This article was co-authored by Deacon David P., Society of Jesus, who will be ordained as a Jesuit priest in the summer of 2018. Deacon David attended Fordham and Santa Clara University, where he received degrees in psychology, philosophy, and theology. David also happens to be the first cousin of Frumentarius, which, per Catholic doctrine, secures Fru’s place in heaven. At least, Fru is pretty sure that’s how it works… more research might be needed.

March 19, 1945. The USS Franklin is conducting offensive operations off the coast of Japan in the waning days of the Second World War. The Navy vessel comes under withering attack by Japanese aircraft, including a kamikaze attack which inflicts a devastating and direct hit on the warship. Lieutenant Commander Joseph Timothy O’Callahan, military chaplain and Catholic Jesuit priest, begins to grope his way through smoke-filled passageways to the flight deck above. In the midst of exploding armaments, and with the ship hit by incessant explosions, O’Callahan ministers to the wounded and dying, “comforting and encouraging men of all faiths,” according to the citation that would result in the Jesuit priest receiving the Medal of Honor.

Realizing there was more to be done beyond his spiritual duties, O’Callahan then “organized and led firefighting crews into the blazing inferno on the flight deck.” He directed the sailors to jettison live ammunition and to flood the magazine in which live ordinance risked being detonated.

O’Callahan personally manned a firehose to put cooling water on hot, armed bombs rolling hazardously back and forth on the deck of the listing naval vessel. According to his citation, Lt. Cmdr. O’Callahan “inspired the gallant officers and men of the Franklin to fight heroically and with profound faith in the face of almost certain death and to return their stricken ship to port.”

O’Callahan was the first chaplain of any denomination and within any branch of the U.S. military to receive the nation’s highest military award for valor. It was not because he was a Jesuit priest that O’Callahan showed such courage and clear-headedness in the face of such terrifying conditions, but that fact no doubt played a significant part in influencing the priest’s actions on that day.

The Society of Jesus

Saint Ignatius of Loyola, a Basque born in Spain, founded the Jesuit order (officially known as the Society of Jesus) following the time he spent in service to the military of the kingdom of Castile. While leading an infantry company in the Battle of Pamplona, Ignatius was wounded in the leg by a cannon ball and would walk with a limp for the rest of his life. During his long and painful recovery, as he lay in a bed nursing his injuries, Ignatius reportedly had a religious experience which ultimately led him to found the Jesuit order.

Not only did his military experience directly lead to his founding the Jesuits, it also influenced Ignatius’ vision for the organization of the order. In the 16th century document which serves as a sort of “warning order” for would-be Jesuits, Ignatius wrote:

Whosoever desires to serve as a solider of God beneath the banner of the Cross in our Society… is a member of a Society founded chiefly for this purpose: to strive especially for the defense and propagation of the faith and for the progress of souls in Christian life and doctrine[.]”

The Bible is full of imagery depicting the world as a battlefield upon which good and evil clash, and Ignatius picked up on these images and used them both in his own prayers and in the prayers he suggested for others within the order. In one such prayer, called the “Prayer of the Two Standards” — referring to the battle flags that armies flew at the time — Ignatius asked Jesuits to consider under which standard they would fight — good or evil.

Furthermore, Ignatius referred to Jesus himself as the “sovereign Commander-in-Chief of all the good,” framing his newfound order as a platoon of warriors meant to engage in spiritual warfare on behalf of the forces of good. He also put this doctrine into practice by going directly to the Pope at the time and stating that whatever needed to be done for the Catholic Church, he and his Jesuits were available to do it. He was positioning the order as the Pope’s own Special Missions Unit, a strategic-level mission force akin to today’s Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

Given that the Jesuits’ original mission was to insert into a particularly troubled locale, assess the situation, solve whatever problems needed solving, and then redeploy to the next challenge, it is sometimes said that Ignatius founded the Jesuits as the “light cavalry” of the Church. And if you have not heard enough military metaphors, Time magazine also referred to the order as “the Pope’s Marines,” due to its emphasis on availability for rapid deployment.

Fast forward roughly 400 years, and as has been the case with most of the world’s military units, mission creep set in and the amount, scope, and duration of the taskings handed down to the Jesuits greatly expanded. Thus, the Jesuits have transformed over time from a “light cavalry” to more of a “heavy artillery.” However, the ideal of availability to go wherever they are needed — at a moment’s notice — remains strong in the order, and Jesuit priests to this day still take a special vow to undertake any assignment given to them by the Pope.

