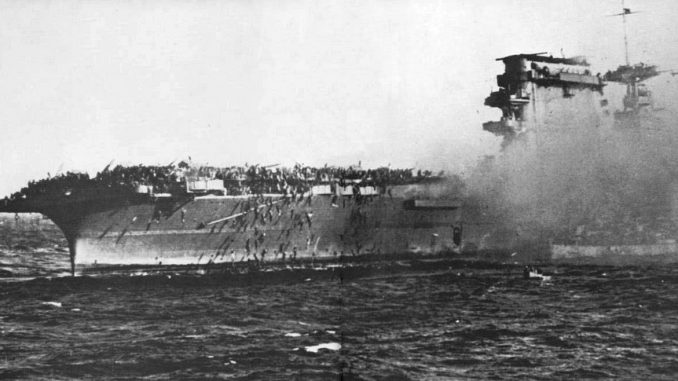

A torpedo hit Lexington at 1120 quickly followed by another. She was also hit by two small bombs. The hits from the torpedoes were handled by damage control parties and the listing of the ship was countered by shifting oil ballast. It appeared that she would live to fight another day and she began to receive returning aircraft.

However, at 1247 hours, a massive explosion shook the ship. Fuel vapors from a generator, which had been left running, ignited. Several other explosions followed. At 1445 hours, another massive explosion put the fires out of control. By 1710, the order was given to abandon ship. It was an orderly rescue and even the ship’s dog was saved. At 1956 hours the destroyer Phelps launched seven torpedoes to scuttle the Lexington and at 2000 hours she sank with a final explosion. The Battle of the Coral Sea was over.

The Aftermath of the Coral Sea and the Lead-up to Midway

Tactically, the battle was a victory for the Japanese. They had sunk the Lexington, Sims, and Neosho and had severely damaged Yorktown while only losing the light carrier Shoho and some smaller craft at Tulagi.

Strategically, however, it was an American victory. Without the aircraft carrier Shokaku able to launch supporting aircraft, and the heavy losses from the air groups of the Zuikaku, the invasion of Port Moresby was called off. Worse still, the damage to the two carriers kept them out of the upcoming Battle of Midway. On the other hand, Yorktown would limp back to Pearl Harbor and be repaired in time to fight in the upcoming battle.

The Allies had stopped the overconfident Japanese for the first time in the war. They didn’t attribute that the American fleet showing up at exactly the right place and time with two aircraft carriers was due to the Americans having broken their naval codes. They considered those to be unbreakable.

Yet, the next month at Midway, the same cryptoanalysis would lead to the Americans once again knowing the Japanese plan in advance. Because of that, Japan would suffer catastrophic losses that would turn the war’s tide.

COMMENTS