There are two principles that need to be mentioned. First and foremost, it’s a personal choice that every amputee makes whether or not they want to use prostheses and to what extent they are going to use them. There is no right or wrong choice in this arena. When the ultimate goal is a happy life, who can say what’s right for another person when it comes to their choice of personal transportation?

I will tell you that I choose full-time prosthetics usage mostly out of pure stubbornness/spite, and I had access to all the resources I needed to help me along the way. For amputees who didn’t lose their limbs in service to their country, but rather to a car accident or disease, the available prosthetic resources can be very different. But all hope is not lost. A civilian or non-combat-related military amputee has different constraints they must work within, but the resources are not completely absent. As a military retiree, I use the daunting VA system, but because I have a combat-related amputation, I can choose to go outside the VA system to have my prostheses made.

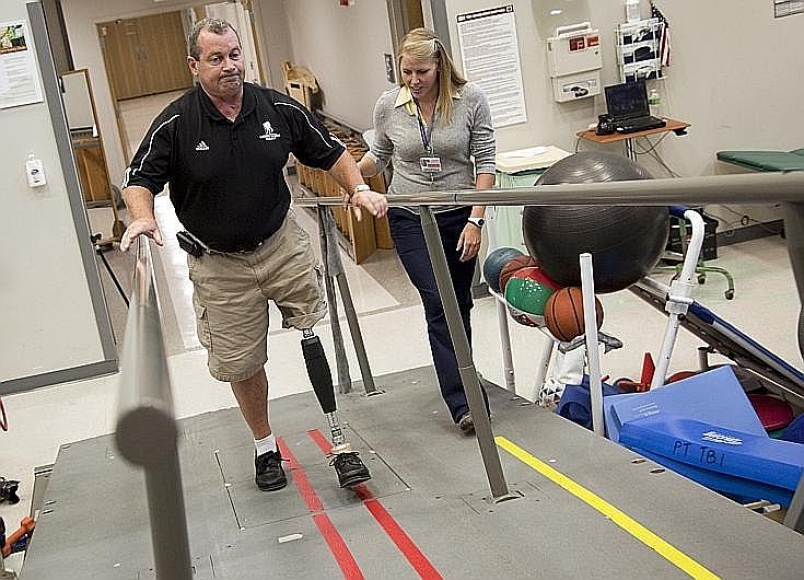

I have found a very skilled prosthetist (someone licensed to make prosthetics) in San Antonio, Texas by the name of Kirk Simendinger. He was my prosthetist while I was undergoing rehab at the military’s world-renowned Center for the Intrepid (CFI) at San Antonio Military Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas. I couldn’t have been happier when I heard Kirk had left the CFI and opened a private practice in San Antonio, making him easily accessible.

The second essential principle is that you cannot compare injured individuals to each other. It can be tempting to compare rehabilitation progress amongst below-the-knee amputees, or all above-the-knee amputees. But don’t do it. There is much more to an injury than what you may see on the outside. All above-the-knee amputees do not move through the recovery and rehab process at the same pace nor do they have the same goals.

Prosthetic Socket

The first time I put my on prostheses eight years ago, I had my hopes for a soft, cushiony, comfortable leg shattered with the reality of a cold piece of hard plastic. (Ironically, the light at the end of my tunnel during my early rehabilitation was receiving my prosthetic legs so I could get on with life. When I put on my legs for the first time, it became one of the lowest points in my mental struggle against depression.) A prosthetic socket is a device that must be made of a rigid material and must fit your newly amputated limb snuggly. The socket is placed over your amputated limb and connects to the other fancy prosthetic equipment like legs and arms. It was during those first few weeks, with the help of my wife, that I decided I was going to make those prostheses work. It was a decision made out of pure spite towards the prosthetics themselves, the two Afghans who detonated the IED under my vehicle, and my new amputee life that felt like a complete sh*t sandwich.

