Wake Island is made up of three islands in the atoll, for a total of 3 square miles. It sits a couple of thousand miles West of Hawaii, but only six hundred miles from the nearest Japanese bases in the Marshall Islands group, equal to the distance from Boise to Seattle.

I had been to Wake Island as a 19-year-old Marine PFC on my way to RVN. As the aircraft refueled, I watched the sun come up from the vantage point of the Marine memorial.

My MOS was 0311 (rifleman). As an infantryman, my view of the defensive qualities of Wake Island was about the same as the top of a pool table. Picture an airstrip in the Nevada desert, no palm trees, just miserable ironwood scrub growth, some man-high, surrounded not by desert but by ocean. Its greatest height above sea level is 20 feet, but most of the island is closer to 15 feet.

Wake had no fresh water, no anchorage, just birds, rats and crabs. A very unloved bit of coral in a very large ocean. Formal possession by the United States taken (almost as an afterthought) by troops on their way to the Philippines during the Spanish-American War.

In 1934, FDR got the attention of the Japanese when he declared Wake a federal bird sanctuary, under the protection of the United States Navy. And so, for a time it sat.

In 1935, Pan Am (with much government help) set up a base for their giant four engine seaplanes, the “China Clippers.” Wake became a stop on the way to the Philippines and China.

In 1939, Congress voted its approval for a naval base at Wake Island, then failed to fund it until a year later, a delay that would prove extremely costly.

By late 1940, the first civilian contractors (under Morrison Knudsen out of Boise) started work on the island. It had been left desperately late, but it was still possible to build a viable defense. But political and military brass would see to it that it did not happen. Priority was given to bases in the Caribbean that the Germans couldn’t possibly menace without taking Britain first. Many other decisions, and lack of decisions, would doom the outpost.

The number of workers, and later, the number of Marines and other military people, would be determined by the facilities to support them. Water was the biggest problem, but shipping and the ability to handle it (minus any anchorage) was also a factor.

At one point before the major construction started, the M-K workers were idle for a period. It was the perfect time to build an airfield. But the Navy brass refused to issue an authorization – they wanted to quibble about minor details. By the time that they approved building the airfield, all 1200 workers were fully occupied and had to be pulled from other urgent projects.

The pay for the workers was good, but it involved a 9-month contract in a locale with no alcohol, no women, and mandatory overtime. It also involved being at the sharp end of any trouble with the Japanese.

Some workers began to feel exposed, but the Navy told them that “…within 36 hours of any attack, fleet units would arrive at Wake…” This was untrue even before the Pearl Harbor attack. Many of the workers had their first good employment coming out of the Depression, and quitting their contract early (at that time) would disqualify them for further government work back in the States.

In August of 1941, Admiral Bloch, in Pearl Harbor, came to the conclusion that any defense of Wake prior to the completion of all facilities and defenses would require the assistance of the contract workers in both support and combat roles. It was decided to play down their vulnerability to prevent many from quitting.

Also in August, the first elements of a Marine Defense Battalion were shipped to Wake with less than 1/3rd of their strength and short 75 rifles. Six five inch guns, minus some sighting equipment. A number of .50 and .30 caliber machine guns. Twelve 3-inch (76mm) anti-aircraft guns (with only a single working anti-aircraft director among them), and not enough men to man them. It just kept piling up.

The Marines would eventually wind up at about 50% of their strength. A call went up for civilian workers to be trained, both for moving the big guns around and serving on crews for the 5-inchers and the machine guns. Two hundred civilian workers stepped forward.

A line was being crossed and the high brass tried to play it both ways. The Marine battalion commander and the Navy base commander (who showed up shortly before the war started) were not given any authority to actually *enlist* any of the workers, even as reservists.

It was said that the Japanese would execute any civilians fighting with the military, yet that is exactly what the brass was counting on, that the civilians would fight. This was not rocket science. Enlist those that you wanted, who volunteered, in the Reserve. Give them armbands and they would fully qualify under the Laws of Land Warfare as legal combatants. Failure to do this had long-lasting repercussions.

