There were others, including the practitioners of “quick kill” shooting, such as FBI Agent Jacob Aldolphus Bryce, aka “Jelly.” He was a member of the FBI’s “Gunslingers,” a group of agents who were specifically tasked to engage heavy criminals to take them down fast. But Bryce did not pass on his skills. There are conflicting reports that he instructed at the FBI Academy, but the Academy itself has no record of this. Another SOE officer, lesser known today but just as formidable, was Colonel Leonard Hector Grant-Taylor, who instructed SOE operatives at a base in Egypt.

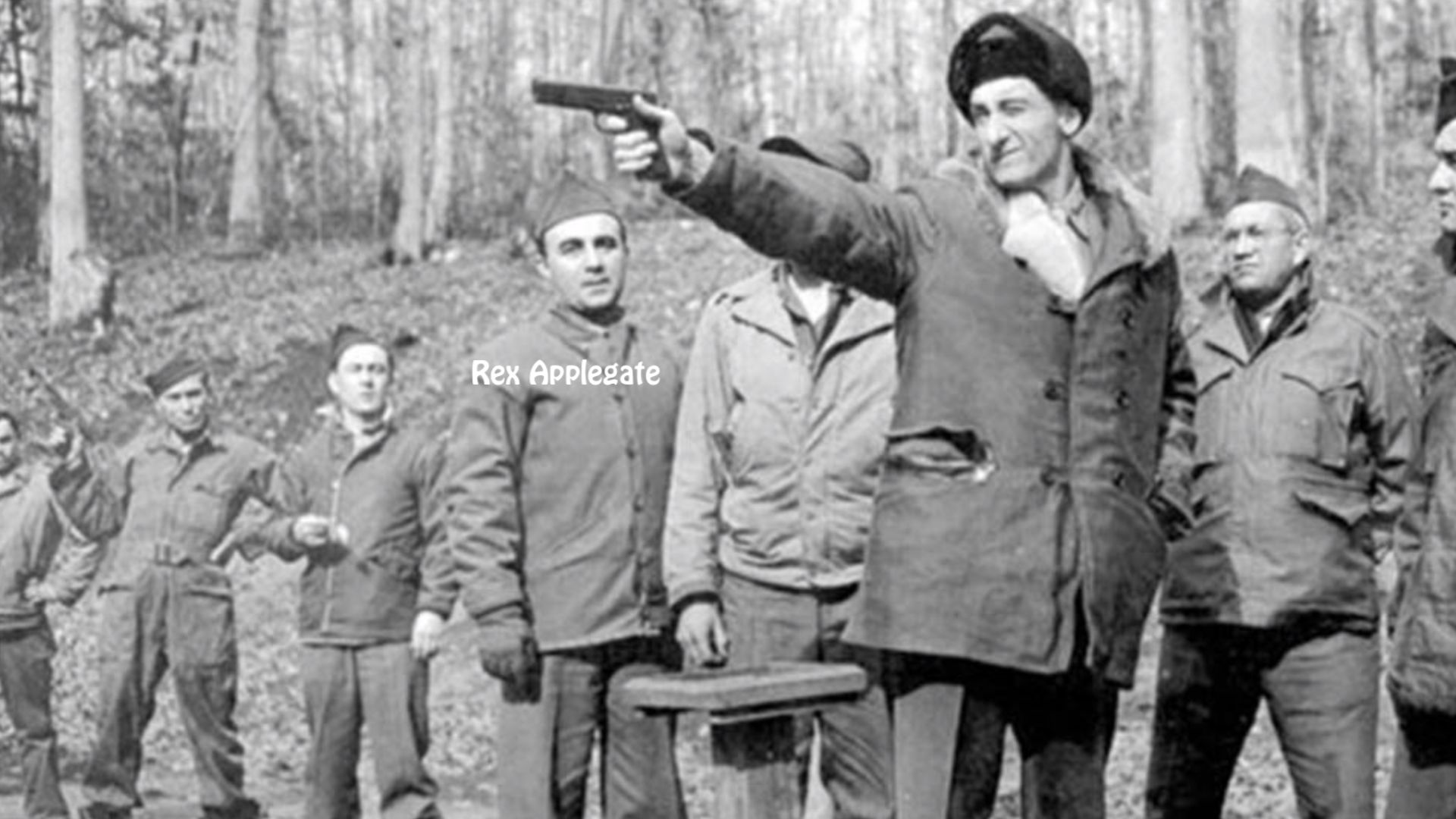

In the United States, with the dissolution of the OSS and the Rangers after WWII, much of the expertise associated with CQB was lost or subordinated to other, less complicated (and easier to teach) marksmanship training. On the whole, the Korean and Vietnam conflicts did not require the same close-quarters fighting skills, although the Marines and Army kept up “quick-kill” rifle training to some degree. In 