As I stated previously, a prosthetic socket is the device worn over the amputated limb. It is the most crucial part of the entire prosthesis because it is the interface between you and your prosthetic equipment. Unfortunately, it is also the most frequently screwed-up part of the prosthesis because it is dependent on your prosthetist’s skill and experience. When it is made incorrectly, it is uncomfortable, downright painful, can make your prosthetic leg/arm difficult to use, and can make you prone to falling.

A prosthetist once told me that his work is 60% science and 40% art. I have come to believe that’s true. There are scientific principles that are used in designing a prosthetic socket that must be followed to have a functional product. The basic principles dictate how the socket should fit and what basic shape it should have in order to provide the support and functionality it needs. If your prosthetist didn’t pay attention in school, your socket isn’t going to work out.

There is also the design part of the socket creation that takes the envisioned idea and makes it into a reality that can actually be worn on the body. The design process requires an artistic touch. There are two different techniques commonly used to create a prosthetic socket.

Hand casting: A plaster mold is used to recreate an exact replica of your amputated limb by wrapping your leg or arm in plaster, as if a cast was being made for a broken bone. The “cast” is then filled with a different plaster creating the exact replica of your limb. The prosthetist then “builds-in” all the details he wants in your prosthetic socket. For instance, he shapes the plaster by either adding or taking away material so the socket will fit just right. A special piece of plastic is then heated and formed to the plaster replica using a vacuum system. The process is called thermoforming, which uses the vacuum to ensure that the plastic is molded perfectly to the plaster before it cools and hardens. This method allows the prosthetist to use their expertise and make small changes to the plaster replica to account for areas that should be a little lighter or looser for functionality and comfort.

Computer-generated: An engineering software package is used to recreate the shape and size of your limb using a sensor that “scans” your leg. The prosthetist places grid points on your limb, and the grid points are imaged creating coordinates within the software. The prosthetist also places adjustment points on your limb, which are highlighted differently when they are uploaded within the software. The software allows the prosthetist to make changes to the virtual socket to account for any changes needed. The software recreation of your limb is then made into the actual product that you can wear.

There are pros and cons for each method. The hand-formed mold allows the experienced prosthetist to build his expertise into your socket by making subtle changes. But it also allows for more variability between prosthetists, and a prosthetist’s lack of expertise may also be very obvious using this method. The computer-generated mold has much less variability between prosthetist, is less labor intensive, but is also less customized to each patient because every patient starts with the same basic shape prior to the customization process.

Regardless of the method used, the end product is a test socket (Figure 1). The test socket is clear and made of a particular plastic that can be easily reshaped when heated. The amputee wears the test socket for a short period of time prior to the final socket being created. A prosthetic socket should be form-fitting and evenly distribute the patient’s weight over the entire surface area. The clearness of the plastic allows the prosthetist to exam the underlying material (which could be skin or a liner.)

Just like Goldilocks, the socket can’t be too tight, or too loose. If the socket is too tight, the muscles won’t be able to fully contract within the socket, causing weakness, unnecessary discomfort, and possible muscle loss. If the socket is too loose, the socket will fall off or rotate and twist around, allow too much friction between the limb and the socket, cause blisters and pain, and place too much weight on the bottom of the limb rather than distributing the weight around the whole prosthetic socket.

During the test phase, the socket is reheated to change not only the size and volume, but also the shape. The socket shouldn’t cut into the limb anywhere, so the test socket is easily adjustable. Once the amputee and the prosthetist are happy with the test socket, a final product is created.

The final socket is a carbon fiber product with a flexible inner section (Figure 2). It is more lightweight, stronger, and more comfortable than a test socket. The inner section of the socket in Figure 2 is flexible, giving increased comfort while still maintaining containment of the limb’s tissue. The hard carbon fiber outer section provides the rigidity that you need to be able to use the prosthetic limb.

