SOFREP: Did you have a good support group of other African American Marines to be there for each other along the way?

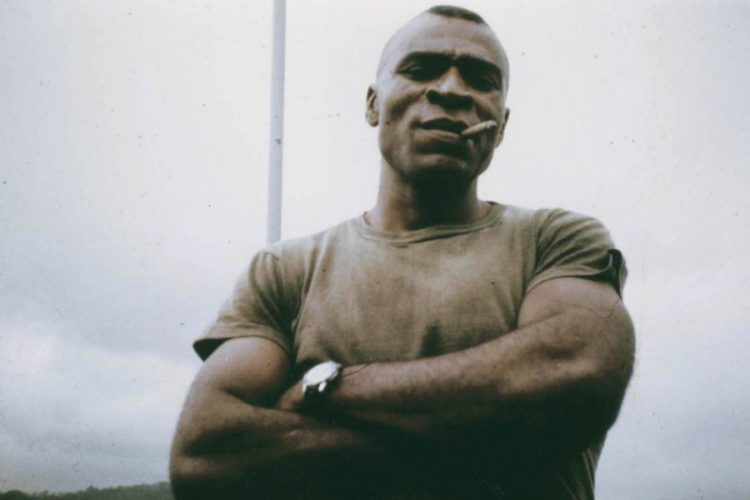

In my line of work, because there were not a lot of African Americans in special operations, I started off in force reconnaissance and the old Pathfinders group.

And it was a requirement for strong swimmers. You had to go to the SCUBA program. A lot of those guys, if you look at from a historical point of view, of course, I was born on a farm and we picked cotton and crop tobacco and those types of things. But when I moved to Baltimore, I lived in a city and a lot of the places like the neighborhoods I lived in didn’t have swimming pools and it was against the law to go into the white swimming pools.

So, you didn’t really get the basics. You didn’t learn to swim. I had to learn to swim by imitating Tarzan. Going to old creeks and jumping in there and swimming and getting the basics. And then of course, when I got into the Marine Corps, I was able to go to swimming pools and learn those types of things.

But a lot of African Americans did not have that opportunity or, maybe, not that motivation. So, I didn’t have a collective group of African Americans in special operations. If you look at the SEALs and the Delta guys, you never found a lot of those guys in special operations. But still collectively, because we were a lot of us African Americans from the South, and we supported each other, but I got a lot of support from the whole community.

I was really never spat upon by my other contemporaries. A lot of it is the way you conduct yourself. You know, I got along well with my white contemporaries, a lot of us were from the South, and I got along well with the Army, the Navy. A lot of it is on you. If you conduct yourself properly, most people would accept you. There were a lot of Christian-hearted young men and women that I met, and we believed in that. We believed in fairness, we believed in justice, we believed in Christianity. So that was our connection. We had many Bible studies together.

That was our connection. Didn’t always work, there were some issues of course, but to answer your first question: Did I have a support group among young African Americans? Not really because they weren’t there and [in] the groups that I was in, but at the same time, didn’t make much difference because I was a Marine.

My other contemporaries were Marines. We had Jewish guys, we had Latinos. So, you make friends where you can. We often went to the same church, so it was okay. And I think I can tell that story to young men and women today and they’ll find a little bit more righteousness because we are more attentive to it today. A lot of the old days have gone, and we are more accepted — at least I’ve been accepted.

SOFREP: Has there ever been a point where your faith in the Marine Corps as an institution has ever wavered?

Well, I think so. Hard to say at this point in time, you loved the Marine Corps, but there were times in battle and after the battles. There are times when I momentarily lost my faith as a Marine during the war. I saw so much destruction and so much death, and it weighed heavily on me as a commander. And I’ve got young troops that I trained and took to war, and I did the best I could, but I didn’t bring them all home and I blame myself for that.

There were times when the weapons didn’t work, and we didn’t always get the supplies we needed. Some of the leadership was bad. But those are things that happen in all wars, but then again, I took it personally and I challenged the institution to do better for our troops.

And I did as much as I could to make sure they were well fed, well armed, well equipped, but sometimes that didn’t come through the supply line. And I blame the institution for that. A lot of it was politics. There’s no easy way to explain losing your faith in your institution, but I’ve never lost my faith in God. I questioned momentarily. And even looking back now, I understand why we didn’t get everything we needed. And, you know, we lost 55,000 young men and women in Vietnam. Certainly, looking back, we questioned why those young men had to die for a country that most people before that war could not even pronounce [its] name [and] didn’t know where it was.

So, you can question your institution. You can question the politics of it. But when you’re an American you have faith in your country.

SOFREP: Is there one thing that you wish that you could convince the Marine Corps leaders of today to correct? Is there anything that still has not been fixed since the time you were on active duty?