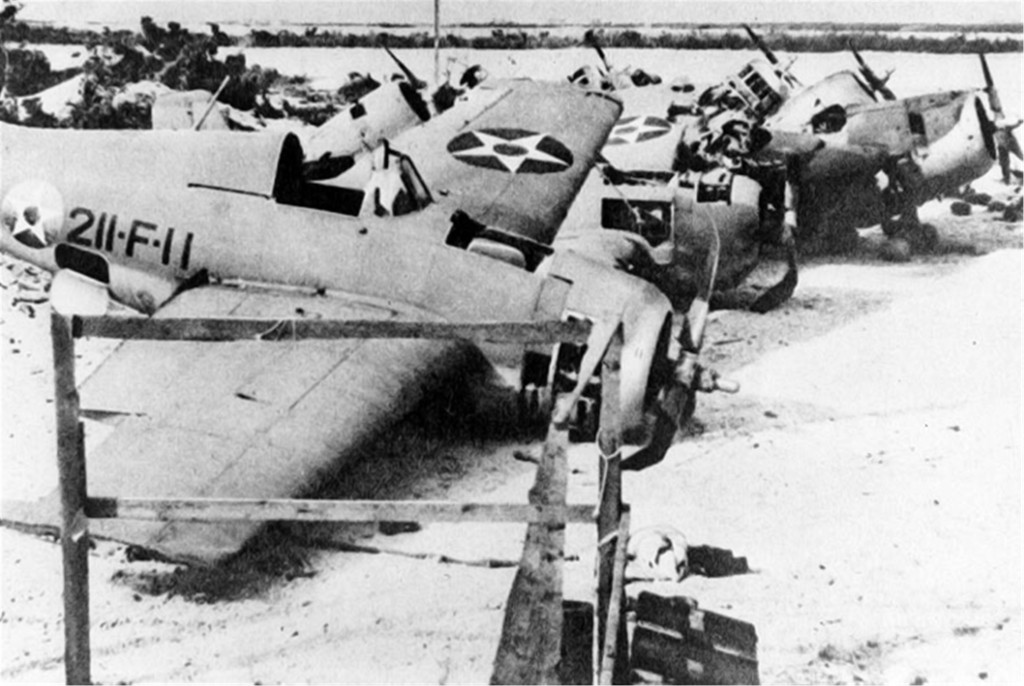

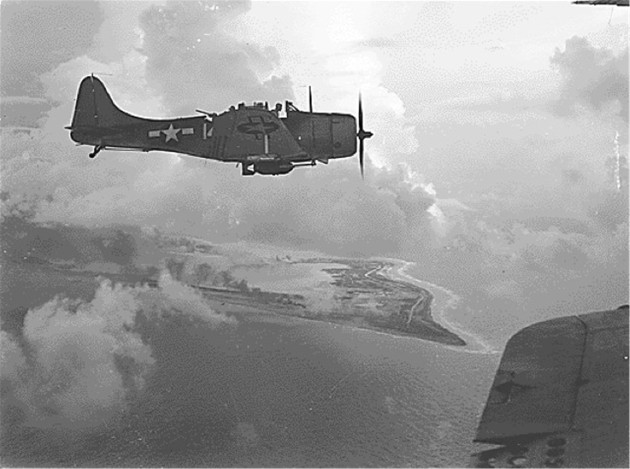

The high brass wasn’t done messing with Wake yet. A dozen Marine Wildcats were flown off a carrier to Wake on December 4th, 1941. Only one had self-sealing fuel tanks. No armor on any of the aircraft, no radio homing devices, and the bombs stored on Wake did not fit their bomb racks. Only three of the aviators had previously flown Wildcats… for no more than 30 hours.

Wake Island had several radars. They gathered dust for months at a dock in Pearl Harbor. In the end, they were never delivered. A couple of Marines on a water tower with field glasses might, at best, give 30 seconds warning. Sound detection did no good because Wake’s surf constantly pounded the shore. Eight of Wake’s aircraft would be destroyed on the ground in the first attack.

Right up until some hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the high brass gave defense construction a low priority,using the civilian contractors on less important projects. The Marines were forced to spend much of their time in time-consuming semi-manual refueling of B-17s heading to the Philippines, in time to be destroyed on the ground there.

It is not my intention to cover the fight for Wake Island here. Suggested books and videos appear at the end of this article.

When the fight for Wake took place, roughly half of the civilian workers either helped move guns between air raids so the Japanese wouldn’t locate them, or actually manned some guns and later fought against Japanese landing forces. The first Japanese Naval attack on Wake should have succeeded, simply lay off out of range and hammer it into dust, but the Marines played possum and the Japanese got closer and closer until they were handed their heads.

