The assault ODA was ready to move. They dissolved into the dark tamarisks. They moved to a position about a klick from the runway of the naval air station, opposite the submarine-detection station, and put eyes on the target for the next 48 hours. At H-hour they would move into a position just inside the tree line close to the runway and wait for the assault window to open.

The next morning we, the “Spetsnaz” Harassment and Interdiction (HI) ODA, spooled into action. We split into two-man teams. My bud and I went to the motor pool and begged a heavy set of bolt cutters for “half an hour, to cut a lock on our gate.” With bolt cutters in hand, we left a pre-printed note on the front desk with a statement to the effect of, “This is a MARDEZ exercise. Your bolt cutters will be in use by U.S. Army 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), and will be returned in approximately one week.”

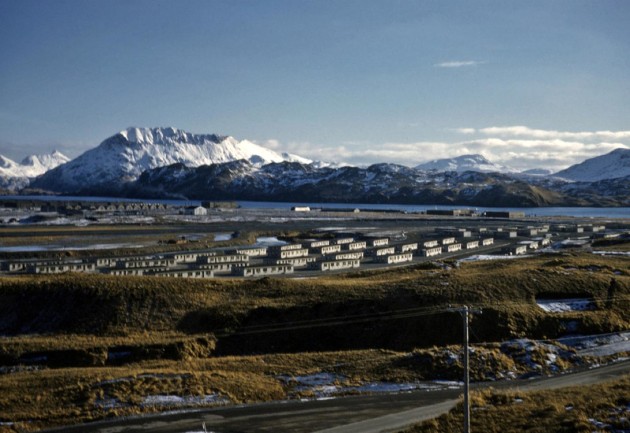

We used the bolt cutters to wreak our havoc. Locks were cut, gates thrown open, and buildings opened up all over the air station. Each case required a naval security force response and investigation. During the night hours, some of the teams conducted drive-by shootings with blanks from assault rifles on rock and roll. Each time naval security was called to investigate. Security forces on Adak were getting overwhelmed; they had to remind themselve continuously that this was just (supposed to be) and exercise.

Time for a bogus bomb threat at the club!

My bud and I entered the club, me with my bad mood and him with a day bag. He took the day bag and found an empty table, then withdrew an ammunition can with an alarm clock inside set to ring within the hour. He placed it under his table, then consumed a beverage to anchor his reason for being there.

I sat at the bar and nursed an ice tea. Conversation at the bar focused on the numerous recent security breeches taking place on the station. Speculation of who the culprit was and why they were harassing the station were astronomically absurd. There was palpable paranoia and perhaps even a touch of pandemonium. People were seeing flying saucers, Jimmy Hoffe, Elvis, and unicorns.

I spied a brother GB team sitting at a table with a female who, I later found out, worked in an FM radio station right there on Adak NAS. They played music, conducted interviews, broadcasted news and current events. They were trying to “recruit” her as an inside asset to allow them to force entry into the studio to interrupt the normal broadcast with a pre-recorded tape of communist propaganda. I felt they were taking a huge risk, but then I was getting ready to “bomb” the nightclub, so I mean… well, you know.

I departed the club, with my bud not far behind me carrying his empty knapsack. I stepped onto the bus that was waiting to take club patrons back to dormitories when the club closed. By bud moved up the road on foot to find a telephone to call in the bomb threat. Minutes later, the building ejected its crowd, which swarmed toward warmth of the bus.

Club patrons climbed into the bus spewing oaths and profanity. One female was crying, partly because she was tipsy, but mostly because she had left her purse on a table in the club. The bus departed and spread its agitated cargo throughout the housing sector. Security had responded in force to the club along with a Navy Explosive Ordnance Disposal (EOD) unit. EOD had not found the ammunition can. Instead, they took the woman’s purse left on the table and put it under great scrutiny. They put an explosive charge on her purse and blew it up in place. Moments later, the alarm clock in the ammo can sounded. Fail!