This is crucial: The amputee should never feel pressured into accepting a prosthesis that they are not 100% comfortable with. In insurance terms, once a prosthesis has been given to the amputee and the acceptance forms have been signed, the patient owns the prosthesis, whether it fits or not. The insurance company will wash their hands and potentially deny future claims for a new prosthesis unless you can demonstrate that your prosthetic socket no longer fits properly due to your body’s changes.

There may be some wiggle room with Medicare and a few other insurance companies that give a six-week period to return the device after acceptance, but don’t rely on their forgiveness. If you feel like a prosthetist is trying to pressure you into accepting a prosthesis, don’t do it. Tell them “no thanks” and move on to someone else.

Like all sectors of medicine, there are people who care about their patients, and others who care about moving patients down the production line. If you’re the amputee, this is your limb, life, and comfort at stake. A poorly made socket will make your life miserable. The person who sold you the device doesn’t have to wear it or rely on it for their daily life. It doesn’t affect them. Trust me, I have been pressured and bullied into accepting pieces of crap that I never used. Try not to make my mistake.

Although the Veterans Administration doesn’t advertise it, if you are a combat-related amputee, they must allow you to see any outside prosthetist you want regardless of whether or not they are on the “approved list.” The VA will also pay for an amputee to travel to a good prosthetist if your region doesn’t have any.

Socket Suspension

A socket’s suspension is what holds the socket onto the limb. It is important to select the proper suspension system that takes into account body type, the normal changes that occur to an amputated limb through rehabilitation, the length and shape of the limb, skin condition, and physical ability or concurrent medical conditions. The suspension system must be selected prior to socket creation because the socket must be made specifically for the suspension method of your choosing. For simplicity, we will only briefly cover three main categories of suspension options: liners, direct suction (liner-less or skin suction), and external suspension (belts, compression sleeves, etc).

Liners

Within this category, there are many subcategories all based on an individual company’s proprietary product lines. The big decision to be made is whether the liner will use suction or mechanical attachment to hold the socket on the limb. Regardless of the attaching mechanism, liners are made of a comfortable, flexible material that is placed directly over the limb. A liner provides cushioning, skin protection against wear and tear, and a mechanism to account for the natural volume loss that occurs for the first couple years after becoming an amputee (as your limb gets smaller, a sock is placed over the liner to take up space—allowing your prosthesis to fit properly). A liner can also feel hot, confining, and add unwanted material between your body and the socket, decreasing the feeling of control and tactile feedback.

Liners made for a suction system (Figure 3) rely on a negative pressure environment, or vacuum, between the liner and socket to keep the socket from falling off. The liner is designed with a flexible outer ring that is able to create an air-tight seal within the socket. Air is pushed out of the socket through a resealable valve when the arm or leg in placed inside the socket. Once the valve is closed, the flexible ring on the liner creates an airtight seal. As the person wearing the prosthesis lifts their leg or arm up or off the ground, the airtight environment holds the prosthetic in place. A cotton sock is easily added behind the flexible rubber ring to take up space and keep an airtight seal if the amputated limb loses volume.

Non-suction liners rely on other mechanical devices to secure the prosthetic socket onto the liner. Most commonly used is a pin-and-lock system (Figure 4). A metal pin extends from the end of the liner, which locks directly into the bottom of the socket. A perfect fit is not needed between your limb and the socket in order to secure the prosthesis onto your body. The downside to both liner systems is that some people feel like the entire weight of the prosthesis is hanging from the very end of their limb.

Direct suction (liner-less)

There are a variety of terms for this system, but they all describe a prosthetic socket that is placed directly over a limb without a liner or any material between the two. Similar to the liner system, a suction or vacuum-like environment is used to hold the socket on the limb.

This direct-suction system can feel cooler than wearing a liner, and some users feel like it provides better tactile feedback. For instance, when stepping on a small object, that pressure change is translated directly into the limb rather than being absorbed by a liner or other cushioning material. The lack of cushioning can take time to get used to, can be uncomfortable for some by increasing the wear and tear on the user’s skin, and the system does not easy allow for volume adjustment.

