It was February 3, 1780 out in rural Connecticut. Barnett Davenport, a veteran of the American revolution, beat a man and his wife to death, and then burned their home with their three grandchildren inside. The grisly homicides captivated the minds of a brand new America, horrified at the actions of one of their own.

Davenport had a troubled past — he was a thief from an early age and seemed to often go against the grain.

He wrote a brief life story and confession, though the author admittedly altered it: “The narrative is penned from the criminal’s mouth, though not always exactly in his own words. Some moral reflections are interspersed,” and you can see that with the heavy emphasis on profanity and stealing, rather than maybe the fact that he was a very heavily experienced combat veteran of the Revolutionary war, and also most likely a serial killer.

As they tell me, I was born at New-Milford, the 25th of October, 1760, and lived with my parents until I was about nine years of age. By this time, I was become quite expert in using bad language, having been accustomed to profaneness, from the time I was capable of forming articulate sounds … But there I began to pilfer, by stealing green corn, which was, (if I rightly remember) the beginning of that infamous practice, which led me on to the most horrid crimes ever committed.”

You can see the moral lessons “interspersed” here — stealing corn was apparently a gateway drug into mass murder.

Davenport was also an experienced soldier, having fought in Ticonderoga, Hobartown, Valley Forge and Monmouth — to name a few. Just reading this excerpt, you can see the “interspersed” moral lessons about stealing, and the total disregard for the effect a war can have on a person. Some may go so far as to attribute his actions to severe, undiagnosed PTSD. While most wouldn’t try to argue that this was some kind of excuse for his actions, it could have been a contributing factor, or at least ought to be recognized. Regardless, this next excerpt is a good example of how little people realized that a series of traumatic events can have any effect at all on a person:

Early the next spring, I went to Danbury where I kept guard two months; during which, I stole hens, geese, Continental rum and wine. From thence I went to Valley-Forge, and joined the army; but on the road stole some sugar; was at the battle at Monmouth; remained with the army till General Patterson’s brigade, to which I belonged, came to Woodbury, the October following.”

Early the next spring, I went to Danbury where I kept guard two months; during which, I stole hens, geese, Continental rum and wine. From thence I went to Valley-Forge, and joined the army; but on the road stole some sugar; was at the battle at Monmouth; remained with the army till General Patterson’s brigade, to which I belonged, came to Woodbury, the October following.”

The emphasis here is quite obviously on stealing and nothing else. Let’s focus on sugar theft, never mind the battle that killed over 2000 American soldiers, or the other battle that killed up to 500 Americans.

Though it’s important to understand why criminals do what they do, that does not excuse or dismiss what they did. Davenport was reportedly unprovoked when he did one of “the blackest crimes that ever mortals committed.” He said he did it “merely for the sake of plundering the house,” though murder seems a bit harsh and honestly more difficult than simply stealing and running off. He admits that “I was haunted and possessed with the thoughts of murder, from the time of my first entertaining them, both day and night,” making his reasonings quite clear.

And he describes the events here:

On the 3d of February, she went away accordingly, and tarried that night—A night big with uncommon horror. My heart trembles and is moved out of its place, at the relation of this most tremendous, cruel, bloody, and amazing scene.—Mr. Mallery and his wife with one of the children, went to bed in the same room—he lying in one bed, and the other two in the other. Upon this, I took a piece of cloth and made me a knapsack: and then went to plundering the daughter in law’s room, searching for some hard money, which, I understood she had, but could not find it. After putting some things into my knapsack; with the candle in one had and the swingle in the other, I went into the room where Mr. Mallery, his wife and one grand child lay asleep. First I smote him with my might once or twice on his head; upon this Mrs. Mallery awaking attempted to rise up; I turned and struck her one or two blows. Mr. Mallery then sprung up; I struck immediately at him; but he partly warded off the blow with his arm, and then struck the candle out of my hand; I then pushed him back, and down upon the bed, belabouring him with the club—He asked me who I was? what I meant? and said, tell me what you do it for? Then called to his wife to come and help him repeatedly. Who can abstain from tears, while relating these things! Mrs. Mallery made no answer, only shrieks, cries, and doleful lamentations. Having for some time smote Mr. Mallery and pounded him, the swingle split. Upon this, I catched a gun which stood behind the door, and with this instrument of death, proceeded still to smite him: I then turned again, and did the same to Mrs. Mallery, and continued striking till she lay still as well as he.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