Were we going too far? Not yet, but we would the next day. The purse incident was Saturday night. The next morning, a team had taken the ol’ alarm-clock-in-an-ammo-can with them to church. They put it under a pew and left. The alarm clock went off during mass. This time the air station commander wanted heads, but to get the heads you had to first find the heads. Our heads were moving at night and under cover. I had a completeNavy Seabee

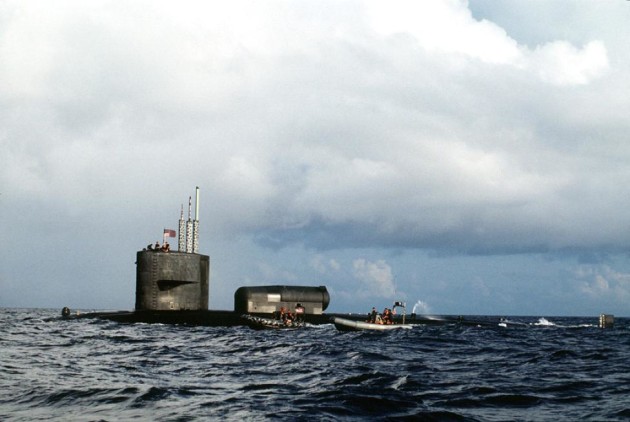

We were ordered by our team commander to stand down the harassment and interdiction (HI) for the rest of the day, but that night the Dreager dive on the dock was still a “go”. We would have a healthy support staff since the rest of the guys were suddenly with nothing to do. A small group was considering a search for the assault ODA in the woods, as they had missed all of their scheduled radio contacts. The assault just seemed to be doomed from the very beginning.

We donned our PolyPro undergarments, dry suits, LAR Vs, and Secumar inflation vests beginning at 2300 hours that evening. We were photographed just prior to climbing aboard a van that would drive us to our debarkation point.

A topographical map reconnaissance and subsequent drive-by in a vehicle revealed a draw that began very close to the shoulder of the paved road, and led 30 feet down to the water’s edge. The target dock was approximately 1000 meters from the bottom of the draw. Movement through the heavily vegetated draw in full dive kit would be arduous, but concealed.

In the photo below I am holding a compass board; its white lanyard tied to my left wrist. I would be leading the swim to the dock. My Team Sergeant Mark “Buck” B, our Senior Engineer Randy “Triple-R” Woolen (KIA), and I would be fastened together by a “buddy line” and would maintain a depth of no more than 33 feet of seawater. On the compass board is a Richie Ball compass, a depth gage, and the faint glow of a green chemlite. My sole focus would be depth, direction, and the pressure on my ears. I focused mainly on the compass. If I felt pressure on my ears telling me I was on a depth excursion, I would glance at the depth gage and adjust back to tactical depth. If my ears “popped” indicating I was rising, I would glance and adjust.

We made the awful descent down the draw. I drew my bearing to the dock with my compass, and we slipped into the water. No noise, no bubbles, no troubles. I sank us to about 30 feet and pointed us toward the dock. We finned vigorously to warm up. I felt I had maintained our heading accurately, but something didn’t seem quite right. It was taking us too long to get to the dock. Time for a halt and a tactical peek. I slipped to the surface and looked forward. Nothing! I looked behind me and there, at about 100 meters, was the dock with one guard patrolling its length, an M-14 rifle slung over his shoulder. It was so dark down there, we swam right between the pylons of the pier. I brought Mark and Randy up to the surface and we crept toward the nearest pier.

Again, we submerged to 30 feet. Randy was carrying a simulated explosive charge about 12 inches square by six inches thick. It had a written statement on it to the effect of, “This dock has been explosively rendered unserviceable by the 1st Special Forces Group.” I had taken it a step further, drawing the upper body of a troop wearing a Green Beret, a huge shit-eating grin on his face, holding up a Claymore clacker in his right hand.

Buck signaled us to ascend to the surface. I tried to rise but my buddy line to Randy was snagged. I unhooked it from my waist and came to the surface. “Where’s Triple-R?” Buck whispered. “My God, I was snagged down there; Randy must be too.” We immediately sank down, following the pier until we found Randy. In the mire of the near total darness he had been inadvertently tied to the pier with the charge. Buck and I instantly drew leg knives and cut him free. We double-checked that the charge was still secured to the pier and set off on a back azimuth for the draw.