There are a few easy ways to make direct-suction liners fit more snuggly if your limb size decreases, like placing foam between the carbon-fiber shell and flexible inner shell. Choosing to use a direct-suction system also assumes that your prosthetist is able to make it for you. It requires meticulous creation of your socket. There must be an airtight seal between your skin and the socket, while still being loose enough to be comfortable.

External suspension (belts, compression sleeves, etc) – Just as the name implies, this system relies on mechanical devices outside the socket to hold it in place. These can be used in conjunction with other suspension systems or alone. They can provide a feeling of security that your limb won’t fall off and potentially help create a more airtight environment for your suction suspension system to function in.

I personally use a direct-suction socket. I started out using the pin-and-lock liners followed by liners with a suction system. I have found that I like the direct-suction socket for comfort, biomechanical feedback, and temperature regulation (I always feel hot to begin with).

A direct-suction socket requires your amputated limb to have reached a stable size. There must be an airtight seal to hold the socket onto your limb, so the socket can’t be too loose. But if it’s too tight, the socket will be painful and ultimately non-functional because you won’t be able to contract your muscles properly to walk, which in turn could cause your muscles to atrophy. This means you need to have a prosthetist capable of making the socket properly, you need to maintain a certain body weight or limb size, and you have to train yourself to help hold the prosthesis in place.

Why you need to find a good prosthetist is fairly straightforward, but not always easy done. (As I wrote earlier, do not accept a prosthesis that doesn’t fit properly!) Early in the rehabilitation process, a new amputee will find that their limb’s size and shape may vary drastically from day to day, making a liner-based suspension system more favorable. As discussed earlier, some suspension systems are designed to account for a loss of limb size. None of the suspension systems can account for weight gain.

As your amputated limb matures, the size will become more stable. I have found that I have a five-pound range in body weight where my prostheses fit properly. If I lose too much weight, my legs want to fall off. If I gain too much weight, my legs are uncomfortable and start to cause skin breakdown and pain. To me, this means I have to watch what I eat. I can’t eat too many or too few calories, and I have to exercise on a regular basis. I also watch my sodium intake. Foods high in salt cause you to gain water weight. Just like a ring on your finger feels tight the day after eating a salty meal, my prostheses feel tight if I eat a meal high in salt.

Whatever your routine is, you need to maintain it. You can’t gain or lose a significant amount of weight unless you have a suspension system designed to accommodate your limb’s volume loss. As a direct-suction suspension user, I have also learned to help hold my legs on during certain activities. I personally like my prostheses a little on the looser side. This feels more comfortable to me, but it means I have to be mindful of them possibly coming off. Certain movements like sitting in a short or hard chair, or getting into a tall vehicle requires me to “hold” my prostheses on. I don’t hold them on with my hands, but rather by flexing or contracting the muscles of my legs inside the sockets. When I contract my leg muscles, they get bigger—holding my legs in place. I don’t even notice doing it anymore, nor could I tell you all the types of movements that require me to do it. I have trained myself to do it instinctually.

I have also found that my prostheses fit much better if I put them on twice. This means that I wake up in the morning prior to my workday and put my prostheses on as I normally would. I spend the next 45 minutes to an hour walking around, drinking coffee, et cetera. During this time, my legs are settling into my prostheses and the prostheses are warming up and becoming more pliable. Then, I take my prostheses off and put them back on. I find that the second time I put them on, they fit much better. I run into few issues and pain through my long workdays.

Although brief and high-level, my hope is that this article helps increase the knowledge of products and services available to amputees and their families. Remember, just because you have lost a limb or two doesn’t mean you have lost your life. Don’t allow poorly created prostheses to relegate you to a life of pain. Keep looking until you find a prosthetist who is willing to work with you and can make you prostheses that aren’t painful. The resources are out there.

COMMENTS