1990, the USMC even re-issued Shooting To Live, a book written by Fairbairn and Sykes in 1942, as a reference publication called FMFRP-12-81, an indication of the considered value of their skills. The instruction and techniques that Fairbairn, Sykes, and Applegate developed serve as the foundation for modern CQB.

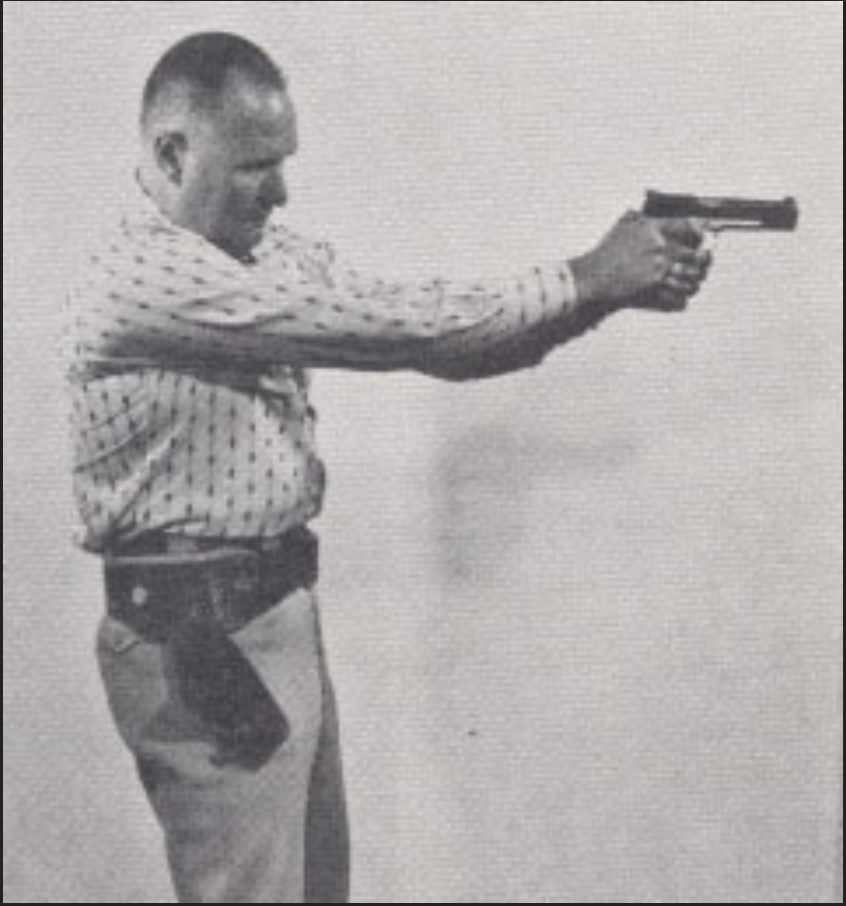

Jeff Cooper is probably the best-known of recent “influencers.” In the 1960s and 1970s, Cooper emerged as the American father of the “modern technique” of shooting. Cooper, a U.S. Marine, developed a style that included the “Weaver Stance,” a two-handed pistol grip used in competition that differed slightly from Fairbairn’s stance. Cooper adapted his from that used by California County Deputy Jack Weaver for shooting competitions. It featured isometric tension through a “push-pull” holding technique. His pet phrase to shooters was, “You hit where you look.” Cooper’s techniques have been woven into practical pistol instruction and adopted by many police units.

