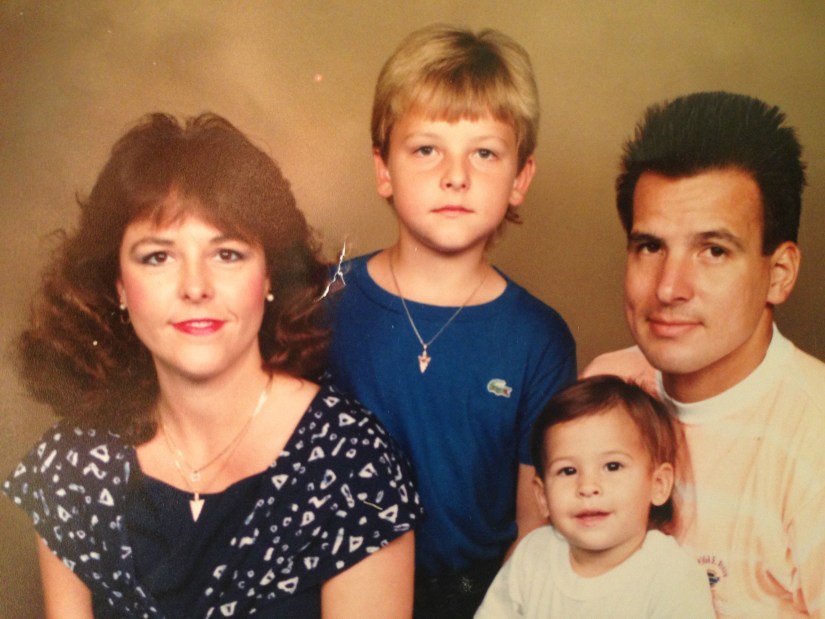

Written by Shayne Carlson. I cannot say how many people have talked to me about my father, “Chief” Carlson. Whether they knew him personally at some point during his extensive military career, or just knew of him through national news as an idolized figure in special operations, they only knew of him as a friend or professional. As his son, I am unable to contribute to who he was in his professional life. What I am able to do is expand upon who he was as a father and husband. I had a deep emotional connection to my father since birth, to which my family has many supporting stories.

For instance, when my grandmother would babysit me during her visits to Okinawa, Japan, she would think that my connection to her couldn’t get any better. This castle would soon crumble as she would witness me light up in a manner impossible for her to reproduce when I would hear Dad’s car pull up in the driveway. My mom told me another story of when I was two. When Dad’s team returned to the local airport from training or deployments, we would wait behind a chain-link fence until he was cleared to leave.

The second I saw Dad get off the plane, though, I was done waiting. Mom had to physically pull me off of the fence before I made it over, all the while yelling, “DADDY! DADDY!” Dad and his teammates found this hilarious. My earliest memory is of my father in Fort Polk, Louisiana, where he had a Special Forces observer/controller position. I was three years old and Dad was placing me on his back as we swam in the nearest lake. When he’d stop to rest and play with me, I’d only scream, “more!” not realizing how difficult that must have been. I remember feeling so safe and loved.

My other prominent memory from Louisiana didn’t make me feel safe as much as it made me feel pain. I was probably four years old at the time. My dad, brother, and I were playing in the neighborhood park. Dad was spinning me on the merry-go-round to the speed of my request. “Faster! Faster!” I continued to scream until my body was completely horizontal, like a flag in a hurricane. My little hands were holding onto one of the bars as tightly as I could. One wrong move and Dad could have broken his hand. “Faster! Faster! Faster!”

My repetitive request was brought to a sudden halt as I was flung from the contraption. I opened my eyes to Dad hovering above me, helping me up after experiencing what may or may not have been a concussion. Beneath his concern I could tell he still found it pretty funny. I could tell because he was laughing while he was helping me.

Speaking of concussions, my older brother, Shaun, has a funny memory of Dad before I was born. Shaun was present as Dad was doing a training static-line jump in Savannah, Georgia as a Ranger. One of dad’s buddies was watching out for Shaun while our dad was part of the fascinating spectacle of men falling from the sky. Imagine that through the eyes of a five-year-old. Instead of witnessing his hero come in for a graceful landing, Shaun witnessed Dad land in a cluster of trees near the landing zone, knocking him unconscious for a noticeably long time.

Regardless of the talk Dad and Shaun had on the way home, Shaun busted in the door yelling, “Daddy was sleeping in the trees!” Dad responded, “That was supposed to be our secret!” Beyond the innocent blurting of a pre-schooler, Mom more than likely would have never found out about this near-death experience and how her son was a direct witness.

Having such an impressive figure for a father, and one who was gone as much as he was home, I was naturally very curious about what he did. Probably around the age of seven, I would start to ask questions, usually while we were on a drive together. Every single time, it went something like this:

“Dad, what do you do when you are gone?”

“I work.”

“Well, yeah, obviously. But what is work?”

“It’s what I do.”

“What do you do?”

“I work.”

“What is work?!”

“It’s what I do.”

This would continue, his smile growing with my frustration, until I invariably gave up. I probably only initiated this conversation three or four times before giving up altogether. He would also use this never-ending loop technique when I would ask the typical annoying child questions like, “How much farther?” His response would be a simple, “We’re closer.” I would counter by saying, “You’re not answering my question. We’re closer with every step (or second if we were in a car).”

“Yep,” would be his response, accompanied by a half-smile. Dad definitely had a quiet and playful nature, which was mischievous at times. He never really had serious talks with me, and he didn’t have to. He had a way of giving me ideological life advice in passing and when it was called for.

As an outdoor educator today, I can clearly relate this to a modern teaching method called “teachable moments”—pretty much letting present circumstance do the teaching for you (i.e. explaining energy flow when you see animal poop on the trail, explaining the different organisms involved in decomposition after “stumbling across” a decaying animal in a meadow, etc.). There are a couple of these moments that Dad capitalized on that are engrained in my brain almost 20 years after the fact. Interestingly, they involve the respect for living things and nature. When I was around nine years old, I was helping Dad clean the yard. We were putting limbs in a wheelbarrow that he had cut with a chainsaw. A spider revealed itself in the wheelbarrow and I squashed it.

“Why did you do that?” he asked. His concern confused me.

“I don’t know. It was a spider.”

“Was it hurting you?”

“No.”

“Don’t kill anything unless you are defending yourself or someone else,” he said as he looked me in the eyes. He didn’t say anything else. He didn’t have to. He just kept working.

On hikes I take kids on today, every time I see a student intentionally step on an ant, I try to reenact this moment. Hopefully it sticks for them as well is it did for me. Another quick but important lesson involved my preconception of what it meant to be a man. Besides Dad’s mom, we only interacted with my mom’s side of the family in Georgia. That said, both my uncles and cousins in Georgia were hunting enthusiasts. Since I was raised in North Carolina, I was unable to participate in their hunting expeditions.

When I was 12, which is when Dad taught me how to shoot a pistol, I started to become envious of my cousins, as well as my school friends in North Carolina. They all had exciting stories of hunting wild animals and they had the prey’s heads to prove it. I mean, my dad was one of the best soldiers in the world; he had all sorts of training and skills in weaponry, tracking, and orienteering. I had Native American blood, for God’s sake! These whities don’t even know that they don’t know what they’re doing. If he taught me how to hunt, my friends and family would covet my skills and stuffed trophies. Once I decided to express these feelings to Dad, I half expected him to be elated about my willingness to pursue “manhood.” Instead, his response was, “You shouldn’t kill anything unless you have to. We have all the food we need, so you would be killing an innocent animal for no reason.”

That was it. Conversation over. My preconception that hunting wild animals made you a man was quickly changed. Teaching world concepts with ease is one thing, but teaching physical skills is another. Dad would go out of his way to teach us skills efficiently and in a unique fashion. One instance that comes to mind is when he was teaching my brother how to drive. Dad was home for a short while before he had to deploy during the time Shaun would receive his driver’s license. Instead of making sure Shaun could efficiently drive Mom’s automatic vehicle, he taught Shaun how to drive his manual transmission Jeep Wrangler. On top of that, he made sure Shaun was capable of pulling and backing up a trailer in said Wrangler. Shaun accomplished this crash course in one day. That was a long day. As an unexpected reward, Dad brought home a pair of night vision goggles and let Shaun drive us around our neighborhood by starlight.

As I watched my brother drive us through darkness with Dad in the passenger seat, apart from my mind being blown, I felt a strong sense of love and luck to have a father like “Chief.” Dad was nothing short of exceptional when he taught me how to shoot a pistol, too. He actually obtained an exclusive membership to a local gun club in Southern Pines, North Carolina. There was about a two-year waiting period to get that membership, so he either planned ahead or pulled some strings. The only reason he did this was for access to the target range so he could teach me and my brother how to shoot efficiently. He was a great teacher, and we would soon start to have friendly competitions with each other. I’m proud to say that I could actually hold my ground against him. The fact that I would shoot a .22 with a red dot scope in both hands, and he would shoot a .45 with only his left hand is irrelevant.

The shooting wasn’t the only thing I looked forward to on these outings; Dad made the drive there exciting as well. After the padlocked gate entrance, there was a dirt road that went for about a half mile before reaching the shooting range. I forget how this ritual developed, but after we got past the gate, I would climb onto the roof of our Ford Explorer. From there I would get into my best surf stance and tap on the top of the roof, giving him the cue to start my ride. It was hard not to enjoy every moment with him. He was a great father.

In addition to his natural teaching ability, he was incredibly talented in many areas. I was constantly reminded of this. He was surprisingly good at drawing; way better than what I would expect from the very few times he would sit down and sketch. He once helped me for an art project in 6th grade on a 2×3′ pastel replica of Vincent van Gogh’s self-portrait—the one with the bandage over his missing ear. He helped me greatly with the general outline and dimensions, as well as with the mixing of the colors. The one thing he did completely by himself was the eyes, which were a beautiful mixture of different shades of blue. When I turned in the finished product, the art teacher was so impressed, she asked me if she could put it on display at the local public library. “Of course,” I said, full of giddiness and pride in my superior artistic abilities. She then went on to say, “This whole picture is amazing, but the one thing that sets it apart is the eyes. They are just mesmerizing.” My pride turned into humility, as well as an inner explosion of laughter for being recognized for the one thing I didn’t do at all.

My brother and I succeeding in school was a priority for Dad, but sometimes his sense of humor would offset that. For example, when I was about 10, I had an assignment to write a fictitious short story in first-person perspective. When I asked Mom and Dad for some initial assistance, Dad began to reminisce on similar assignments he’d had for school.

“I loved doing this. It was the best time to freak the teachers out.” He began to talk in the tone of a gritty 17th-century sailor: “The date is June 10th, 1645. This morning, we ate a member of the crew.” Mom told him not to encourage me.

Dad had a strong sense of humor, and he wasn’t afraid of anyone or anything, so authority figures were not safe from his teasing. This would actually lead him to not be accepted into an elite Special Forces detachment on his first attempt. Apparently the psychologist didn’t find his disturbing responses for the sake of humor very funny during the mandatory psychological evaluation. Maybe that’s because Dad never told him he was kidding, which was the funniest part to him. He played it right on his second attempt and got in—no problem.

Another story comes to mind that one of his teammates told me. When Dad was an Army Ranger, he and a higher-ranking individual had to drive a long distance throughout the night. Dad didn’t have a lot of respect for this guy’s character; he made Dad drive the entire distance while he caught up on some sleep.

Instead of grumbling under his breath like some people, Dad would swerve the car several times throughout the night, causing the sleeping “superior” to slam his head against the window. Each time he was painfully awakened, he’d ask what the heck that was about. Dad would disguise his laughter by blaming it on a variety of woodland Georgia animals.

“Sorry, man; it’s like a damn zoo out here. Jeez.”

I would soon adopt his stance on authority and humor, although in a less subtle manner. In sixth grade, my science class had individual assignments to present information on the planets of our solar system with a PowerPoint slideshow. I tried my best to keep my composure as I raised my hand and requested to present the planet Uranus, my head swimming in all of its hilarious potential. As my class quietly worked on separate computers, I could hardly contain my laughter as I composed a series of suggestive graphics involving spaceships and planets for my presentation entitled, “Let’s Get it on With Uranus.”

My plan for the best presentation ever was thwarted when my teacher noticed the cluster of students hovering over my shoulder. My teacher worked with Mom at my school, so I would eventually find myself in my parent’s bedroom for a talk. While Mom scolded my childish humor, Dad didn’t have much to say, although he did periodically squint his eyes and give a quarter smile, which I could tell was his attempt to keep himself from laughing out loud. Dad’s subtle encouragement of fearless humor would nearly lead me to get my high school diploma withheld. At the rehearsal for an honor’s program ceremony my senior year, we were to practice receiving a “cord” on stage. Here we wrote down the colleges we were going to attend and our major for the orator to announce before we walked across stage. To my amazement, the organizers of this ceremony did not bat an eye when I turned in my information stating that I was going to attend UNC-Wilmington with a major in “magic,” inviting me to capitalize on this rare moment.

On the day of the ceremony, when my name was called to walk across the stage to receive my reward for academic success, the elegantly tongued orator stated calmly and professionally into the microphone, “Shayne Carlson, son of Cheri Carlson, is going to attend University of North Carolina at Wilmington, and is pursuing a major in magic.” I received the cord to then turn to the crowd and show off my rehearsed magic “skills”: making my thumb “detach” and slide up and down my hand, and then linking my fingers together as rings, separating them behind my back. I was told that the elderly financial donors sharing the stage looked like they were going to have simultaneous laughter-induced heart attacks. The principal didn’t find this very funny, though, and called me into her office a week before graduation to threaten my diploma if I conducted any antics on graduation day. Dad wasn’t alive at the time, but some of his teammates who had sons or daughters at my school thought this was hilarious.

