Breakout time is not intended to suggest that Iran would necessarily decide to produce weapons-grade uranium at these inspected facilities, because the risk of detection and of potential negative international reaction is very high.

President Biden arrived in Israel, nearly 50 years after his first trip as a senator, on Wednesday to open his Middle East visit to focus on slowing down Iran's nuclear program, getting oil to American gas pumps and improving relations with Saudi Arabia. https://t.co/om6Pw4udVx pic.twitter.com/0jrnxRP93p

— The New York Times (@nytimes) July 13, 2022

How did the nuclear deal constrain Iran’s activities?

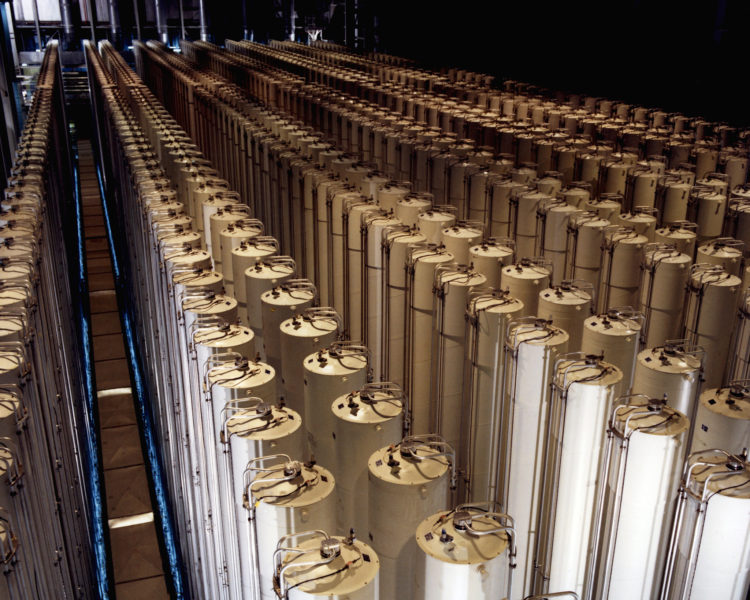

The 2015 nuclear deal put physical constraints on Iran’s enrichment program for 10 to 15 years, including the number and type of centrifuges Iran could operate, the size of its stockpile of low-enriched uranium and its maximum enrichment level.

For 15 years, no enrichment would take place at Fordow, and Iran’s stockpile of low-enriched uranium would be limited to 300 kilograms (660 pounds) at a maximum enrichment level of 3.67%. And for 10 years, its centrifuges would be limited to about 6,000 IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz.

In order to meet these physical limits, Iran shipped out to Russia most of its stockpile of low-enriched uranium and its entire stockpile of 20% enriched uranium. It also dismantled for storage inside Iran most of its IR-1 centrifuges and all of its more advanced IR-2 centrifuges. As a consequence of these limits, Iran’s “breakout time” was extended from a month or two before the deal to about one year after the deal.

After year 10 of the deal, however, Iran was allowed to start replacing its IR-1 centrifuges at Natanz with more advanced models, which it was permitted to continue to research and develop during the first decade of the deal. As these more powerful advanced centrifuges were installed, breakout time would probably have shrunk to about a few months by year 15 of the deal.

As part of the deal, Iran also agreed to enhanced international inspections and monitoring of its nuclear facilities.

What has Iran done since President Trump withdrew the U.S. from the nuclear deal in 2018?

Since the U.S. withdrew from the nuclear deal, Iran has gradually exceeded the agreement’s limits. It has increased its stockpile of 5% enriched uranium; resumed producing 20% enriched uranium; initiated production of 60% enriched uranium, resumed enrichment at Fordow; and manufactured and installed advanced centrifuges at both Natanz and Fordow.

Iran has also begun to restrict international monitoring of its nuclear facilities. In June 2022, for example, Iran announced that it was disconnecting cameras installed under the 2015 nuclear deal to monitor its nuclear facilities.

As of May 2022, the International Atomic Energy Agency estimated that Iran had about 1,000 kilograms (2,200 pounds) of 5% enriched uranium, about 240 kilograms (530 pounds) of 20% enriched uranium and 40 kilograms (88 pounds) of 60% enriched uranium.

As a result of this growing stockpile of enriched uranium and the use of advanced centrifuges, Iran’s estimated breakout time has been reduced to a few weeks. So far, however, Iran has not decided to begin production of weapons-grade (90%) enriched uranium, even though it is technically capable of doing so.

Most likely, Iran is behaving cautiously because its leaders are concerned that producing weapons-grade uranium would trigger a strong international reaction, which could range from additional sanctions to military attack.

***

This piece is written by Gary Samore, Professor of the Practice of Politics and Crown Family Director of the Crown Center for Middle East Studies from the Brandeis University. Want to feature your story? Reach out to us at [email protected].

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

COMMENTS