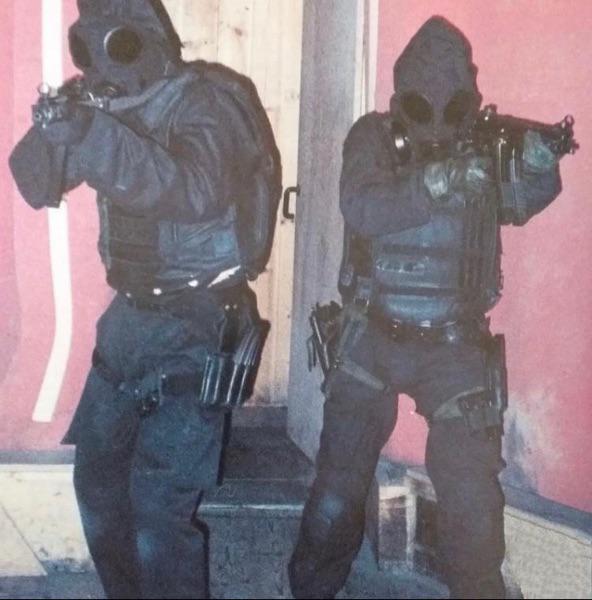

It was the 1970s when CQB began to make its resurgence in the U.S. military, which had already happened in the United Kingdom. The 22nd Special Air Service Regiment’s operations in Aden during the mid-1960s spurred the need to fight an urban insurgency and highlighted the need for tactics to eliminate a terrorist threat that might emerge in the middle of a civilian crowd. That required eliminating the threat without endangering innocent lives. In 1966, the 22nd SAS Regiment started a CQB course to fill that need. Its basic requirement was for an undercover operator (in civilian clothing) to draw his weapon and fire six rounds into a playing card at 15 meters. This was followed by the creation of the Counter Revolutionary Warfare (CRW) Wing, a specialist group of trainers initially created as a response to rising terrorism in Northern Ireland, Europe, and especially the 1972 Munich Olympic massacre in Germany. The CRW was (and remains) responsible for training the entire cadre of operational SAS soldiers in CQB counterterrorist (CT) tactics, as well as selected troopers for Body Guard (BG) operations. Once trained, the SAS Squadrons would rotate to serve in what was first called “Pagoda Troop” and later the “Special Project Teams” on standby for CT incidents. Its first acknowledged mission was the successful 1980 assault of the Iranian Embassy at Prince’s Gate in London, which ended with 19 hostages rescued and 5 of 6 terrorists killed in an 11-minute take-down dubbed “Operation Nimrod.”

In the United States, terrorism had begun to make U.S. Government leadership uneasy. Efforts were launched to form counterterrorism-capable units to combat it. Quickly ruling out military police units as inappropriate, the task fell to the U.S. Army Special Forces. In Europe—the epicenter of terrorist incidents against American interests—Special Forces Berlin was tasked in 1975 to form an “anti-hijacking” capability by the U.S. European Command. Close Quarter Battle would form the core of its initial train-up. Instruction was developed and presented by the unit’s soldiers who had served with the Studies and Observation Group (SOG) in Vietnam, along with several who’d served with the 22nd SAS and been trained in CQB and BG tactics. SF Berlin would be followed by other units trained for the CT mission, including the short-lived 5th SF Group’s “Blue Light” program, then in 1978 by SF Operational Detachment Delta and in 1980 by the Navy’s SEAL Team Six. Many other nations launched similar programs during the early 1970s — Israel, Germany, and France, among them.

No matter the origin, it is important to note that CQB techniques have never been fixed in their presentation but are always adaptable to the situation and the weapons used. The key to CQB, therefore, is not the instruments used but the spirit behind them. This attitude is nowhere more eloquently described than in this British training guidance from the 1970s. It is reprinted here without change to its original form.

RESTRICTED

CLOSE QUARTER BATTLE (C.Q.B.)