In addition to this vow, the Jesuits undergo extensive training and schooling before they are able to call themselves full members of the order. Because their assignments are so varied, Ignatius wanted all of the Jesuits to undergo long and thorough training, to be ready for whatever was asked of them, which included substantial training in languages, philosophy, and theology.

This extensive training and education led the order to provide education to common people all over the settled world starting in the 16th century. The order earned the nickname “the schoolmasters of Europe” as a result, and were also heavily engaged in missionary work as part of the Age of Exploration. They thus deployed to the “unsettled” and unknown (to the West) frontiers of the globe as well, explaining and spreading Catholicism to people who had never heard of Christianity before, and translating it into cultural terms they could appreciate.

One could thus nickname them the “Special Forces” of the Catholic church, as well. Their mission was almost a form of (spiritual) Foreign Internal Defense (S-FID), as they embedded themselves in these strange lands, and worked to advance the church’s interests (i.e., religious education and conversion). The order performed a similar mission within Native American communities in the 19th century United States.

This insertion into “hostile territories” was nothing new for the Jesuits. During the Reformation, a number infiltrated into countries whose governments were hostile to Catholicism at the time, such as England. There, they ministered to those who wanted to remain Catholic. This tradition of underground ministry would continue into the modern era, as men like Father Walter Ciszek operated in Soviet Russia from 1939-1963, during which period he spent time as a KGB prisoner in Lubyanka prison.

This modus operandi of ‘secret ministry’ led to the Jesuits earning a reputation for political intrigue and subversiveness. One of the most famous examples of this phenomenon was Edmund Campion, who fled England after becoming Catholic, but later returned as a Jesuit and secretly ministered to the people there until his capture, torture, and death.

In a fascinating bit of “DaVicini Code”-esque conspiracy theory, there is a hint of this secret ministry M.O. in the James Bond film “Skyfall.” Near the end of the movie, as the groundskeeper is showing “M” around the old Bond family home, he notes a place that he calls a “priest hole.” These were hiding places installed in the homes of wealthy (but secret) Catholics of the time in which the priests hid from the authorities.

One of the main builders of priest holes was a Jesuit named Nicholas Owen, who was also a skilled carpenter. When the English government finally caught Owen, they knew that he could tell them about the network of hiding places he had built, and tortured him in the hopes that he would give up the locations. He refused and, like Campion, he was tortured to death. Whether the priest hole in the Bond ancestral mansion was supposed to have been built by Brother Owen or not, at some point in the 1500s, James Bond’s (fictional) ancestors helped Jesuit priests in their underground ministry.

So just what does a “typical” Jesuit training cycle look like? What is the pipeline through which these men travel to become a Jesuit? The training is longer than for any other order in the Catholic Church, and usually takes between 11 and 13 years before a man is a full Jesuit priest. The breakdown of the different training blocks follows below:

Novitiate

This is the two-year “boot camp” for religious orders. Each order of priests has a novitiate, though for most other orders, it lasts only one year. During this time, one is a “novice,” and lives under the close supervision of a priest called the Master of Novices. Like a military boot camp, a novice can expect to ask permission for just about everything short of using the restroom.

In between classroom time and learning about prayer and how things work in the order, a novice is also sent out for hands-on experiences for several months at a time. As an example, the assignments undertaken by the co-author of this article, Deacon David, included working as an orderly at the Jesuit retirement center in New Orleans, as a chaplain in a juvenile detention facility on the Texas-Mexico border, and working at a parish in Belize City, where he mostly taught remedial reading to 2nd and 3rd graders.

At the end of this time, a novice makes his first vows and progresses from being a “Jesuit novice” to simply, a ”Jesuit.”

First Studies

This two-to-four year block involves learning how to live as a Jesuit, including under the vows that each man takes. Every Jesuit must also undertake two years of philosophy studies, which form the backbone of intellectual arguments surrounding religion and have thus been used from day one by the Catholic church to facilitate discussions of theology. The study of philosophy also sharpens a Jesuit’s mind and gives him the tools he needs to talk about life’s big questions with people who may not believe in Catholic scripture, or for that matter, in any kind of supreme being at all.

During this time, the Jesuits will often undertake other studies as well, especially in languages and other areas deemed potentially helpful for their future work. This co-author was asked to acquire a Bachelor’s of Science in Psychology, which has turned out to be incredibly helpful when people come to him for advice (spiritual or otherwise).

