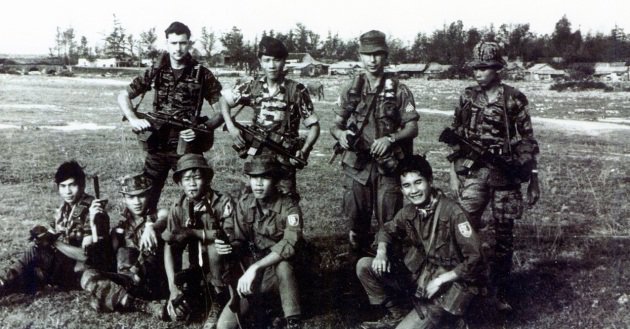

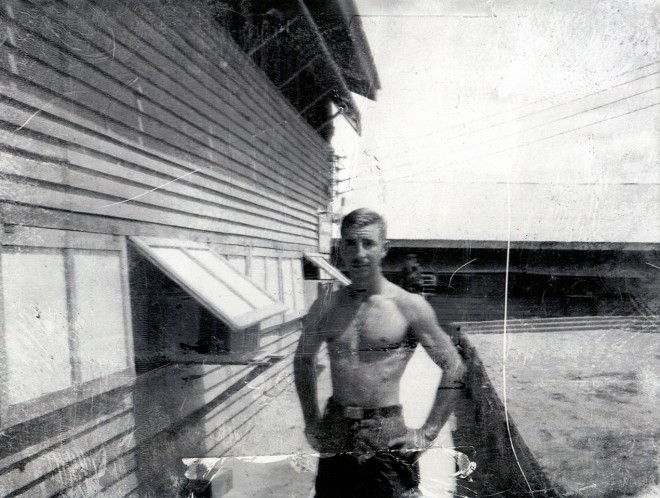

I knew all three of those Green Berets. Wald and Brown had served with me at FOB 1 in Phu Bai during 1968. When I returned for my second tour of duty assigned to CCN, I met Shue and was duly impressed with his quick humor and handsome good looks, He could have been a poster boy for the Green Berets in 1969.

Instead, like all of us, he, Wald and Brown chose to work in complete secrecy.

Even the official name of our unit was cloaked in the secrecy of bureaucratese: Military Assistance Command-Vietnam Studies and Observations Group — or SOG, as we knew it.

Because our missions were top secret, and because we had signed agreements with the government promising not to talk or write about SOG for 20 years, I knew that I couldn’t go home and tell Wald, Brown or Shue’s parents what had really happened to their sons, or where they were actually killed nor that they served on mission that generated the highest casualty rate during the Vietnam War, exceeding 100 percent casualties, including men killed in action and wounded in action more than once. (Some SOG veterans received seven Purple Hearts during their tours of duty in SOG.)

Compounding that gnawing frustration was the knowledge that if I was killed in Laos, my family would be kept in the dark. And, if our reconnaissance team had a successful mission, I couldn’t sit down and tell my folks about how we wire-tapped enemy phone lines, placed Air Force sensors along jungle trails and roads to monitor enemy movement or killed enemy troops during brutal battles deep in the jungles of Laos, Cambodia or North Vietnam.

The large majority of men who volunteered to serve in Special Forces did so knowing they would live in a secret world where simply knowing about a successful mission was one’s reward. There would be no bragging rights. There was no phalanx of media to tell our story.

It was Special Forces, operating in the dark, far away from public knowledge and snoopy reporters.

This was the method of operation for the Quiet Professions.

Since the Laotian farmer found the remains, the first of the trio of KIA Green Berets to return home was Shue. On April 29, 2011, a flag-draped casket rolled down a cargo ramp underneath the Delta Airlines jet that flew Sergeant Shue’s remains from Hawaii to Charlotte. The casket was greeted by a Special Forces honor guard, Green Berets he had served with in Vietnam and Shue’s family members.

Brown’s remains were returned to the United States in September.

Wald’s remains will return from Hawaii this week.

The trio of fated Green Berets are scheduled for burial at Arlington National Cemetery Thursday Aug. 30, with full military honors.

There will be at least a dozen Green Berets who served with Wald, Brown and Shue, including Maj. Gen. Eldon Bargewell. Bargewell ran at least one mission with Wald in 1968. Thursday, Bargewell will be representing the Special Operations Association, which was formed by the Green Berets who ran top secret missions for SOG during the eight-year secret war.

This service will also provide closure the Navy veteran Michael Buetow, who is the son of Wald. Buetow never met Wald, but knew of him and grew up only knowing the tiny fragments of information that his mother had heard through secondary information. Also, Mike Buetow’s son Gunther Buetow is presently serving in the Army. It was unclear whether or not he would be able to leave his assignment for the memorial service.

In addition, Wald’s half-sister, Frau Heike Deucker is flying in from Germany to attend the service, according to government spokesmen. Wald’s parents divorced in the ‘60s and moved to Germany. Thus Deucker will have closure for the half-brother she never met.

To the men who fought in the secret war, we are grateful that Wald, Brown and Shue are home.

But we are also reminded that there are still more than 50 Green Berets assigned to SOG who fought in the secret war in Laos, Cambodia and North Vietnam and remain listed as missing in action, grim reminders of how deadly that war was. So deadly, indeed, that the casualty rate for many special operations teams exceeded 100 percent – a statistical anomaly made possible when soldiers were wounded more than once in the line of duty.

For all of us, Aug. 30 will be a somber day, a good day because after 43 years, Wald, Brown & Shue will, for the first time, be together into perpetuity.

Footnote: SOG was so deeply classified that when SOG operators, including Navy SEALs, Air Force Pararescue personnel and aviators from the Air Force, Army, Navy and Marines were awarded a Presidential Unit Citation, the presentation occurred 29 years after the secret war ended in 1972.

On April 4, 2001 at a small ceremony at Ft. Bragg, N.C., a Presidential Unit Citation- the equivalent of a Distinguished Service Cross, the nation’s second highest military.

Author: John Stryker Meyer

J. Stryker Meyer served two tours of duty with Special Forces during the secret war in Southeast Asia, and has written two non-fiction books about SOG, “Across The Fence: The Secret War in Vietnam – Expanded Edition”, and “On The Ground: The Secret War in Vietnam.” Both are available as e-books through his website: sogchronicles.com

COMMENTS