“You know this city’s full of hawks? That’s a fact. They hang around on the top of the big hotels. And they spot a pigeon in the park. Right down on him.” — Terry, from Elia Kazan’s “On the Waterfront.”

If you haven’t seen the movie, don’t spoil it here — watch it first, then come back.

Another great classic has found its way onto my TV, and as I watched “On the Waterfront” I was reminded once again why all of these movies made their mark. Like classic rock, they have stood out as the terrible or forgettable films of the day fell to the wayside, and these stood the test of time. I watch them as a regular audience member, not a studious purveyor of classical work, not a film critic with notes in hand, searching for faults or reasons for me to whine about modern films compared to older ones. And still, these movies are classics for a reason, and watching them reminds me of why they have survived all these years. They’re just straight up good — so before I get into my literary exploration of this film (and others to come), know that I just plain old enjoy them too.

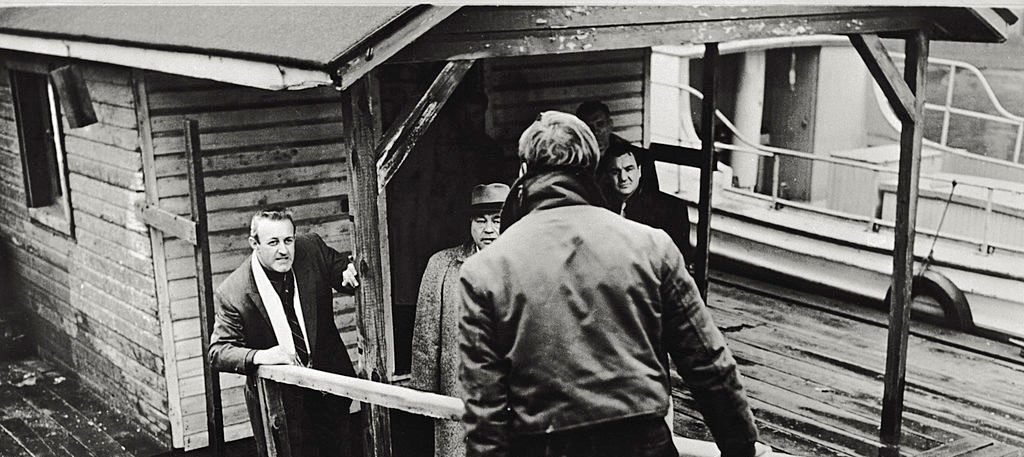

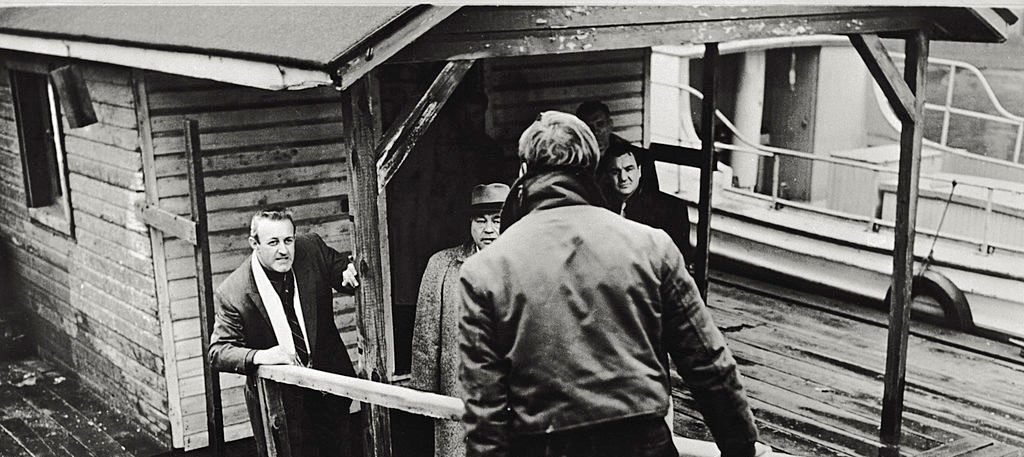

“On the Waterfront” follows Terry Mallow (played by Marlon Brando), a talented ex-prize fighter who works on the docks alongside a slew of poverty-stricken workers struggling to make ends meet. Terry is one of many thugs who work for the ruthless union boss, Johnny Friendly (played by Lee J. Cobb) They are all part of killing a would-be whistleblower who tried to speak out against the brutally enforced corruption in the upper echelons of the union. However, the sister of the murdered man catches Terry’s eye, and the two of them fall into a complicated romance that pulls him between two worlds — one of empathy and another of brutality. With the help of a local priest, some of the union members get in their heads to stand up against Friendly, and Terry doesn’t know where he ought to stand.

For the duration of the film, Terry spends much of his free time tending to pigeons on the roof of his impoverished apartment complex. He used to be a tenacious prize-fighter, deadly in the ring, but Friendly had him lose a few fights on purpose to win some bets, and that lost him his chance at the big leagues — the softer side of him finds solace in tending to the delicate birds on his rooftop. His love interest, Edie Doyle (played by Eva Marie Saint), has joined him and is watching him with longing eyes, at the rough man takes care of animals with great care and affection.

He begins to speak of hawks and pigeons, and how he has to protect the pigeons from the hawks who come from bigger, more expensive (and taller) buildings. If he doesn’t, they’ll swoop down and eat the pigeons alive.

This is quite obviously a metaphor for the powerful, predatorial union bosses taking advantage of the dock workers. The “pigeons and hawks” motif is referenced several times in the film, and the obvious question (as I outlined before) is where Terry stands. Does he stand with the pigeons, who get mauled and eaten alive but with their souls intact? Or does he stand with the hawks, who survive but at the cost of their own consciences?

Everyone is worrying about what side they are on, or which identity they belong to. Terry wrestles with this for the whole film — following his conscience only ever got him hurt, but following men like Johnny Friendly only ever hurt the ones around him. His lover wants him to stand up to them, but when that doesn’t work she wants him to run away with her. His own brother wants him to survive and look out for himself, and to work his way up the ranks of the union/gang.

In a world like that, you’re either predator or you’re prey.

Terry winds up ditching the whole metaphor entirely. After all his inner turmoil and outer conflicts, it’s as if he says, “You know? Screw all these categories and people trying to tell me what I can and can’t do. I’m not a hawk, I’m not a pigeon — I’m a man. And a man does what he’s gotta do.”

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS