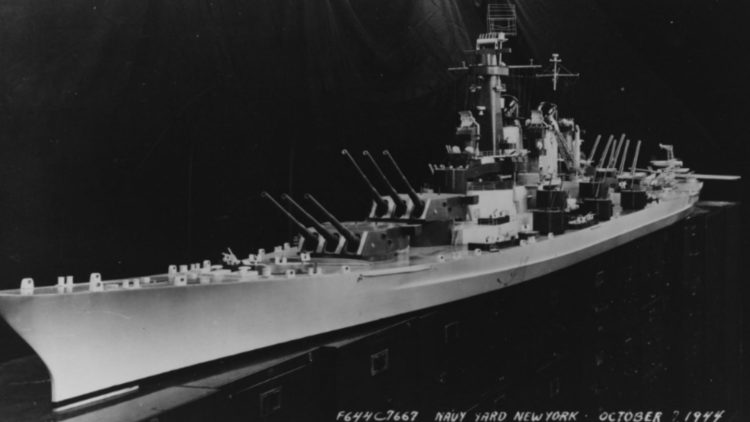

Additionally, their secondary armament included twenty 5-inch/54 caliber guns mounted in twin configurations, providing ample firepower for defending against aircraft and smaller ships.

However, the real standout feature was their armor. The Montana class would have been the only new World War II-era US battleships capable of withstanding hits from 16-inch shells, essentially making them bulletproof against most surface threats. This heavy armor, however, came at the cost of a wider beam, which made them too large to fit through the Panama Canal.

That limitation meant they would have had to sail around South America to switch oceans, a significant operational drawback.

Construction Timelines and Eventual Cancellation

Initially, the US Navy planned to build five Montana-class battleships: Montana (BB-67), Ohio (BB-68), Maine (BB-69), New Hampshire (BB-70), and Louisiana (BB-71). The construction was set to take place at various naval yards across the country, with the first hulls expected to be laid down by the early 1940s.

However, the outbreak of World War II brought new challenges and priorities. Naval battles were increasingly being fought in the skies, with aircraft carriers and submarines proving to be the real game-changers.

The iconic attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 made it clear that battleships, no matter how heavily armed and armored, were vulnerable to air power.

By 1942, it was evident that carriers were the future, and resources were urgently needed for aircraft carriers, amphibious ships, and anti-submarine vessels. As a result, construction on the Montana class was suspended in May 1942 and officially canceled in July 1943.

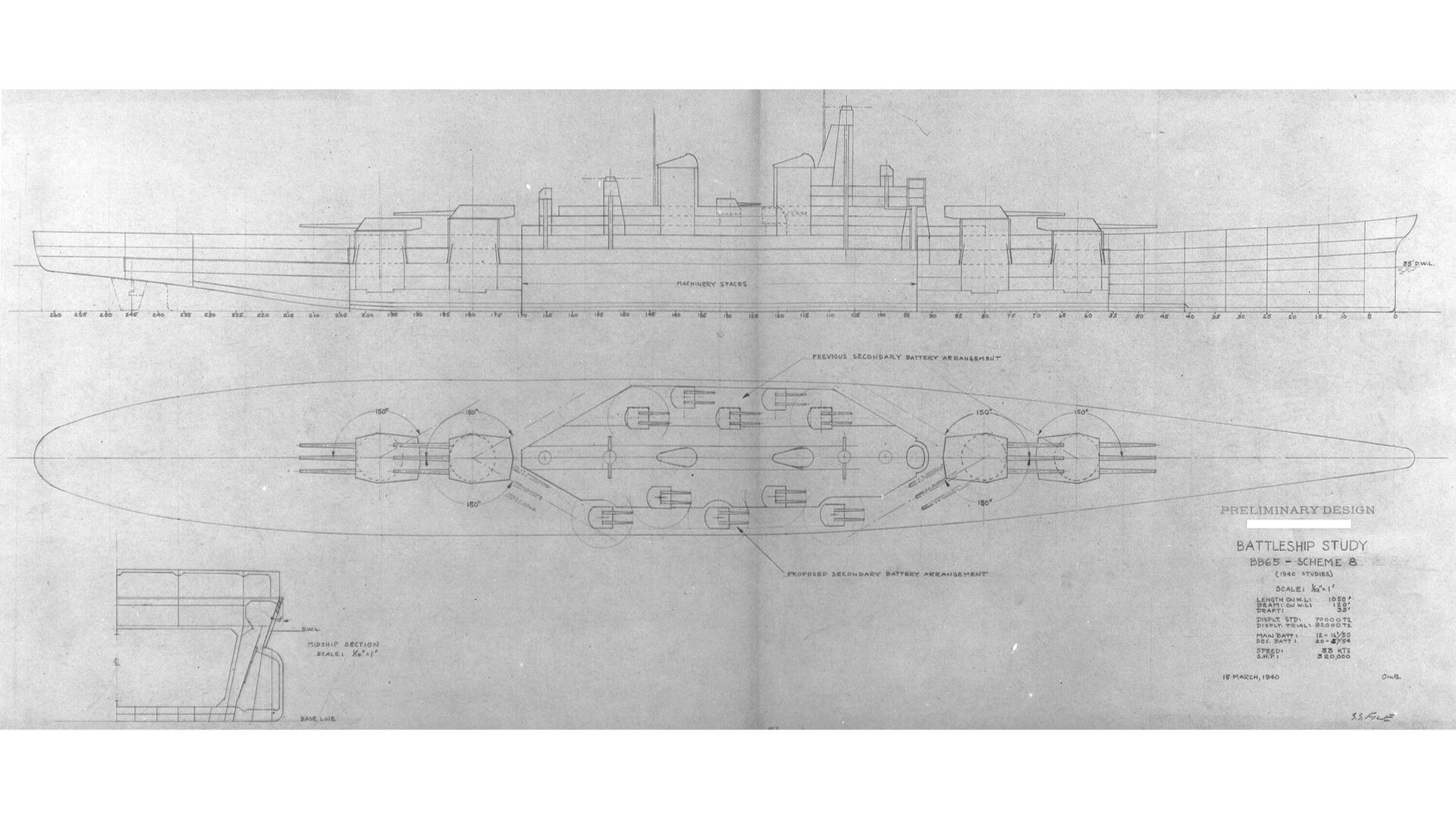

None of the ships ever left the drawing board.

What Could Have Been?

Had the Montana-class battleships been completed, they would have given the US Navy unmatched firepower at sea. Their ability to absorb hits and dish out destruction would have made them formidable players in any surface engagement.

But the truth is, by the time they would have been commissioned, naval warfare had already changed drastically.

The aircraft carrier, with its long-range strike capabilities, had become the dominant force. Battleships, once the undisputed kings of the ocean, were increasingly relegated to support roles, such as providing shore bombardment or anti-aircraft defense.

That said, the Montanas could have found some use in the post-war years, much like the Iowas did.

The Iowa-class ships returned to action during the Korean War, Vietnam, and even the late Cold War, offering heavy fire support and showcasing the value of a well-armored gun platform.

The Montanas, with their superior firepower and protection, could have filled similar roles, serving as floating artillery batteries capable of supporting ground forces and providing a show of force.

Potential Role and Contribution to Today’s Navy

If somehow the Montana class had survived into the modern era, they would undoubtedly be different ships than originally envisioned.

Like the Iowa-class battleships, which were refitted with modern radar, missiles, and electronic warfare systems, the Montanas could have been similarly upgraded to remain relevant. They could have been repurposed for missile defense, equipped with vertical launch systems to fire Tomahawk cruise missiles or even modern anti-ship and anti-air missiles. Their thick armor would still offer valuable protection against threats that modern ships, with lighter aluminum hulls, struggle to withstand.

Yet, even in this alternate history, their usefulness would be limited.

The US Navy’s emphasis on multi-mission ships like guided missile destroyers, submarines, and supercarriers would still overshadow the utility of a super battleship.

In a world where precision, speed, and adaptability are key to naval dominance, a massive battleship like the Montana would struggle to find a role that justifies its immense costs.

The Navy would also still face logistical challenges in supporting such large vessels, requiring specialized docks and extensive maintenance.

The Montana-Class: A Missed Opportunity or a Wise Move?

Ultimately, the Montana-class battleships were a bold idea whose time had already passed before a single keel was laid. They represent a fascinating glimpse into what might have been—a world where the battleship continued to dominate the seas, with bigger guns, thicker armor, and even more imposing profiles. But the reality of naval warfare changed faster than ship design could keep up, and aircraft carriers stole the spotlight.

While the cancellation of the Montana class might seem like a missed opportunity for sheer naval power, it was ultimately a wise decision.

The resources and strategic focus that went into carriers and other versatile platforms shaped the modern US Navy into a flexible and powerful force.

The Montana-class battleships, no matter how formidable, would have been relics in a world that had moved on from battleship supremacy. It’s a reminder that in military planning, as in life, sometimes knowing when to let go is the most prudent choice of all.

Would you agree? Let us know your thoughts in the comments!

COMMENTS