With all eyes seemingly focused on the insurgent offensive in Iraq and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS), another theater of the international war on terror has produced some encouraging signs for progress against fundamentalist militants. In Pakistan, the national government has signaled what has been interpreted by many to be a fundamental change in the government’s position on negotiations with Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and, relatedly, a reconceptualization of Islamabad’s relationship with The Haqqani Network.

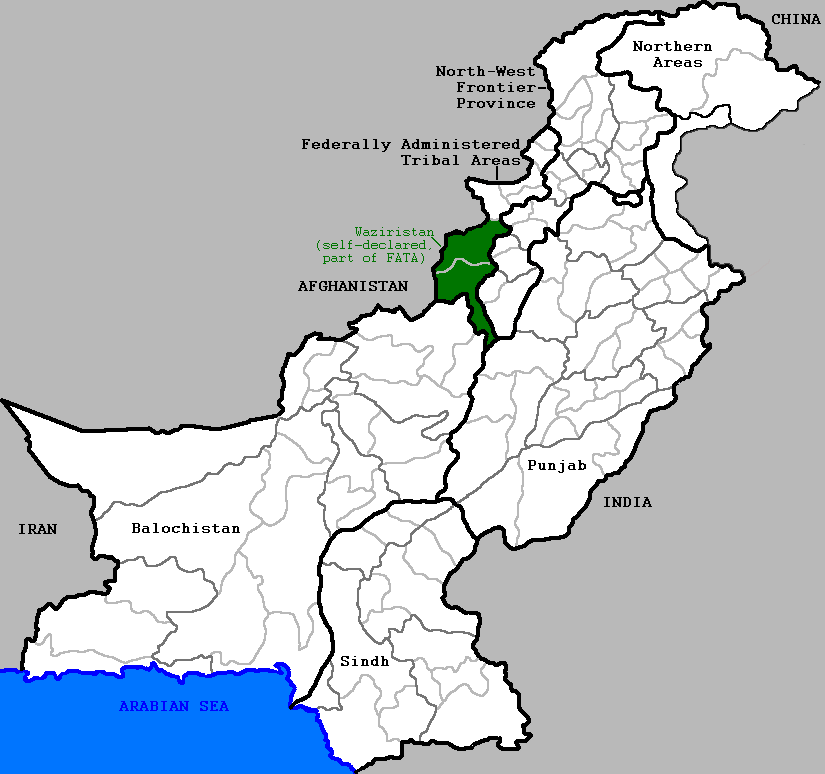

On June 15, the Pakistani military launched a massive offensive from the ground and in the air. Named “Zarb-e-Azb” (“Sharp and Cutting”), the operation is targeting insurgent havens and camps throughout the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA). Supported by impressive and decimating air power, ground forces moved into North Waziristan, conducting sweeping operations that have left multitudes of insurgents dead and wounded.

The mission has found wide-ranging public support, burgeoned by domestic dissatisfaction with insurgent attacks targeting citizens, government officials, and military service personnel. The operation is larhely aimed at disrupting and destroying elements of TTP, the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), and the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU).

The aforementioned public support is largely derived from a backlash following the attack on the airport in Karachi on June 8. Militants, disguised as airport employees, conducted a complex effort inside the airport, gaining access to secure areas and exacting a bloody toll on workers and civilians. During the six hour battle, dozens were killed and more were wounded:

The Pakistani Taliban have said they were behind an assault on the country’s largest airport that killed at least 28 people, including all 10 attackers. The raid on Jinnah international airport in Karachi began late on Sunday at a terminal used for VIPs and cargo. Security forces battled the militants for at least six hours, finally gaining control around dawn. The airport has now reopened and flights have resumed.

Karachi has been a target for many attacks by the Taliban. A spokesman for the group, Shahidullah Shahid, said the aim of Monday’s assault had been to hijack aircraft, and was “a message to the Pakistan government that we are still alive to react over the killings of innocent people in bomb attacks on their villages”. (BBC, June 9)

The IMU claimed credit for the attack in Karachi and has been a main target of the subsequent Pakistani military effort to dislodge and destroy militants in the FATA. Follow-on attacks in the wake of the larger effort on June 8 were reported on June 10 with militants targeting Pakistani security positions outside the airport:

Just two days after Pakistanis were jolted by a deadly terrorist attack on the country’s busiest airport, militants again opened fire on security forces at Karachi’s international airport Tuesday. Pakistani police and soldiers quickly repelled the assault, and there were no reported injuries. But the incident forced the closure of Jinnah International Airport for the second time in two days and highlighted the threat posed by the Pakistani Taliban.

The clash appeared to push the country closer to a major conflict with the radical Islamist group. On Tuesday morning, the Pakistani military announced that it had carried out airstrikes against Taliban strongholds in northwestern Pakistan. An army official said 25 militants were killed. Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar Ali Khan warned that the airstrikes could lead to retaliation from the Pakistani Taliban. “We need to face and acknowledge the facts: The country is in a warlike situation, and we are in a conflict zone,” Khan told the National Assembly. (Tim Craig and Shaiq Hussein, The Washington Post, June 10)

In the last few years, the Pakistani government has been more noticeably engaged in the fight against militants in the FATA. Last November, Islamabad began implementing new policies and laws, some resembling the United States Patriot Act, in an effort to stem the tide of insurrection and insurgency. Days after the attack on the airport in Karachi and just prior to the Pakistani military offensive launched this past Sunday, I examined an editorial article at Foreign Intrigue. In the article, I paid specific attention to a piece written in Newsweek Pakistan on June 8th that offered complexity to the argument for the Pakistani government’s pivot toward a more aggressive posture in dealing with militants, insurgents, and international terrorist elements that have secured haven and operational cover in Pakistan.

