In the annals of Naval Aviation for the U.S. Navy, one of the pioneers for combat tactics was John “Jimmy” Thach who, during World War II not only came up with one successful tactic but two. He was credited with the “Thatch Weave” where U.S. fighters could successfully counter the better maneuverability and climbing ability of the Japanese. And later he perfected the “Big Blue Blanket” which defended the skies above the U.S. fleet from Japanese kamikaze attacks.

Thach would serve for forty years in the Navy and retired as an Admiral with a four-star billet as the Commander in Chief of Naval Forces Europe in 1967. He died on this day in 1981.

Thach was born in Pine Bluff, Arkansas in 1905. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1927. His first two years as an Ensign was aboard battleships. But Thach transitioned to Naval Aviation in 1930. He served as a test pilot and aviation instructor, having a reputation as an expert in aerial gunnery. He remained in those billets for the next ten years.

World War II Fame:

In the early days of WWII, the U.S. fighters were easily outclassed by the superior Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighter, which was the Imperial Navy’s standard fighter aircraft.

Thach who in command of Fighting Squadron Three (VF-3) aboard the U.S.S. Lexington knew the Americans had to overcome the superior performance of the Zero and had begun working on tactics to combat this disadvantage even before the United States entered the war.

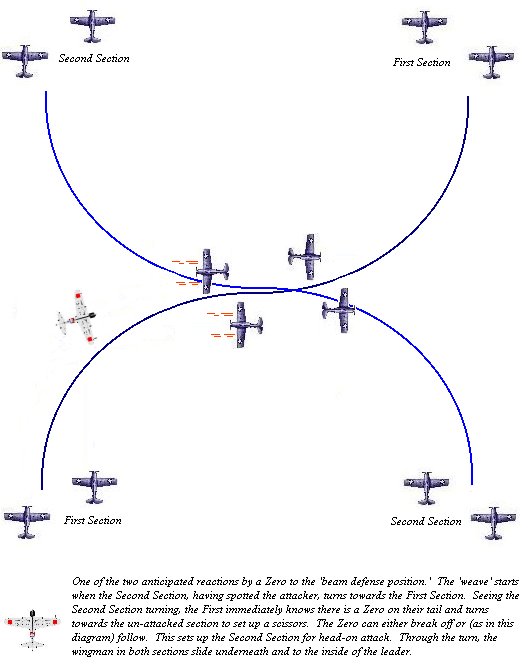

He came up with a tactic that he called the “ Beam Defense Position” but one of his aviators called it the “Thach Weave” and the name stuck. Thach eschewed the normal three plane formation that the U.S. had been using and went to pairs of Wildcat fighters working in unison.

From Wiki: It was executed either by two fighter aircraft side-by-side or (as illustrated) by two pairs of fighters flying together. When an enemy aircraft chose one fighter as his target (the “bait” fighter; his wingman being the “hook”), the two wingmen turned in towards each other. After crossing paths, and once their separation was great enough, they would then repeat the exercise, again turning in towards each other, bringing the enemy plane into the hook’s sights. A correctly-executed Thach Weave (assuming the bait was taken and followed) left little chance of escape to even the most maneuverable opponent.

This maneuver allowed American pilots to fight the more agile Japanese fighters on much more equal terms, as they’d continue turning as a tandem with the enemy as if he tried to get on the tail of an F4F Wildcat fighter, he’d leave himself open for deflection shots, something American pilots became quite adept at.

Success at Midway and Beyond:

Thach first attempted his new tactic while commanding VF-3 while flying off the Yorktown during the Battle of Midway in the early morning of June 4, 1942. He was leading a six-plane sortie of Wildcats from his squadron, escorting twelve Douglas TBD Devastators, the outdated and slow torpedo bombers of VT-3 led by Lieutenant Commander Lance Massey from Yorktown. This would be the last engagement that the Devastators would fly in, as they’d soon be replaced by Grumman TBF-1 Avengers.

The flight of aircraft discovered the main Japanese carrier fleet and were immediately set upon by 15 to 20 Japanese Zero fighters. Thach immediately pressed home his new tactic. His wingman Ensign R. A. M. Dibb was quickly set on by Japanese Zeros. Dibb, performing the weave perfectly, turned toward Thach’s aircraft, who dove under his wingman and fired at the Japanese plane’s belly, igniting the engine.

Although the American Wildcats were outnumbered and easily outmaneuvered, Thach quickly shot down three Zeros and while his wingman Ensign Dibb accounted for another, at the cost of just one Wildcat.

When the Japanese lost four of the top-of-the-line carriers at Midway, the cream of the Japanese naval aviators were also mostly gone with them. And thru attrition, their best aviators would soon be gone. The Americans had a better way. They pulled some of their best aviators out of the line to train the next group of aviators, giving them the benefit of their experience. With the updated American fighters soon coming, the Hellcat and Corsair for the naval aviators, the United States would soon wrest control of the skies over the Pacific.

Thach began to train other U.S. aviators in the best ways to combat the Japanese pilots, including the Thach Weave. When the Marines were fighting over Guadalcanal their pilots flying out of Henderson Field began to use Thach’s tactic. And it not only confused the enemy but infuriated them as well. One Japanese ace, Sub-Lieutenant Saburō Sakai flying out of Rabaul wrote this about the tactic.

For the first time Lt. Commander Tadashi Nakajima encountered what was to become a famous double-team maneuver on the part of the enemy. Two Wildcats jumped on the commander’s plane. He had no trouble in getting on the tail of an enemy fighter, but never had a chance to fire before the Grumman’s team-mate roared at him from the side. Nakajima was raging when he got back to Rabaul; he had been forced to dive and run for safety.

Thach would later create the “Big Blue Blanket” over the fleet to protect the aircraft carriers from Japanese kamikaze attacks. His plan was to have a constant presence of the blue-painted Hellcats and Corsairs over the fleet at all hours. He recommended larger combat air patrols (CAP) stationed farther away from the carriers, and a line of picket destroyers and destroyer escorts placed 50 or more miles from the main body of the fleet to provide earlier radar interception and improved coordination between the fighter director officers on board the carriers. Thach also called for the dawn to dusk fighter sweeps over Japanese airfields.

Thach would be credited with shooting down six aircraft during the war, making him an ace. He’d be promoted to Commander and later became the operations officer to Vice Admiral John S. McCain Sr., commander of the Fast Carrier Task Force. Thach was aboard the battleship Missouri for the Japanese surrender in Tokyo Bay in September 1945.

Korean War and Beyond:

During the Korean War, Thach would command two different aircraft carriers, the Sicily CVE-18 and later the Franklin D. Roosevelt CVA-42. After being promoted to Rear Admiral, Thach would play a key role in the U.S. anti-submarine warfare development.

His antisubmarine development unit, “Task Group Alpha”, with the aircraft carrier Valley Forge CVS-45 as his flagship became the cutting edge of this new type of warfare which was a primary focus at the time in the ongoing Cold War. An annual award was later established in his name for presentation to the top ASW squadron in the Navy.

Later at the Pentagon, he presided over the development of the A-7 Corsair before retiring from the Navy in 1967 with four stars and 40 years of service.

He passed away on April 15, 1981, just four days shy of his 76th birthday. Thach is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

He was awarded the Navy Cross, the Navy Distinguished Service Medal, the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit with “V” device, the Bronze Star with “V” device and the Navy Commendation Medal with “V” device.

Photos: US Navy, Aviation History

COMMENTS