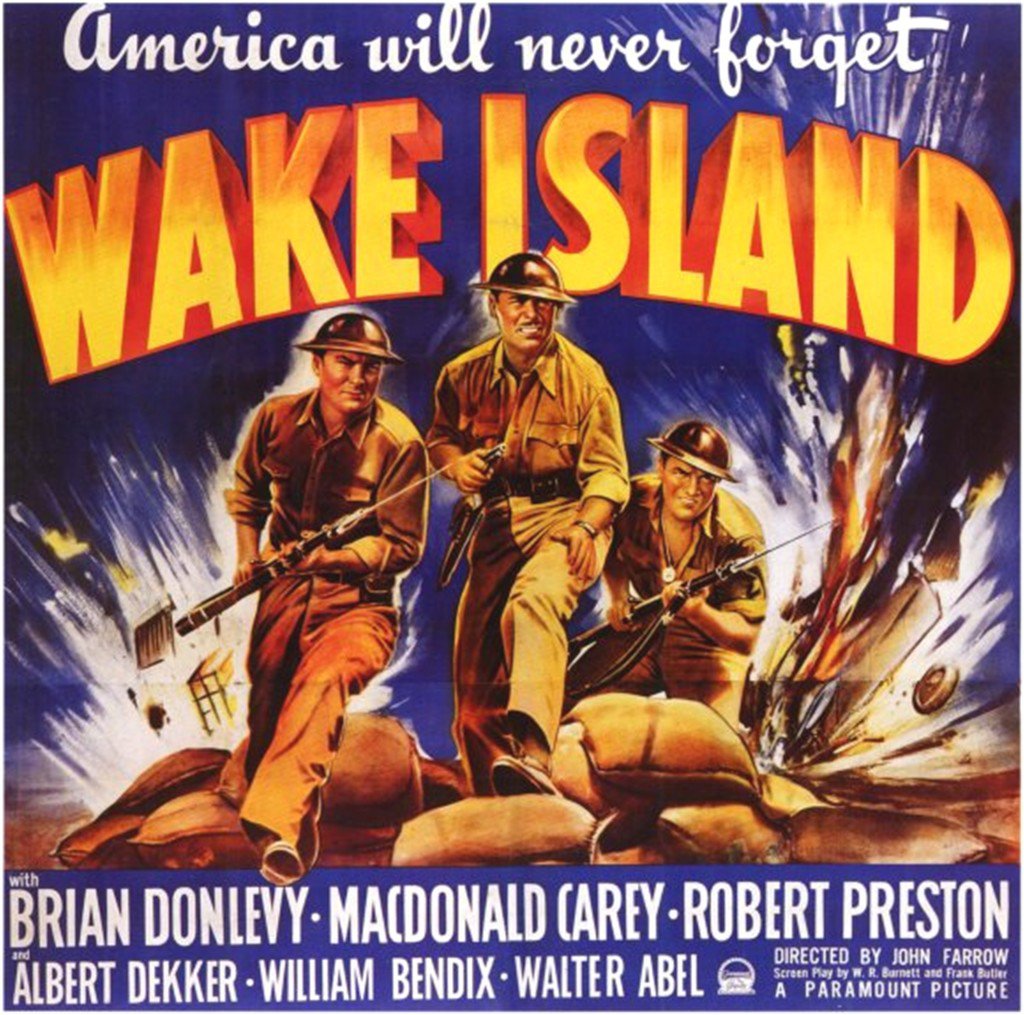

Back in the U.S., this was the only real positive news that the folks had since Pearl Harbor, and the administration played it up. Simple code padding “Send us… message… more Japs…” released to the press by the administration as Marines saying, “Send us more Japs…” Hollywood started putting a film together.