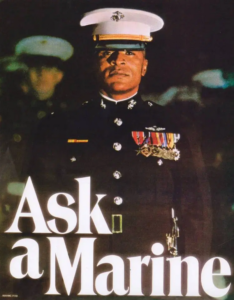

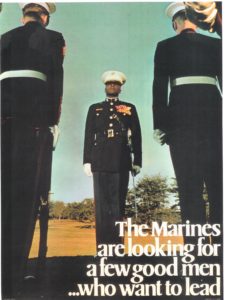

Well, I was actually talking about this earlier today. But recently 10 Marine Colonels were selected for Brigadier General. And on that list of 10 colonels, there was not one African American. There was one female on that list. But in order for us to attract young, bright servicemen and women into the officer corps, we have to show that they can reach to the top. But the example we set right now — and I’ll have to deal with this later on in another setting — but when you have 10 colonels and not one African American or Latino or one minority, it’s hard to encourage young men and women to come in the Marine Corps, our smallest service, and to say, well, if I do a good job, I can rise to the top, because there are no examples that will show that. We only have six African American generals in the Marine Corps as opposed to dozens of them in other branches. So, it’s hard for me, when a young man comes up to me [and] says, “I’m thinking about the Marine Corps.” It’s hard for me to say, well, yeah, if you work hard, you can get to the top, but there are no examples of that.

And I think that’s what I would tell to the leadership today, you know, and it’s not all about racism or whether African Americans get picked or not. But it is. There’s a large percentage of this country, African Americans; that’s 400 years of slavery and mistreatment. We have to get beyond that. We have to be aware. Awareness is a big thing.

Now, a lot of people come to me for advice on Black Lives Matter, and this and that and [ask me]: “Would I kneel before the flag?” I said, no, I won’t. I’m not going to kneel in front of the American flag. Now, of course, there are a lot out there as well. They have their opinions and they have a right to it because I shed a lot of blood for this country. They have the right to make their own choice. I don’t have that right anymore. I saw too many coffins draped with the American flag. I’ve seen too many American flags in battle zones around the world.

I believe in this country. I understand and accept the fact that we’re not perfect, but well, Jim Capers, who was born in the South and I [were] given to a white family because I was sick. My family couldn’t take care of me, and they saved my life. These are things that I appreciate. I wasn’t a black child to that family; I was a human being. This was in the South. Now, there were other things, of course, that [weren’t] perfect in the South. We know about slavery and those types of things. But since I matured in the Marine Corps and my life was saved [by] a young man from Alabama. So, I [had] had to get by the totality of the racial thing.

I have to look at the reality of what was done to me and for me, and I made a decision that I love my flag. I love my country. I accept the things that [are] not right, but I cannot stand before this flag and take a knee to demonstrate the inequities. I know about these inequities. I’ve lived through [them]. I sat in the back of the bus, you know, I have.

I couldn’t eat in restaurants. I couldn’t get a drink of water in a public water fountain. So, I suffered. My father went to the chain gang for a crime he didn’t commit. I have picked cotton and [cropped] tobacco. I walked behind a mule, you know, so these are things that I’ve done. But out of all of that, somebody that didn’t look like me saved my life.

When I was dying and bleeding to death, a Navy Corpsman from Alabama came over and gave me morphine and helped save my life. So, when you look at the totality of this, he was from the South, I was from the South. And now we talk about that Confederate flag. I kind of grew up under the Confederate flag. I was never offended by it because I didn’t really know a lot of it, but once you’re educated and you know, that too many African Americans did a lot of the hard labor, practically built this country for no wages and could not be married, could not own property, could not be educated.

These are the things that were denied to my ancestors. And of course, until Martin Luther King [came] along and Civil rights laws were passed, we didn’t have a civil rights law when I went to war as a young man in my teens, but as we become older and now we see a lot of things that we didn’t see before and we’re correcting those things.

Now, there are a lot of options, you know. We could let it stand the way it is, or we can still be that bright beacon on the hill that attracts more people and feeds more people, cares for more people. We need to continue to do that. But at the same time, we need to recognize that this country was built on promise.

And some [of it] was built on hate and cruelty. But we have gotten by most of that, [yet] we still have got a way to go. And so, my thought is that I fought for that flag. I respect those who don’t want to stand for it or sing God bless America. I can’t do that. I can’t do that. And will not do that. There are others when you see [them] on television, athletes who are making millions of dollars, of course, they have the option. We’ve given that right to do that. And my heart, I will always stand because I love my flag. I love my country. Some of the things that occurred, I’m not happy with, but we can do better. We will do better. We will do better.

COMMENTS