A friend of the co-author’s, furthermore, was asked to earn a degree in Statistics during this time, in preparation for further studies in Economics. Additional areas might include the Classics, Chemistry, Literature, the Law, et cetera. For example, the most famous living Jesuit — Pope Francis — has a degree in Chemistry and was a high school chemistry teacher during his regency phase.

This is a time period in which a Jesuit’s interests and talents are identified and he is given some of the basic tools he will need academically and professionally to do whatever he might need to do for the order and for the church.

Regency

One unique aspect of Jesuit training, and one reason that it takes so long, is that from the first day, time is divided between the classroom, the chapel, and the outside world. Regency is the three-year period during which one first experiences full-time work as a Jesuit, as opposed to merely a few months of “temporary duty.”

During this phase most Jesuits teach at a high school, which is usually all-male and Catholic-run. Most Jesuits would consider this phase, and teaching high school, to be a challenge. Unofficially, each has a large number of collateral duties in addition to their teaching roles. This co-author, for example, was the assistant theatre director (mostly in charge of set construction), and also taught ethics to juniors (fun because they could think) and scripture to sophomores (fun because they couldn’t).

The time is also highly-rewarding for the Jesuits, as they deal with teenagers and all of their associated issues, and find their footing as spiritual advisors. They bond and grow with their charges, during events like “World Youth Day,” which this co-author was lucky enough to attend in Rio de Janeiro with five Jesuits and 40 students.

Theology

This is the final stage of academic training, and lasts three to four years. Unlike the first round of studies, it is much more focused. There are courses in the Bible, church history, ethics, as well as practical classes like how to preach.

At the start of his third year, a Jesuit is ordained as a “deacon” and assigned to work part-time in a local church while continuing as a full-time student. At the end of this phase, a Jesuit is ordained as a full “priest.” Subsequently, any further studies are simply for whatever particular assignment one might have coming up, but most often a Jesuit will be sent to work first in a parish and then somewhere more long-term.

Approximately five years after completing training, a Jesuit will be invited to make final vows in the order, which is the point at which priests will take the vow to go on any mission given to them by the Pope. Ultimately, that is what being a Jesuit is all about, and what all those years of training lead to: a maximum freedom and availability to do what needs to be done as a soldier of God beneath the banner of the Cross, and doing what one can for the side of good in the fight between good and evil that exists in the world.

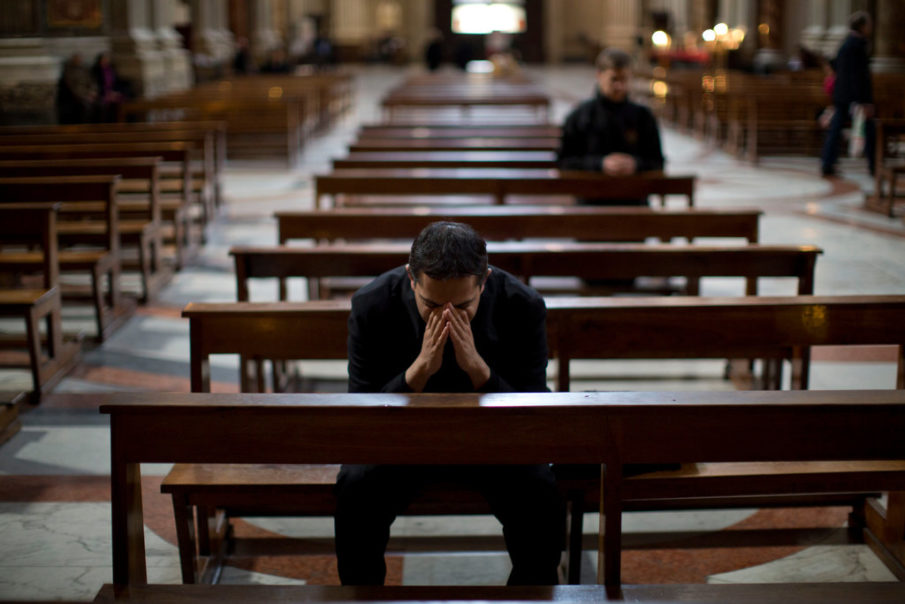

(Featured image by Emilio Morenatti/Associated Press).

COMMENTS