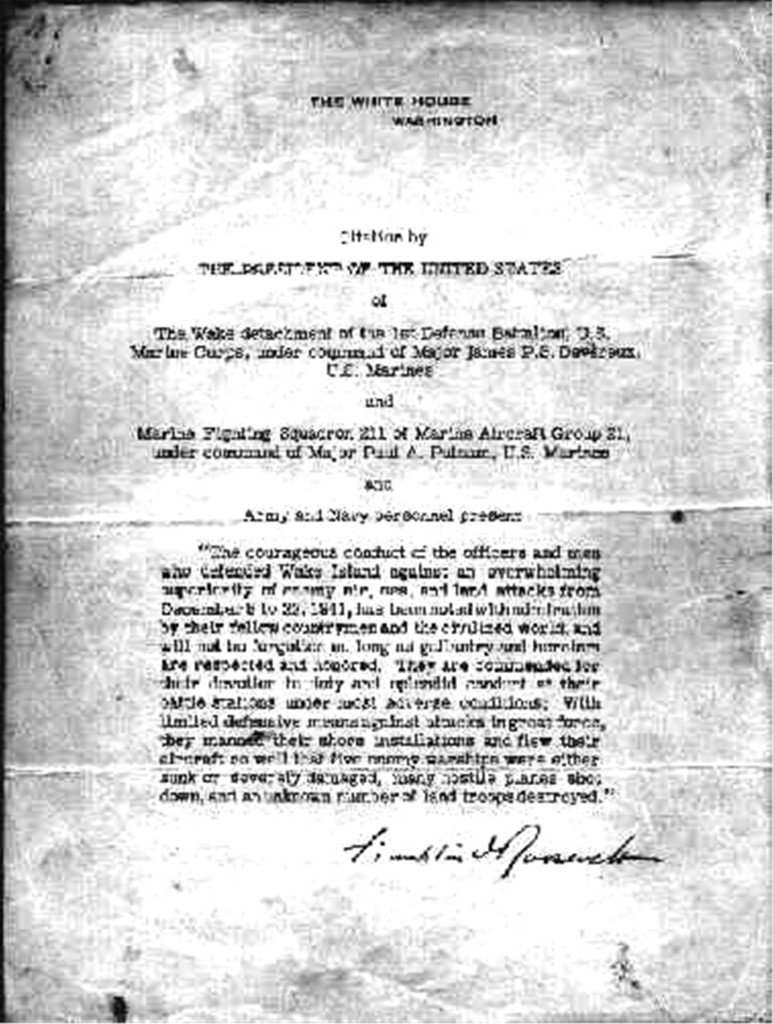

Admiral Kimmel, head of Pacific Fleet hadn’t wanted the Fleet at Pearl Harbor, but he would be held responsible. He ordered a relief force to Wake: carrier, destroyers, Marines and a lot of ammo on a transport (see photo). His orders were of the “…with your shield or on it…” variety.

Wake had a chance.

But Kimmel was relieved, and the incoming CINCPAC had to leave the running of the relief force to the Admiral on the spot, who wasted time refueling and when almost within air support range talked himself into abandoning Wake. Wake was simply advised by radio that any ships that they might see would not be American.

