The Army Corps of Engineers arrived relatively quickly and set up specialized laser monitoring equipment to observe the building. While law enforcement was focused on an obvious crime scene, the fire department and subsequent Urban Search and Rescue teams were focused on finding and rescuing survivors. This particular bombing was unusual as well because of the vast size of the crime scene, primarily radiating out in a fan shape from the front of the building for blocks. In fact, from the back of the federal building, you could scarcely tell a massive explosion had nearly toppled the structure. Multiple buildings in front of the Murrah building were also heavily damaged, to include the Water Resources Board and Journal Record buildings, which sustained heavy blast damage and were found to contain valuable evidence from the rented Ryder truck that McVeigh and Nichols turned into a Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED).

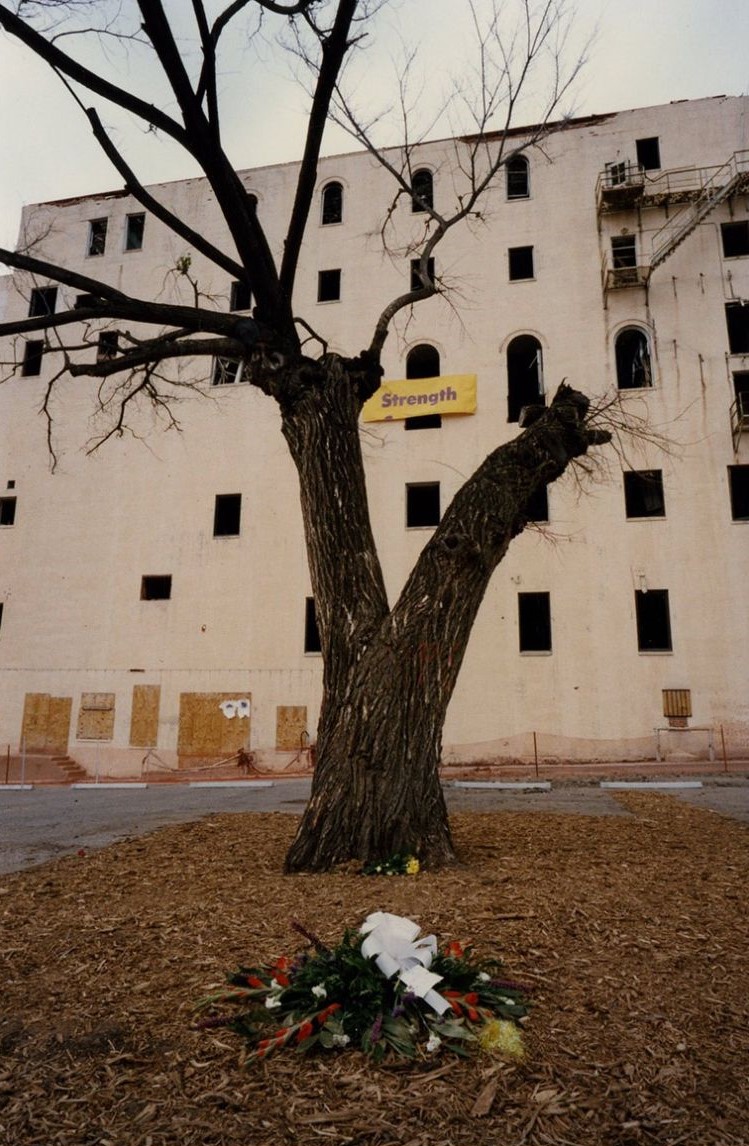

Between the Journal Record building and the bombing site, a lone tree survived, blasted almost completely free of leaves, and it is today part of the Oklahoma City National Memorial Museum. Although there was occasional tension as to competing mission priorities, after several days, when it became apparent no more survivors would be found alive, the problem abated. Any debris taken away had to be searched for potential evidence, and doing it all on scene was wildly impractical.