The aim of CQB training is to guarantee success in killing. It is much more of a personal affair than ordinary combat, and it is just not good enough to temporarily put your opponent out of action so that he can live to fight another day. He must be definitively and quickly killed so that you can switch your whole attention onto the next target.

Besides obvious physical abilities, the CQB operator must be cool-headed and, above all, remorseless.

Opponents must never be given “gentlemanly” chances. He must be kicked whilst he is drown so that he stays down. This is imperative.

The pistol and submachine gun are the main weapons used by the CQB operator. These weapons are generally regarded by the ignorant as “dangerous” and “useless.” In the hands of a trained. CQB operator, these weapons are extremely lethal. However, for the CQB operator to maintain a high degree of professionalism, he must train continuously in an aggressive manner;

The end product of CQB training must be automatic and instantaneous killing.

The general coverage of CQB is under six headings:

a. Surprise – The operator must gain complete surprise over his opponents in all possible situations. This is achieved by good intelligence, planning, briefing, method of approach, choice of weapon for the job, choice of footwear, etc. If these principles are adhered to, they will result in the success of the operation and also ensure that the operator himself is never surprised.

b. Confidence – Successful CQB is largely a matter of confidence. Confidence in himself, the situation, and his weapon play a very big part in ensuring the success of an operator. The confident handling of his weapon makes lethal CQB shooting from almost any angle as easy as punching a drunk on the nose.

c. Concentration – Another abbreviation of close-quarter battles could well be CTK (Concentrate to Ki11). The operator shoots to kill, not hit. He must build up a clear, defined picture of every aspect of the job at hand. Nothing must distract him from his purpose of killing in a systematic fashion.

The mind does wander quite easily, but this must not be tolerated in CQB. It must be emphatically stressed upon from the moment the student starts his training. A wandering mind is usually detected in training by a fall-off, which results in and, of course, in the real thing by a vacancy for a new operator arising.

d. Speed – In CQB, contact is over in a matter of split seconds. Therefore, speed is vital, but it must be the correct type of speed. The mad. A wild, plan-less rush is not only foolish but, in most cases, catastrophic. The speed must be of a cool, unruffled, deliberate nature. Accuracy and success go naturally with this speed. The tempo of all CQB is “Careful Hurry.” This tempo must be adhered to throughout the training. Keenness and excitement are natural amongst students, but they develop at an incorrect speed. It must be stamped out from the word “Go.” The Battle-crouch, with its ensuing good, deft footwork, must be strictly adopted. An exited student will get himself into the oddest firing positions and so become off balance. The CQB Operator must never become flustered and stray from the “Careful Hurry.”

e. Teamwork – individual CQB operators in Special Forces are exceptional, and normal operations are carried out by small teams or patrols. Due to the close proximity and speed of the participants in CQB, the absolute essence of teamwork is of primary importance. Who goes where and when? Who kills whom and how? Synchronized timing, etc., must be spot on. A team going on an operation must be given all the time possible to study its target and plan its execution. They must rehearse time and time again, taking into account all the possibilities of target routine change. After initial CQB training, Students should be made to work in pairs, covering each other during tactical approach and withdrawal, etc. Afterward, add a third and fourth man, building up to patrol strength,

f. Offensive Attitude – In CQB, from the very start, the gloves are off. It is a simple matter of “his life, or yours.” Squeamishness, pity, remorse, or mistakes are fatal. Nothing should be done in self-defense. All actions must be of an extremely offensive nature. Operators should develop hatred and contempt for the opposition but never underestimate him.

Students should be edged into this determined and offensive spirit from the commencement of training.

RESTRICTED

About the Author

Present at the beginning of U.S. Army Special Forces’ involvement in CT operations, James Stejskal was trained in and later taught “CQB” techniques during his military service. He has written both the narrative history Special Forces Berlin and a series of Cold War espionage / special forces novels called “The Snake Eater Chronicles.” His novels, Appointment in Tehran and Direct Legacy, describe what it was like to go through SF Berlin’s and SAS CQB training in the 1970s and 1980s.

COMMENTS