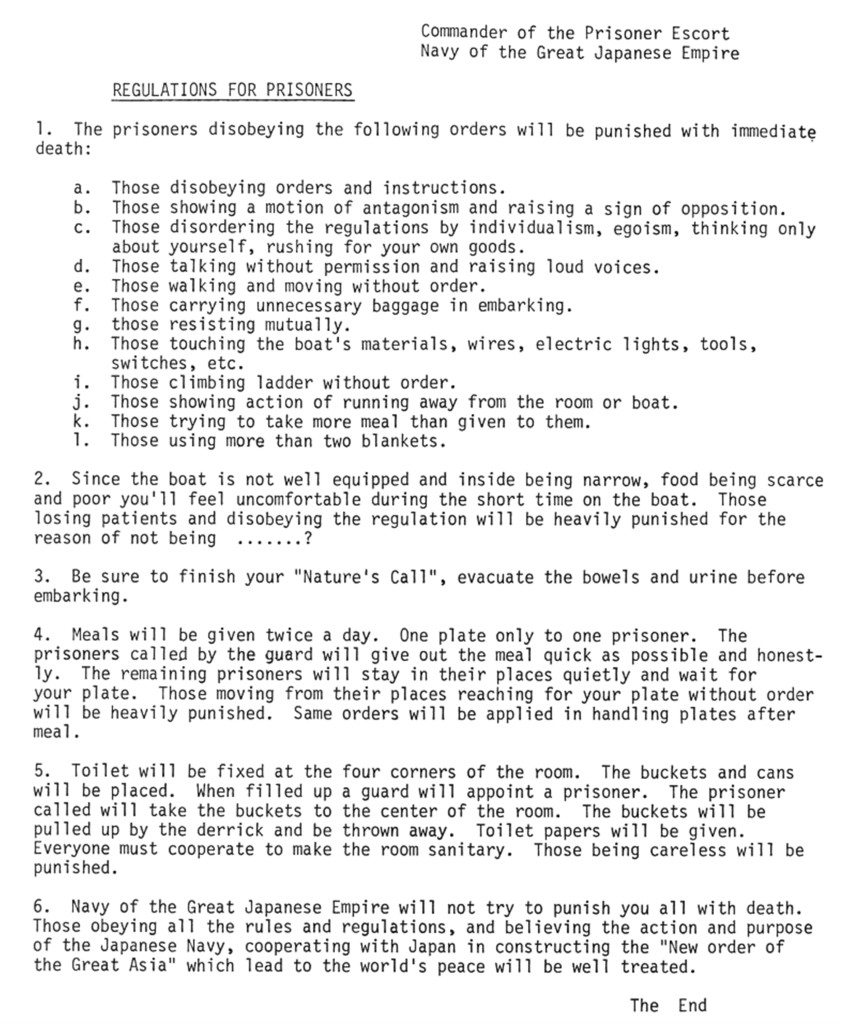

So Wake fell and the first of the prison ships left. Other prisoners would later be sent off the island as slave labor in Asia. One hundred civilians were kept on the island.

Hollywood released the film “WAKE ISLAND” that was at least rousing, if not accurate. At the end, the implication was that all Americans on Wake had been killed. Worse, a subplot implied that prior to the first attack, the civilian workers were a massive problem for the military, which was completely wrong. Both errors would haunt the Wake survivors.

The Japanese simply decided to classify all Americans removed from the island as prisoners of war. The American government had other ideas.

So far as the United States Government was concerned, the 1200 civilian workers were *not* prisoners of war, they were simply unemployed workers. Morrison Knudsen paid the families an extra month salary out of the goodness of its heart, but the government was not interested.

Eventually, months later, a small Social Security stipend was given to families of workers held by the Japanese. In the last year of the war a larger, more realistic amount was voted, but it was not retroactive.

One of the workers had been on Wake with his father; both survived the war. At the Wake reunion in 2013, he read a poem that he had written. He explained that, while a few elderly Japanese civilians risked their lives to get some food to him and his father, his mother had been evicted from her home by the bank for insufficient payment. She died before he and his father got home.

In 1942, American officers who had been in the Bataan Death March and the camps escaped. Upon their return to the U.S., they were told that they would be reduced to the ranks and imprisoned if they told the American people what had happened, and what was happening to their men.

The “official” reason was that “The Japanese might treat our men even worse.” (This same cowardly reasoning would be used in government briefings to the families of American POWs in Vietnam.) The real reason was that the administration was having a hard enough time selling the “Europe First” decision. In 1944, the story looked to break so the government broke it first. The Wake prisoners would also suffer from this government cover-up.

The war came to an end. Of the total numbers on Wake, some had died in the fighting, some died in transport, or were worked to death or killed by guards or vanished. Eleven died on an unmarked Japanese ship that was torpedoed.

After the Japanese surrendered on September 4th, 1945, the last Marine officer transferred off Wake before the war took the surrender of the Japanese survivors on Wake (many had died of starvation). The senior officers were fat enough. No Americans on the island.