While the NRT set up selective evidence screening and sifting triage on scene, complete with screens to look for very small items of evidence, this was insufficient given the scores of tons of debris that needed to be screened. We decided to use dump trucks to take the debris to the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Department range, and methodically deposited it there in numbered piles for screening. It was this site where I was assigned to help lead screening operations. One agent, a Western NRT teammate, had a particularly macabre job: he was assigned to the coroner’s office, trying to match up various limbs and body parts to each other to find out just how many victims we actually had.

The Range

Because of the sheer volume of debris which needed to be carefully screened, and the recognition there was no place in the immediate vicinity of the Murrah building to do it, the Oklahoma County Sheriff’s Department range was chosen to deposit the debris and do search operations. The site was ideal because it was not too far from downtown Oklahoma City, had large amounts of open flat space, and could be access-controlled. In addition to the more typical sifting operations ATF and FBI do for most post blast investigation scenes (with literal wire screens set inside raised forms where you sift through dirt and debris), the massive amount of evidence prompted the use of some experimental technology in the form of a giant piece of mining equipment used to sift dirt for gold with massive amounts of water.

This “hydro-sifter” was a great idea in theory, but in application, it was really primarily designed to be able to go through lightly rocky soil, and proved to be ill-suited for screening chunks of concrete, pieces of automobiles, and other building detritus. The giant and noisy machine regularly broke, and made a godawful mess with the dirt, covering the operators in mud at the end of the day. A Los Angeles-based special agent bomb technician friend of mine from the FBI, Kevin, was assigned to supervise the contraption, and by the end of the day, he was at times unrecognizable because of the mud.

Help in conducting the searches was not a problem, as every law enforcement agency and fire department wanted to help. Unfortunately, having too many hands proved not to be terribly useful, as they were not trained in post-blast investigation, and thus were really not sure what to look for. Ultimately, we settled upon taking help primarily from Federal agencies, particularly those that had offices in the destroyed Murrah Federal Building. Every day, a small group of new volunteers arrived, enthusiastic to be part of the team.

As we would work our assigned mounds each day, we would often have to stop work to document specific kinds of findings, particularly human remains, and potential evidence I would be called upon to examine to give my opinion as to whether or not it was part of the truck, or even seized law enforcement evidence. Something rarely discussed in stories coming out of the blast was the fact evidence vaults of multiple federal law enforcement agencies were damaged or destroyed, and the evidence necessary for ongoing federal cases was in fact scattered in the debris remaining at the federal building, as well as in the piles before us. Ranging from cashier’s checks to cocaine, and machineguns to marijuana, these were items of particular interest to us, and when they were found they were photographed by agents from the relevant agencies and collected for safe storage.

We had related problems at the Murrah Federal Building blast site, when inert ATF explosives props were spotted in the debris, causing all work to stop. Some conspiracy-minded individuals who know zero about explosives later spun that into tales of internal building detonations and illegal storage of live explosives in the federal building, but it is a losing proposition to reason with people who wear tinfoil hats.

After a few days at the range, my ATF colleagues and I noticed a particular trend. Young agents would arrive in the morning, practically tearing at the piles with their bare hands to get the job done. As we would find human remains and key evidence, they would gradually slow down, becoming withdrawn. I remember one young agent from a small federal law enforcement contingent uncovering what proved to be a child’s forearm, almost completely intact, and he shut down then and there. We gently took him aside to relax and de-stress. He was not the same for the rest of the day, and we never saw him again.

Similarly, I remember finding a DEA agent’s badge and credentials one day; I never did learn if it belonged to the DEA agent who was killed or was rather from an agent who had left credentials in their desk. Eventually, chaplains, peer support teams, and social workers set up at the scene in the event people needed or wanted to talk, and we held occasional stand downs for people to gather and process what they were seeing.

