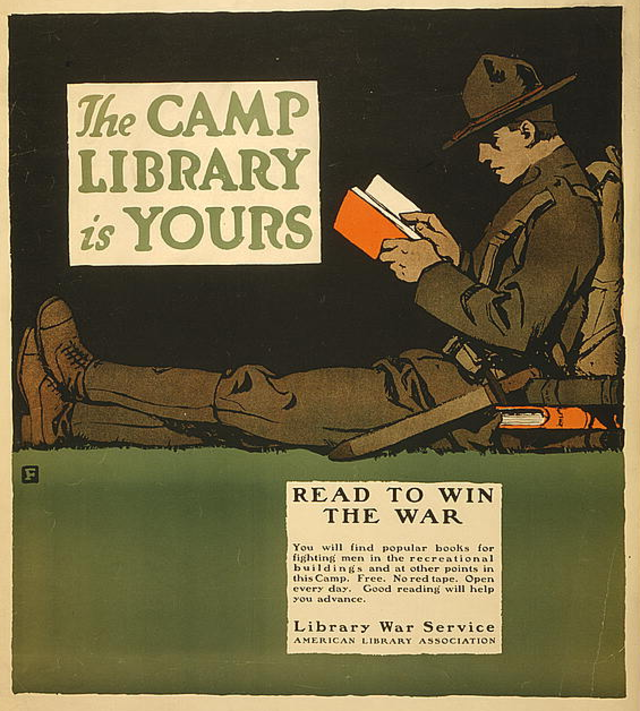

These categories are typical of reading lists from the past ten years. While the U.S. Army Center of Military History archive dates to 2011, the tradition of the reading list is not new. A 1954 military review from the Command and General Staff College (CGSC) mentions a suggested reading list for officers that “has been used in the Army for a number of years”. The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) professional reading program unofficially began 200 years ago when “the Navy ordered its ships be outfitted with a reading list of 37 books in order to help train and educate Sailors.”

What are you reading?

The reading lists published by chiefs of staff, commandants, and others often come with descriptions citing critical thinking, applying history to the present, or keeping up with an increasingly complex world. Ask junior officers about the culture of reading in the military, and they’ll say that they’re always prepared to answer the question “What are you reading?” A 2010 edition of the Military Law Review shares a story about students at the CGSC meeting the new commandant during PT. As they stretched, the commandant asked the students one by one to share reading recommendations. While some students faltered, the Review author had an answer: “April 1865: The Month That Saved America” (this fits nicely into Most Likely to Turn into a Mel Gibson Movie).

Answering the question “What are you reading?” may sound like the military version of “salon culture,” a way to posture intellect in polite society. In some ways, this is true. The culture of reading is rooted in the two main career tracks, enlisted and officer. Like their predecessors in the European military tradition, commissioned officers often had a classical education, which included learning the languages and “great books” of antiquity. The remnants of a classical education are still present. “The Aeneid,” Virgil’s epic poem about the Trojan War, frequently appears on military professional reading lists. While the enlisted track has reading lists, they tend to be those written by enlisted service members, for enlisted service members. They’re the Mel Gibson-type books that contain profiles of NCOs and popular press historical accounts.

While it’s true that a reading culture was always important among society’s elite (the group that historically fed the officer class), professional reading lists go beyond mere tradition. These lists are a means of public relations for an institution faced with tough ethical decisions and a recruitment crisis.