I offset my azimuth to the left of the draw, so that when we hit shore we would know the draw was to our right. An expectation to hit dead on the draw was unrealistic, and to not know which direction the draw was could become a navigation nightmare.

Buck and I were still hooked into the buddy line. Randy kept his left hand on my Secumar vest and we swam back to shore. Despite my left offset, we smacked the draw almost in the center; it happens. We made the painful climb back up the draw and waited sweating in the vegetation. Our van appeared and flashed headlights three times (Morse Code letter “s” […]) on approach to let us know it was our ride. It stopped next to the draw and we piled in. Enough for a day…and a night.

The following day was D-day. H-hour was scheduled for 2300 hours, and we still had not heard a peep from the assault ODA. As the day wore on, we postulated that we would have to carry on as if the assault force, though incommunicado, would be at the right place and at the right time. Our ODA had put together a search patrol to locate the assault ODA once the Station Commander called off our aggression. The patrol completed a complex search strategy, but found nothing. In a way, there was a measure of comfort in the notion that if we couldn’t find them, the Station security forces certainly could not.

At 2230 hours, our cars and van eased closer to our assigned objectives. There were several support corollaries on two sides of the Quonset-shaped submarine detection building. Each had armed roving guards that would have to be neutralized at the stroke of 2300 hours. We were all armed with blank-fire (don’t envy us) concealed pistols.

At H minus five minutes, most of us quietly departed our vehicles and started inching the last few feet to close with our targets. My target was at the end of the detection building that faced the runway. I had not seen him yet, but there was supposed to be a guard there.

And then it happened. The clock struck 2300. I hooked around the corner of the fence and, low and behold, there stood my guard with his M-14 rifle slung. I already heard the cracks of the blanks being fired by my mates taking out guards at the corollaries. “Halt!” the guard demanded. I unleashed four caps at the startled guard and ran past him to clear the far side of the fence.

I heard the muddled asynchronous staccato beat of trampling boots behind me. I turned and saw in the faint glow of runway lights a whole can of whoop ass headed my way. The assault force was in a wedge formation and quick-timing it across the runway. They were on time, on target, and pissed off from their miserable stay in the tamarisks.

I took cover, because under the circumstances, I was as much a target as anyone else. The runway side of the door to the Quonset opened wide and several men rushed out to see what was going on. The assault force was already at the chain-link fence surrounding the Quonset, prepared to breach the gate.

One badass carrying a simulated satchel charge saw the door open. He wound up and slung the satchel over the fence. The charge smacked the floor hard just inside the threshold and slid down the hallway.

The assault ODA had already flooded through the Quonset and re-engaged guards that had refused to play the game and lay down. I witnessed a guard grab one of the hard, pipe-hitting Green Berets by his web gear in an attempt to detain him. Really? The GB put both hands behind the guard’s head, pulled his head down hard toward the ground and kneed him squarely in the face. The guard crumpled like a sack of kneed-in-the-face potatoes.

The assault force retrograded across the runway exploiting fire superiority with their bounding overwatch, and disappeared into the wall of vegetation. As I sprinted for my car, I heard screeching tires as my buds sped away and security trucks skidded onto the scene. As I got in my car, a patrol truck locked his brakes on my side of the vehicle and the driver and passenger lunged for my door.

This is why I left the window down before I departed my vehicle. Pistol still in hand, I emptied the magazine into the horrified faces of two sitting ducks. Shame on them for showing up to a gunfight with, well… no gun! I drove away gently and slowly, looking like I was just coming home from the grocery store. A few more patrol trucks whizzed by me. I turned on the FM radio and enjoyed my drive back to our safe house with serenades of late-night jazz from Radio Adak.

We flew back to McChord Air Force Base in a MC-130. The naval air station commander still had a sour taste in his mouth over some of our HI techniques, but you know if you send a Green Beret on a mission with no guidance, he will create his own “guidance” and improvise until he gets the job done. “In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king.” It had been amusing to be a Spetsnaz operator for a week, and yes, I returned the bolt cutters to the motor pool before I left.

Geo sends.

This article previously published on SOFREP 10.13.2015

COMMENTS