The Great Chinese Famine of 1959 to 1961 stands as the deadliest man-made disaster of the twentieth century. More than a historical tragedy, it offers a grim case study in how ideology, distorted data, and authoritarian control can produce catastrophic strategic failure. For a military and national security audience, the lesson is not about agriculture. It is about what happens when a regime builds policy on obedience instead of truth.

In the late 1950s, Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward, an ambitious campaign intended to transform China from a poor agrarian society into a socialist industrial power almost overnight. Rural China was reorganized into massive “people’s communes.” Private plots were eliminated or sharply restricted, peasants were pushed into collective labor, and local officials were ordered to meet fantastical grain production targets while also diverting manpower into backyard steel furnaces and prestige construction projects.

Political enthusiasm mattered more than results. Accuracy became dangerous.

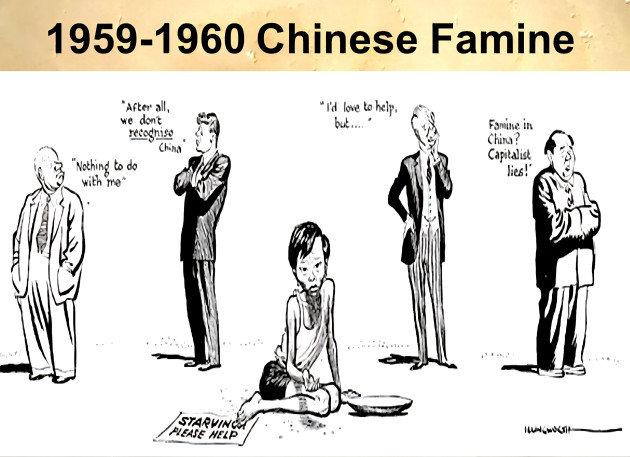

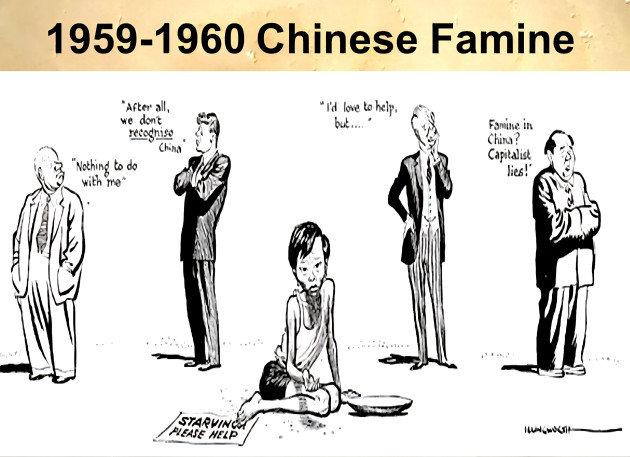

At the village and county level, the incentive structure proved lethal. Cadres inflated harvest figures to satisfy higher authorities and demonstrate loyalty to Mao. These fabricated bumper crops formed the basis for aggressive state grain procurements to feed cities and support exports. The government effectively requisitioned food that did not exist, stripping rural communities of the reserves they needed to survive. On paper, the system appeared to be succeeding. In reality, granaries were empty.

By 1959, famine spread across large areas of the countryside. Peasants exhausted household stores, consumed seed grain, foraged for roots and bark, and slaughtered livestock. Starvation and disease ravaged provinces such as Anhui, Henan, and Sichuan. Mortality surged while birth rates collapsed, a demographic signature that later revealed the true scale of the disaster.

Most modern numbers place the death toll between 30 and 45 million excess deaths, making it likely the deadliest famine in recorded history.

Information control inside the Chinese Communist Party magnified the catastrophe.

Local and provincial leaders concealed the crisis, staging Potemkin harvests and falsifying reports for visiting inspectors.

Fear and ideological loyalty suppressed honesty. At the top, Mao initially dismissed reports of famine as exaggeration or political sabotage, reinforcing failed policies instead of correcting them. The same centralized authority that allowed the Great Leap Forward to be launched rapidly also locked the system into a deadly trajectory once it began to collapse.

Only as deaths mounted and a handful of senior leaders forced a reckoning did Beijing begin to retreat. Between 1960 and 1961, grain procurements were reduced, commune controls loosened, and limited household farming was restored. China turned to grain imports, and pragmatic administrators rolled back some of Mao’s most extreme directives. By 1962, the famine had largely receded. The political system that produced it did not.

For SOFREP readers, the Great Chinese Famine is a warning from inside a closed system. Strategic warning can fail catastrophically when truth is punished. Bad metrics can drive lethal policy. A leadership cult can turn routine bureaucratic lying into mass death. It is also a reminder that states can inflict far greater harm on their own populations through internal policy than many enemies could achieve through war, while remaining largely opaque to outside observers until it is far too late.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

COMMENTS