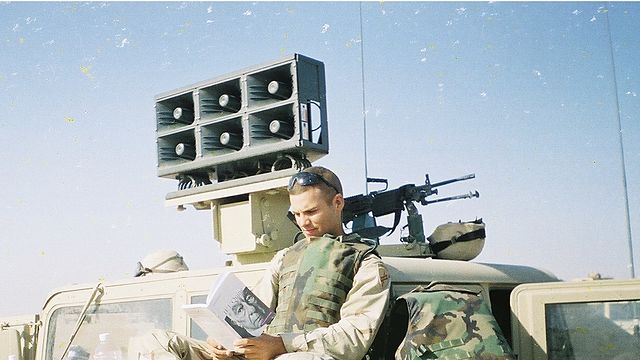

Reading lists are certainly more public than they used to be and have even become newsworthy. Gen. McConville tweets his monthly selection, and CNO Admiral Michael Gilday received backlash from the House Armed Services Committee after asking sailors to read Ibram X Kendi’s “How To Be An Antiracist”. Despite the recent controversy, the fact that officers are always reading–and everyone knows it–helps provide a veneer of romanticism that the military has enjoyed for centuries, even millennia. Both the despotic (Napoleon, Caesar) and the more “buttoned-up” (McChrystal, McRaven) have used their genteel public image to justify military action from sieges to drone strikes. The memoirs and other hero stories perpetuate “warrior worship” in which people otherwise critical of military action demonstrate unwavering support for individual service members. When an individual is gallant and educated, a morally questionable action can become brave and self-sacrificing.

A literary public image makes it easier to obscure costs in human lives

The military’s reading culture also helps campaigns appear backed by theory, as though decisions are directly related to the volumes of history, philosophy, and tactics read by officers. In this way, the military finds a commonality with other leaders. I often forget, for instance, that President Obama, arguably one of the more literary presidents of my lifetime, backed the Afghanistan surge and approved more drone strikes than any previous administration. A literary public image makes it easier to obscure costs in human lives than when those same decisions are made by, say, a president whose popularity hinges on not being one of the elite. The presence of the American literati in an administration, whether they be presidents or secretaries of defense, can lead to two assumptions: civilians would make the same decisions if they were as well read, and decisions are judged by the articulation of the person who made them.

Public relations aside, reading lists capture the evolving culture of the military. What the most recent lists say about military culture is twofold. First, some books capture the infiltration (or at least the fear of infiltration) of “Wokeness,” a movement concerned with politically-correct speech and structural “-isms” (racism, sexism, ableism, etc.). In addition to the Navy’s inclusion of “How To Be An Antiracist”, other reading lists reflect a possible shift towards Wokeness. The Chief of Staff of the Air Force, for example, includes Caroline Criado Perez’s “Invisible Women: Data Bias in a World Designed for Men,” an argument that men are the baseline for the data behind public policy decisions impacting everything from education to healthcare. This is perhaps the reading list equivalent of the Air Force’s maternity uniform or the Army’s hairstyle guidelines, two recent choices that received as much backlash as the Kendi book.

Books About Running A Bureaucracy Instead of Winning Battles

Second, the reading lists reflect that the peacetime military, in the opinion of some service members I’ve spoken with, looks more and more like a bureaucracy that exists primarily to employ people. Mike Hennelly, an Army Ranger and West Point instructor, called the 2017 Army reading list “breathtakingly mediocre,” lamenting that nearly a quarter of the books are international relations books not applicable to the military. Many of the books in the category I call TEDxMilitary are the kinds of leadership books I read in my college management classes. Gen. McChrystal, in fact, founded a management consulting firm in 2011, and he’s not the only leader who transitioned seamlessly to advising Fortune 500 companies. General James Mattis, Admiral McRaven, and others have post-military careers that include consulting and serving on boards of directors. Even junior officers in combat branches have privately shared with me their concerns that their day-to-day tasks are exclusively managerial and administrative ones. They have shifted from preparing for deployment to creating PowerPoints, inventorying equipment, and other paperwork. The reading lists demonstrate a de-emphasis on tactics in favor of organizational management, a skill that has become more important as the average officer’s day is filled with the bureaucratic grind of meetings and emails.

The reading lists ultimately symbolize the military’s main challenge. American society seems to demand two paradoxical things: the military must maintain the traditions that made it successful while keeping up with changing social norms. Reading lists show the military at a crossroads, an attempt to celebrate the past but also recognize that war–and the people who engage in it–don’t look like they used to. The public image that reading lists create promises recruits both a “Band of Brothers”-esque experience and an intervention from a, shall we say, militant human resources department should anything go wrong.

As the U.S. contends with Russian and Chinese hegemony and the crisis in Ukraine, I can imagine that military reading lists will become dominated by portraits of Cold War heroes or even tactical books recommending our expansion in the Arctic. Amidst the “culture wars,” the ongoing tension between free speech and feelings, I can imagine more books about structural “-isms” or forgotten contributions to history. When I see these headlines and want a better sense of what military leaders are thinking, I’ll first turn to service members and ask, “What are you reading?”

COMMENTS