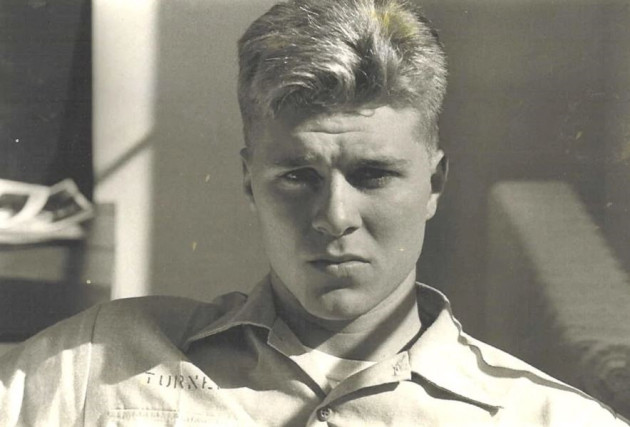

From SEAL Training to a Prison Cell: The Long Road of Dustin “Dusty” Turner

Dustin Turner did not grow up planning to die in prison.

He planned to become a Navy SEAL.

In the early 1990s, Turner was doing what thousands of young men before him had done, and thousands still do now. He chose the harder road. He raised his right hand, entered Navy SEAL training, and stepped into a world defined by exhaustion, discipline, and the quiet understanding that if you endured long enough, you might earn a place among a very small brotherhood. The best of the best.

That road did not end with graduation.

It ended with a murder conviction, a felony-murder theory, and nearly three decades behind bars for a crime even the courts would later acknowledge he did not commit. For those of you out there who did not go to law school, a “felony murder theory” is a legal doctrine that allows the state to charge someone with murder even if they did not kill anyone, as long as the death occurred during the commission of a specified felony and the accused was legally involved in that felony.

Make sense? It was about as clear as mud to me as well. It’s like being convicted of driving under the influence of alcohol when you’ve never had a drop to drink.

Below, I’ll explain to the best of my ability how this whole mess happened and why, today, Dusty Turner finds himself one decision away from either release or spending the rest of his life defined by a single night in 1995.

A Young SEAL Trainee on Leave

In June of 1995, Turner was a Navy SEAL trainee temporarily off duty in Virginia Beach. He had completed BUD/S many months earlier and was assigned to SEAL Team 4 for his final phases of training.

He and another trainee, Billy Joe Brown, went out one evening like countless young service members before them. Brown had been Turner’s swim buddy at BUD/S, and the two, by all accounts, were almost inseparable.

At Team 4, training was relentless. Pressure was constant. The night offered music, alcohol, and a brief illusion of normalcy.

At a nightclub called the Bayou, Turner met Jennifer Evans.

Witnesses later described the two talking, dancing, and lingering together as the night wore on. Evans told her friends she was staying behind and would catch up later. They agreed to return around 2:00 a.m. to pick her up.

She never made it home.

Sometime after 1:30 a.m., Evans left the club with Turner. What followed in the hours after that decision would become the axis on which Turner’s entire life would turn.

The Crime

Jennifer Evans was murdered in the early morning hours of June 18, 1995.

The act itself was close and violent. Evans was choked until she was dead. The man who applied the fatal pressure was Billy Joe Brown. Brown was seated immediately behind her in Turner’s small Geo when he choked the life out of her.

That fact matters. It has always mattered.

Turner was not the killer.

But Turner did not leave when he should have. He did not do what the law or basic decency demanded in that moment. Instead, after the murder, he stayed silent. He helped conceal what had happened. He assisted in moving and hiding Evans’ body.

Days later, the weight of that silence became unbearable. Turner led police to the remains. He told investigators what he knew.

Although it was the right thing to do, that decision, made too late, did not save him. It helped to lock his future into place.

Arrest, Interrogation, and Trial

Turner was arrested and charged with murder and abduction with intent to defile.

At his 1996 trial, prosecutors did not need to prove that Turner killed Jennifer Evans. Virginia’s felony-murder statute does not require that. It requires only that a murder occur during the commission of a qualifying felony and that the defendant participated in that felony.

The qualifying felony was abduction. Stay with me, this is a complicated case, and all is not as it seems.

At trial, the Commonwealth’s case hinged on abduction as the qualifying felony, and the felony murder charge rode on that foundation. Later, when Turner sought to undo his conviction through a writ of actual innocence, the Commonwealth leaned hard into a reframed theory, abduction by deception, arguing that deception in getting Evans to leave the nightclub could satisfy abduction and keep felony murder intact.

Once that link was established, felony murder followed automatically, regardless of who actually carried out the killing.

The Confession That Should Have Changed Everything

Years later, the foundation of the case began to crack.

In the early 2000s, Billy Joe Brown, after finding religion and the power of salvation, gave a taped confession and later signed a sworn affidavit. In both, he admitted that he alone killed Jennifer Evans. He stated clearly and repeatedly that Turner did not restrain her, did not choke her, and did not participate in the murder itself in any manner.

This was not dismissed as noise.

A Virginia circuit court later held an evidentiary hearing. Again, Brown testified under oath. The judge found him credible. The court explicitly concluded that Turner did not participate in the killing and did not restrain the victim.

Those findings should have mattered. One would think this would be enough to release Dusty Turner immediately. It was not.

The facts of the matter did not change the outcome.

When the Law Refuses to Let Go

Turner petitioned for a Writ of Actual Innocence, one of the narrowest and most restrictive forms of post-conviction relief in Virginia. The appellate court acknowledged the trial court’s credibility findings. It acknowledged that Turner was not the killer.

Then it denied relief anyway.

The reason was not factual. It was structural.

Felony murder does not ask who applied the fatal force. It asks whether a qualifying felony occurred and whether the defendant was legally connected to it. Even after the confession and the credibility findings, the Commonwealth pushed a new linchpin to keep the conviction standing: abduction by deception. The court ultimately accepted that structure as sufficient to preserve felony murder, even if Brown alone committed the killing.

That was enough to keep the murder conviction intact.

In plain terms, Turner would remain guilty of murder without committing murder.

This is how legal logic preserves itself, even when the human outcome begins to resemble something other than justice.

Accessory After the Fact in Everything but Name

There was another layer of irony buried in the record.

Accessory after the fact is a separate crime in Virginia. It is a misdemeanor. The maximum punishment is twelve months.

Turner admitted to conduct that fits that offense. He helped conceal the murder. He delayed reporting it. He eventually told the truth.

At Turner’s original trial, the jury was instructed that accessory after the fact was an option. Under Virginia law, it normally is not a lesser-included offense of murder. But once the jury was instructed that way, it became the law of the case.

By the time appellate courts addressed this issue, Turner had already served far more than the maximum sentence for that offense.

The courts noted the discrepancy.

Still, Turner remained incarcerated.

Nearly Three Decades Inside

For over thirty years, Dustin Turner has lived with the consequences of one catastrophic night.

He lost his freedom. He lost the career he was training for. He lost the chance to be known for anything other than the worst decision of his life.

Inside prison, Turner has not been violent. He has not been a threat to anyone. He has aged. He has reflected. He has accepted responsibility for what he did do and carried the heavier burden of punishment for what he did not. He has been a model prisoner.

But the system values finality. Once a conviction hardens into precedent, it becomes resistant to reconsideration. At that point, justice becomes procedural rather than moral.

His Case is Being Heard Today

On January 7, 2026, at 1:00 p.m. Eastern time, the Virginia Parole Board will hold a public meeting.

Dustin Turner’s name is on the agenda.

This meeting represents the Board’s public deliberation and vote on whether to grant parole. The Board will review Turner’s institutional record, his conduct, and the totality of a case that has followed him for decades. Victim participation is permitted. Public comment is not.

The proceedings are viewable to the public via Zoom HERE.

Virginia law requires a quorum of Board members for a parole grant, and approval requires a majority vote of those present, with additional voting requirements applying in certain life-sentence cases.

There will be no dramatic announcement and no press conference. Turner will likely learn his fate quietly, through institutional channels, as so many incarcerated people do.

For Turner, this moment is not symbolic. It is the first real opportunity in decades for the system to act on what it already knows. He was not the killer. He has already served far more time than the maximum punishment for the crime he admits committing.

Why This Case Still Matters

This is not a story about excusing bad behavior.

His failures of immediate action deserve accountability.

But that kind of accountability is not meant to be permanent.

Punishment is supposed to fit the crime. It is supposed to protect society, not satisfy institutional inertia. At some point, continued incarceration stops serving justice and starts serving habit.

The Virginia Parole Board now has the opportunity to correct that imbalance.

To recognize that a man who was not a murderer should not continue to be punished as one.

To allow a sentence to finally end, not because the law demands it, but because justice does.

COMMENTS