Writing for Newsweek Pakistan, Khaled Ahmed wrote of changing policy and the hardening stance of the Islamabad government towards the fight against insurgents and international terrorists in the FATA. Titled “Fighting Pakistan’s War”, Ahmed makes several important points about the necessity of re-examining Islamabad’s preference for negotiations with insurrectionists such as TTP and The Haqqani Network. With specific regard to the latter, Ahmed posits that a fundamental change in priorities in the relationship between Islamabad and The Haqqani Network is necessary. As is often the case in international relations, the impetus for that change in priorities is a conflation of economic and security interests:

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

There are rumors afloat that Pakistan is about to ditch the Haqqani network (which represents the “good” Taliban). The first sign of this came last year when Nasiruddin Haqqani, the group’s chief fundraiser and alleged liaison with the Pakistani security establishment, was gunned down near Islamabad.

The Pakistani Taliban, linked with the Haqqani network through Al Qaeda, blamed the murder on the Inter-Services Intelligence agency. If this report is correct, some irony will be rubbed off from the statement Prime Minister Sharif made at 10 Downing Street on April 30 to his British counterpart, David Cameron: “Pakistan will not allow its land to be used against any country.” He got back a very pregnant answer from Cameron: “The enemies of Pakistan are my enemies too because we want to defeat the extremism, the terrorism that threatens your country and so many others in the region.”

Appropriately, in the background, in the typically rowdy British parliamentary style, lawmakers demanded that British aid to Pakistan be terminated unless it can be proven that the funds are helping stop Islamic extremism. Pakistan is the largest recipient of British aid; Islamabad is set to receive £446 million this year alone. The U.K. is giving funds to Pakistan not only for not exporting terrorism (through groups like the Haqqani network), but also for stamping out extremism in Pakistan that threatens the U.K. through its vast Pakistani expat population. Pakistan is in dire economic straits.

This could be a blessing as there is hardly any other internal persuasion to end extremism and act against the Taliban and the Haqqani network. But some Pakistani legislation, like the blasphemy laws, is so extreme in religious discrimination that it may not be able to find a conceptual basis for opposing extremism. (Ahmed, Newsweek Pakistan, June 8)

On the point of incentive, Ahmed does well to highlight the interests of both the British (security) and Pakistani (economic) governments in targeting militant groups operating out of the FATA. Specifically, an interesting change in recent weeks has been Islamabad’s decision to eschew negotiations with TTP and conduct military operations to root out and destroy the networks of insurgents throughout the Tribal Areas.

Ahmed concludes that in order for Pakistan to stabilize Pakistan’s security (thus ensuring the future of Pakistan’s potential economic viability), the Pakistani military must be the driving force behind destroying the capabilities and threat of the myriad militant networks in the FATA. More specifically, Ahmed (in context of the past decade of militant fundamentalism in Pakistan,, somewhat bravely) asserts that a second prong to the effort in battling the militants in the FATA is for Pakistani government (and society) to re-examine the premise that prioritizes India as the prevalent and unmitigated threat to the country over that of the militants:

The solution to the problem of terrorism driving investors away from Pakistan and causing its own capital to flee abroad is not more talks with terrorists, but a resolute use of force to recapture the writ of the state. This resolute force will have punch if not distracted by the “geopolitical” factor in foreign policy, dividing the Army between two fronts. Pakistan may be at a crossroads today; and it looks as if it is going to make the right policy choice. A reversal of the India-centric worldview will make Afghanistan safe for Pakistan; and the opening up of trade corridors will transform the landscape of terror into economic engagement through massive infrastructural development. (Ahmed, Newsweek Pakistan, June 8)

The apparent willingness of the Pakistani military and security forces to take the fight to insurgents that have securely fastened themselves to the Tribal Areas through a poisonous mix of tribal affiliations is burgeoned by two important variables: the political support borne of the inclination of the Pakistani public to reinforce the fight in the wake of multiple attacks in infrastructure and the population and the existential threat the militants pose to the future of the government in Islamabad.

On the former point, the Pakistani population, wrought with weariness after more than a decade of insurgent attacks on infrastructure and citizens, has signaled its support for the fight. Commentators have noted the value of public opinion and how public support for the military’s mission in Pakistan remains a pillar of its long term success. Early reports in the nascent Pakistani military effort in the FATA are heartening for its ability to affect both the wider international effort against terrorism (especially in Afghanistan) as well as the mission to ensure the future of the Pakistani government in Islamabad.

The Pakistani military forces are a key component in the overall mission to destroy international terror networks. The end state of the multi-national effort remains the collapse of international support networks and havens for Al Qaeda and its subordinate myriad of insurgent groups in the FATA.

(Featured photo courtesy of Narayanese and Wikimedia Commons)

COMMENTS