Human trafficking is alive and well in the United States. We don’t have the labor camps, child soldiers or prostitution rings that some countries do, but many of these things do exist within our borders and in certain places they even flourish. To think that we have moved beyond such things is a stark denial of the truth — it happens in major cities, and it happens in small, rural towns.

Perpetrators range from illegal immigrants to a literal American cheerleader pimping out her own teammates. Recently, I went the International Association of Human Trafficking Investigators (IAHTI) conference. They made it abundantly clear that there is no way to accurately profile human traffickers, and that doing so may cause the investigator to possibly miss a culprit who doesn’t fit whatever idea of perpetrator they had made up in their heads. The cheerleader story is a prime example of that.

First of all, human trafficking can cover a couple of different areas, so it helps to have a clear definition of what it really means. The FBI calls it a “form of human slavery” that includes, “forced labor, domestic servitude, and commercial sex trafficking.” They point out that it, “involves both U.S. citizens and foreigners alike, and has no demographic restrictions.”

The Department of Homeland Security defines it as such: “Human trafficking is modern-day slavery and involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act.”

Labor Trafficking

When most people think of human trafficking in the U.S., they probably think of sex trafficking. This is a huge problem here, but it’s not the only one — forced labor cases are actually more common than you might think. In recent years, Guatemalan teenagers were smuggled into the United States to an egg farm in Ohio. There they were forced to work in austere conditions — no running water, long work hours, and little to no pay. Their lives and the lives of their families were threatened (the traffickers had ties back to Guatemala), and the entire work environment was fear based.

Labor trafficking can take a few different forms — like with the Guatemalan teenagers, they might start with promises of foreign education and (relatively) high amounts of pay, then take advantage of poor families, using fear and force as primary motivators. Fraud and coercion were other motivators.

The idea of “debt bondage” comes up a lot in U.S. trafficking schemes. People are somehow tricked or forced into an immense amount of debt, and then forced to work that debt off with the promise of one day being free. Of course, that promise is most often never brought to fruition — imagine owing someone $30,000 and then making 10 cents an hour while living under their oppressive thumb.

The labor is not only agricultural — other cases have been unearthed in the fishing, fashion, forced begging, and domestic labor industries (domestic labor would include a cleaner or a nanny).

However, sex trafficking finds its way to the news more often because it is more common in the United States. In a study conducted by the National Institute of Justice, 11% of trafficking cases involved only labor trafficking, and 4% involved both labor and sex trafficking combined. Still, it’s important to remember that studies like these are based on law enforcement action, and, by definition, if the traffickers are successful in their endeavors then their organization will never reach law enforcement surveys. Due to this secretive nature, it’s difficult to really determine accurate numbers across the board in the United States.

At the end of the day, the National Institute of Justice says that, “the Department of Health and Human Services has seen a steady rise in labor trafficking victims, and nongovernmental organizations have reported increasing instances of traveling sales crews and peddling rings using child and adult forced labor in the U.S.”

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Sex Trafficking

Sex trafficking can mean a pimp in a major city forcing prostitutes to perform sexual favors for money; it can also mean an abusive boyfriend using his girlfriend for the same purpose, and doesn’t necessarily have to involve some shadowy criminal organization. And of course, it can also involve a cheerleader using her fellow students. These cases range in all sorts of possibilities, but they all boil down to someone being forced (be it by physical force, blackmail, coercion, or some other form of manipulation) to perform sexual acts for a profit.

In a case I recently covered, one woman had been working at a country club with her friend. Her friend said she was making money on the side doing adult webcam performances, and invited her to join and make some money. Little did the victim know, the other woman was being forced by her boyfriend (via multiple methods, primarily by threatening her son) to perform these acts, and he had directed her to convince the victim to tag along. Thankfully, the victim decided she was uncomfortable with it during their first session and left before he was able to rope her in; unfortunately her friend would have to suffer much more before going to the authorities — who eventually put the man behind bars for over three decades.

That’s not to say that organized trafficking is not prevalent throughout the United States. Organizations will lure and trap both children and adults into organizations, forcing them to sell their bodies for a profit. As the Atlantic outlined in a well-written account here, these victims can be quite ordinary people before they are roped into something they don’t fully understand.

According to the National Human Trafficking Hotline, there were 6,081 cases of human sex trafficking in 2017. Between the years of 2012 and 2017, they recorded 25,168 cases. That’s a fraction of what really goes on, and does not include all of the cases that go unnoticed, nor does it include combined cases of labor and sex trafficking.

A staggering number of these cases involve children. According to the National Center of Missing and Exploited Children (NCMEC), approximately 14% of the missing children reports they documented were confirmed victims of child sex trafficking. That’s one out of every seven. Of those children, 88% were in the care of social services. The NCMEC representative at the IAHTI conference said that traffickers prey on kids’ weaknesses, and that “simply being a child makes you vulnerable.” They said that the average age of these trafficking victims is 15 years old.

This does not even begin to delve into the prevalent issue of international sex trafficking and subsequent problems like sex tourism.

~ ~ ~ ~

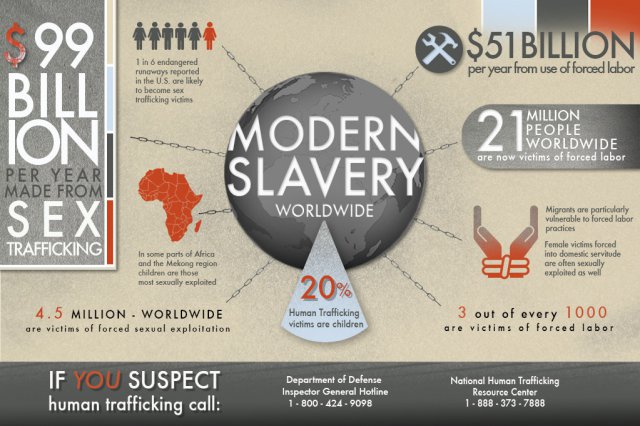

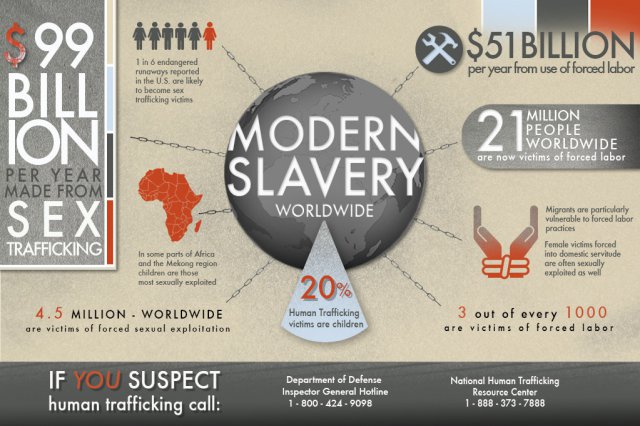

For more statistics on human trafficking in the U.S., check out the statistics page from the National Human Trafficking Hotline here. The infographics are very informative and easy to read.

To get a very basic idea of the global problem of human trafficking, check out this infographic courtesy of the U.S. Army:

Featured image courtesy of Pixabay. Sex trafficking image courtesy of Ira Gelb on flickr, here. Labor trafficking image courtesy of pxhere, altered by the author.

COMMENTS