Dad’s presence was unmistakable, and even after he was killed, my family has experienced the strength and love of his spirit on multiple occasions. If I didn’t believe in spiritual encounters before Dad died, I did after (feel free to have your own opinions on the following stories). I was 21 years old, seven years after his death, and went to Dad’s work on a family day at their gym. On these days, dependents of detachment members could train with the combatives instructors. For some reason or another, I was uninformed that it was President’s Day, so they would not be instructing. I was very surprised to show up to a dark, vacant room. I decided to take advantage of the time I set aside to train and worked out by myself, swinging kettle bells, jumping rope, beating up on Bob the dummy, then grabbing a shower before leaving.

On the way to the exit, there was a set of doors opening to the memorial courtyard where there’s a wall containing names of former and active detachment members who had been killed in action. I hadn’t visited the courtyard since his name was engraved into the wall seven years prior, when he was killed. I never had any desire to do so, knowing it would conjure up painful memories and “what-ifs,” undoubtedly ruining the rest of my day. For some reason, at that moment, walking by those doors, I felt like it was time to visit the wall and touch Dad’s name. I took a deep breath and walked into the courtyard to approach the wall.

As I stood at the wall and stared at Dad’s name and date of death, reading “MSG William F. Carlson, 25 Oct., 2003,” I began to take in the 20 or so other exceptionally brave and intelligent men who had died since the detachment’s creation. I thought about their parents and probable wives and children. Then I began to take in the three or so names engraved below Dad’s—the most recent additions. I began to feel something I didn’t expect; I began to feel honor, peace, love, and luck to have such a great father who was a part of something monumentally bigger than him. I felt calm in a place that I expected to make me crumble. After a few minutes of tranquility beyond what words can convey, I touched Dad’s name one last time and turned around to leave the courtyard. What I saw took my breath away.

In the fluorescent lights, I could see that it was just beginning to snow. In the Sandhills of North Carolina, snow is a rare occurrence; it maybe happens once a winter. Also, snow had not been forecasted, which is even rarer. Call it a coincidence if you’d like, but in that moment, I physically felt his presence.

The most recent occurrence happened last year, shortly after my brother had his first child. My mom and my brother actually work at the same hospital, and a few weeks after his son was born, Shaun brought him into work to show him off to their coworkers. As the new baby was passed from one person to another in Mom’s second-floor office, a beautiful hawk flew up and landed on Mom’s window ledge, casually and curiously peering in. As Mom, Shaun, and many others surrounded the window to take pictures, the hawk was unfazed by all of the commotion and continued to peer in. Mom and Shaun could not help but volley glances between each other, assuming that this beautiful, wild creature could possibly be guided by Dad. Just maybe, he had come to share this experience with his wife and son.

Dad’s proud Blackfeet Indian heritage, along with his warrior mind, body, and spirit only make these experiences more tangible. This makes the last story I am going to tell my favorite. After Dad was killed, a number of family and friends began to stream in and out of our house to show their support and help us in any way they could. Along with that constant cycle of new faces and names came a few elders of the Blackfeet Indian reservation who personally knew Dad. A couple of them actually taught him Blackfeet traditions and ceremonies. One in particular, whom I called Uncle Patrick, had beautiful, long, dark hair and a deep but humbly soft-spoken voice—rich in a Blackfeet accent. As a direct representation of the proud Blackfeet Nation, he was an enchanting figure to say the least. He paid tribute at Dad’s funeral by singing a tribal Blackfeet song while playing a traditional drum of Dad’s that was displayed at our house.

Although only a few people at that funeral understood the Blackfeet language, the mournful reverence was unmistakable. After Dad was buried in Georgia, Uncle Patrick was soon to fly back to the reservation in Montana. Before leaving, he had a conversation with Mom about what was to become of Dad. He told her that the Blackfeet tradition of grieving is to mourn for seven days and then let their spirit be free, but Dad was an exceptional warrior whose spirit was so strong that he would be back to visit her as an eagle. Mom respectfully listened to Uncle Patrick, but undoubtedly thought to herself, “Yeah, yeah, he’s just saying this to make me feel better.” She wouldn’t think much of this conversation until October 25th, 2004—a year to the date after Dad’s death. Mom was having an obviously difficult day, and was reflecting by herself in her backyard. She was in awe when a bald eagle flew over her head, landing on the boathouse directly in front of her. That was the very first time she had seen it, and immediately knew that her warrior husband had come back to visit her and let her know that he would always love her.

Chief

A poem by Seth Patterson

A family friend

A patriot of no measure

A soldier without fear

A father and a husband to which time with them stood still.

Admired by everyone whose path he ever crossed,

He never took for granted the job to which he had been brought.

Alone at times it might’ve seemed,

through the pain and through the tragedy,

The task ahead seemed much too great for any normal man,

But anyone who’s met this chief would know

that he’s greater than a man.

Forever people will look back on him

and see what he really was,

a soldier and a family man,

but still, words cannot describe

Because there is no greater man

than he who lays his life down for his country.