About a week into the range sifting and screening operation, the U.S. Army, answering our call for federal resources that could help us rake down and sift the piles so they were more manageable in size, sent about a platoon’s worth of soldiers to assist us. One day, a young PFC flagged me down because he thought one of the parking meters in the debris – and there were many – appeared “funny” to him. When I looked at the item, I immediately recognized the gears and shape as something that would have had to have come from the Ryder truck VBIED, in particular an axle half shaft, which must have been blasted into the building like a missile from the force of the explosion. With his help, I dragged the item off to the evidence recovery truck, where I filled out a rudimentary evidence tag. I would not see it again until 1997, when I flew to Denver, Colorado to participate in trial prep for McVeigh and Nichols.

R & R. Sort of

Because our shifts were long and both physically and mentally draining, our chief activity after getting cleaned up, calling home, and eating was to start drinking. Perhaps not the best way to cope, but for those in the thick of really ugly things, it was common then. There were no really good gym facilities close by to use for a workout, and most people were frankly too mentally and physically exhausted to try anyway. The Embassy Suites, as part of their desire to be extra hospitable to front line personnel, kept expanding the manager’s reception hours so that it became, in effect, an hours long open bar.

Not long before our team wrapped up and redeployed home, some of my agency’s senior management thought it would be a good idea to have an “all hands” meeting in one of the large hotel conference rooms to thank all of us in person and answer questions. Well over 100 ATF personnel were present, along with a number of other federal agents from different agencies who were drinking with us. It was a great idea until it wasn’t. Unfortunately, the meeting was scheduled to kick off deep into the evening’s drinking fest. Everything started out well enough, with appropriate laudatory comments from the visiting brass. A number of agents asked why [ATF Headquarters] was so reticent to get out in front of the media to highlight ATF’s great work, the frankly amazing and cathartic visits with area school kids, and skill of the NRT in particular.

One of the well lubricated agents, a veteran of the 1993 Branch Davidian raid and standoff in Waco, Texas, which resulted in the deaths of four ATF agents, asked pointedly why headquarters was again letting the street agents down instead of sticking up for us. At this point the senior executive, himself associated with the tragic events of Waco, responded by accusing the agent of being one of “you people” who failed to support management by speaking to sources outside of ATF, instead of keeping everything internal in the aftermath of Waco. The room fairly erupted. Agents began standing up, shouting and pointing at the clueless senior executive, who began to stammer and physically backpedal. Fortunately, a well-respected agent stepped in to diffuse the situation, and the visiting executive beat a hasty retreat for the exit, leaving our non-ATF federal agent friends in the crowd wide-eyed in disbelief.

The Aftermath

In February 2016, I was part of ATF’s “All-Senior Executive Service” conference in Oklahoma City. Ironically, I had started a new job as Deputy Director of the Terrorist Explosive Device Analytical Center a month prior. Co-leading the U.S. government’s sole strategic facility for the exploitation of terrorist explosive devices of interest to the United States, I was now going (back) to the scene of the worst terrorist bombing ever committed on U.S. soil. It felt otherworldly.

A highlight of the management conference was a specially guided and narrated tour of the Oklahoma City National Memorial Museum. It was like stepping back into a giant time capsule, and it was the first time I had been to Oklahoma City since the bombing. It was frankly eerie to see so many artifacts from the bombing, the subsequent trials, and walk the same ground, which was hard to recognize with the Murrah Federal Building gone and the passage of 20-plus years.

If you have not seen this museum, it is incredibly well done and reminds me of the 9/11 Memorial and Museum. You should make it a point to see both. Finally, in May 2024, at an ATF retiree’s association meeting, I bid on and won a very special engraved piece of granite that was rescued from the remnants of the Murrah Federal Building when it was demolished in 1995. I see it every day in my home office and it serves a reminder of 30 years ago, not just of man’s inhumanity to man, but more importantly of the incredible generosity and resilience of the people of Oklahoma, who rallied to overcome the evil that was visited upon them that late spring morning.

COMMENTS