The child, in bed with its grand mother, was seven years and eight months old. These cruel blows and piercing cries awoke the tender babe, in shocking surprize, even while I was killing her grand father; and starting up she asks, her dear but wounded grand mother, what is the matter. She cried out bitterly; she called out for me, or to me, by the name, the pleasant child used to call me, saying, Mr. Nicholas. But I continued paying on; feeling no remorse at killing my aged patrons and benefactors. For the child, I seemed to feel, some small relentings, without remitting in the least, my execrable exertions. This anger was cursed, for it was most barbarous and cruel.

Probably this child was at this time mortally wounded; for she gave a few terrible shrieks, which (one would think) were enough to pierce the hardest heart, and reach the center of the most obdurate sinner’s soul: And then she lay still, sighing and groaning in the most affecting manner.

The room being now besmeared with blood, and filled with horrendous groans: I went into the other room, lighted the candle, and presently returned to this room, in which expiring groan answered to groan. Nor was Pharaoh’s heart harder than mine For amidst these dying groans and streaming blood, I looked for the key to open the chest where the money lay; but could not find it. Then I went, got a pestle and broke open the chest. By this time both Mr. Mallery and his wife began to struggle—I mashed his head all to pieces with this instrument: And she rising partly up in the bed, I smote her also with the pestle on her head, several times, and she tumbled behind the bed. Before this I saw her face swoln to twice its common bigness, disfigured with wounds, and covered with gore and streaming blood.

After all this he set the house ablaze and all remaining souls inside were lost.

The obvious connection here is the still emerging field of serial killers, their fascination with death, and other proclivities toward bloodshed. It was only recently that the FBI classified serial killers as such, and up until then they were just described as homicidal killers who were full of sin or malice, simply just because that’s the way they were.

And in the final paragraph, he proclaims his fate (which has surely also been edited):

On the 27th, sentence of death was publicly pronounced; and, upon the eighth of May next, I am to be executed. O that others may take warning by my dreadful example and fearful end! And avoid those sins which I have committed, and which by a series of wickedness have led me on to the most awful crimes that ever were perpetrated in this land, or perhaps any other; and for which I must (most justly) suffer a violent death, and I greatly fear, everlasting burning, horror and despair.”

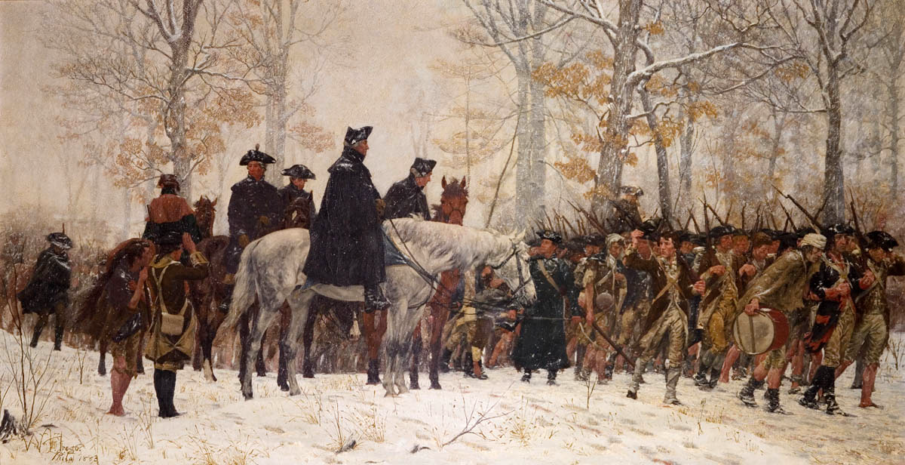

Featured image: Painting depicting George Washington leading the Continental Army to Valley Forge in 1777.

All images courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

COMMENTS