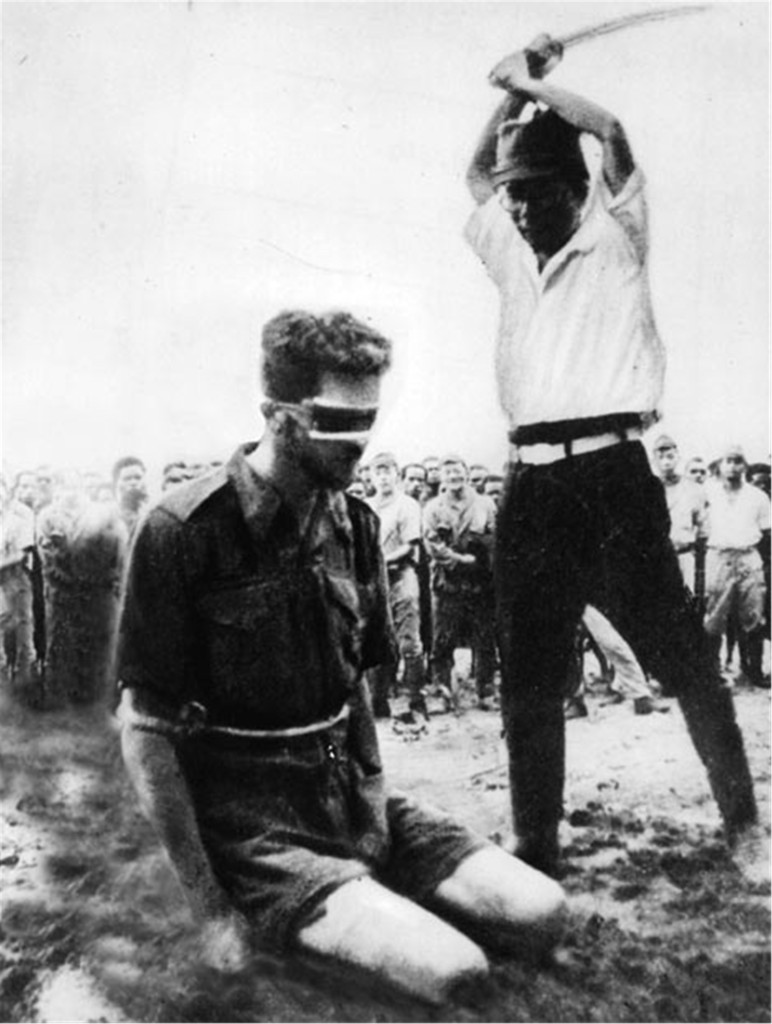

The Japanese claimed that the remaining 98 killed (after two other deaths) half in an air raid… and half during an “insurrection…” An investigation showed that, on the same date that I am typing this, 70 years ago today after an air raid, the Japanese took all the prisoners to one end of the island and shot them all down. The two top Japanese officers were tried and hanged.

Meanwhile, the health of the workers and Marines had been largely destroyed by the Japanese. The workers were not eligible for veterans benefits, and the military, well, in many cases the VA wanted “detailed medical records” relating to their deteriorating condition in the Japanese slave camps. The only records might be a list of the number of slaves who were dead at morning roll call.

The VA in many cases tried to list as many as possible at 10% disability and get rid of them. It took a long time, often years, to correct this injustice.

Justice itself was hard to come by. After the war, the 8th Army was clumsy in its investigation of Saito. He vanished, an amazing trick in a country where the police know what your parakeet had for breakfast. His wife was found with much loot taken from the prison ship.

All but one of the executioners on the ship (good case that he had been forced) were convicted and given life sentences at hard labor. Within 13 years, the Americans, “to appear open-minded” to the Japanese, had all of them freed.

The former prisoners could not sue the Japanese government. The U.S. government forbade it, stating that all such claims died with the peace treaty with Japan in the early 1950s. There are less than 40 Wake survivors alive today. They have a suit against major Japanese firms that exploited their slave labor, but the U.S. government is not behind the effort. It will doubtless die in a few years with the last of them.

The U.S. government ultimately decided to “compensate” the former prisoners with the princely sum of $2.00 per day, which would not even cover the medical bills of the civilians.

In 1981, after so many survivors had died and so many had suffered, the U.S. Government at last decreed full veterans benefits to the surviving Wake Island civilian workers, to include campaign medals, exactly as if they had been enlisted.

To say that the remaining survivors are bitter would be an understatement. Yet, to a man, they love their country. They hold it in a great deal more esteem than its government held them for so many years.

So I finished the story of the incident on the Nitta Maru. I introduced my landlord of 12 years, whose father was an M-K survivor of Wake (died 1969), and I recalled my sunrise on Wake 44 years ago.

But of the 70 souls at the reunion, only 5 were Wake survivors. The other 35 were mostly unable to travel. They are all in their 90s, after all. The balance at the banquet, children, grandchildren and so on of survivors, and of those who did not survive, and me a stand-in for someone who wanted to honor their uncle.

Alice Ingham is the widow of a survivor of Wake. She is the driving force behind the reunions, but it gets harder. The organization itself actually disbanded in 2004, but too many did not want to let go. Maybe one more reunion… Maybe.

The part of our population that knows of Wake Island has heard of the gallant defense. Few indeed have heard of the unjust price that so many paid both for reckless unpreparedness, and for what happened after the Colors were lowered.

Further Information

- Pacific Alamo: The Battle for Wake Island

- BUILDING FOR WAR: The Epic Saga of the Civilian Contractors and Marines of Wake Island in World War II

- WWII Battle of Wake Island Alamo of the Pacific (Video)

* We referred to this image as the execution of “an allied soldier.” However, this is Sergeant Leonard George (Len) Siffleet, of the Australian Army. Thanks to SOFREP reader Roger, from Melbourne, Australia for providing information about Len to us. Please remember Sergeant Len Siffleet in your thoughts.

COMMENTS