A few years ago my right leg started bothering me. I love to walk but I couldn’t make it a block without experiencing searing pain in my right leg. I was scared to go to the VA so I scheduled an appointment with the Ortho department at NYU while I was in New York and paid out of pocket.

After the x-ray, the doctor said, “Have you ever had a hard impact on your right leg?”

I knew exactly what she was talking about.

My only hard parachute landing, at night. Damn, did that one hurt…

On a cloudy moonless night in Yuma, Arizona I was parachute training and lost sight of the ground at about 1,000 feet as I was turning my base leg into the wind to land. I couldn’t see the ground and I had a full combat load. I pulled the cord to release my ruck sack to drop below me, checked my altimeter, “300 feet”, and still no sight of the ground. Not a comfortable feeling but I knew the procedure. Pull my risers evenly to 50 percent brakes, feet and knees together and take it like a man for what we call a “PLF.”

Just when I was convinced I wasn’t slowing down enough, BOOM! I hit the deck.

I thought my right leg was broken for sure.

Standing up, I walked enough to know it wasn’t broken and then lied down to have a few minutes of alone time with the kind of pain that really makes you feel alive. Fifteen minutes later I got up and limped to the truck with my gear.

The army medic I saw gave me some Motrin (no medical record entry) and I limped (no pun) through the remaining training jumps with landings so precise the Blue Angels would have complimented me on my form.

A few weeks later and I was back at full strength with no knowledge this one would pay me a visit years later at the NYU clinic.

“You chipped your hip socket with that landing. I’ll get you to a hip specialist who can rehab and hopefully rewind a few years so you don’t have to have surgery,” the doctor said.

After months of expensive private rehab, I was feeling normal and not limping as much. Losing your mobility is really hard to take so I was glad to feel kinda back to normal. Then a friend recommended a specialist in California who did stem cell injections. It was really expensive but how much is our health worth? So I spent the money. It worked and got me to a decent place but like my back, I now do extensive rehab on my own to keep muscle strength around the injury.

The VA Marathon Begins

Then I went to file a VA claim to document the injury because it had occurred on active duty. I submitted a personal letter describing the incident, three doctor letters supporting my claim, MRIs, and my x-ray.

After a year of waiting the VA sent me a letter saying my claim was denied. “Not enough supporting evidence,” it said.

After hours of dropped calls and hold times, I reached a representative that said they made appointments for me but I never showed. I apparently hadn’t gotten the notice. They had booked me two back-to-back appointments in locations that were hours apart. It would have been impossible for me to even make the appointments unless the VA was hiding a Star Trek teleport machine they secretly used to beam me from one appointment to the next.

They had scheduled appointments for me, without my knowledge, consent, or input. It was as if I were living on the streets, beer can in a paper bag, with nothing to live for but my VA appointment.

All I could think about was the veterans that really needed help and would be too frustrated to press on and just give up.

And who could blame them?

For now, my issue is fixed. I’ll hopefully get my exams and VA rating for my right hip but the entire process has taken close to four years (three years if we grant a pass for COVID).

Some Potentially Concerning Data

Any veteran who needs immediate assistance, especially with thoughts of suicide, will be completely let down by the current system.

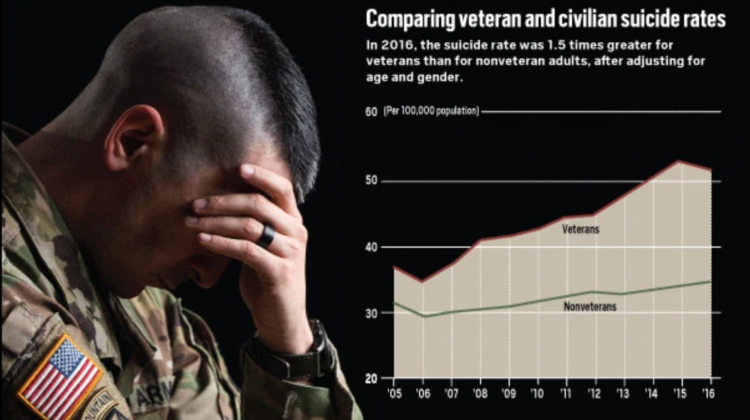

America is failing to take care of the thousands of transitioning veterans who fought in Afghanistan, Iraq, Africa, and elsewhere in support of the Global War on Terror. This is shameful. I feel ashamed that our country is doing this.

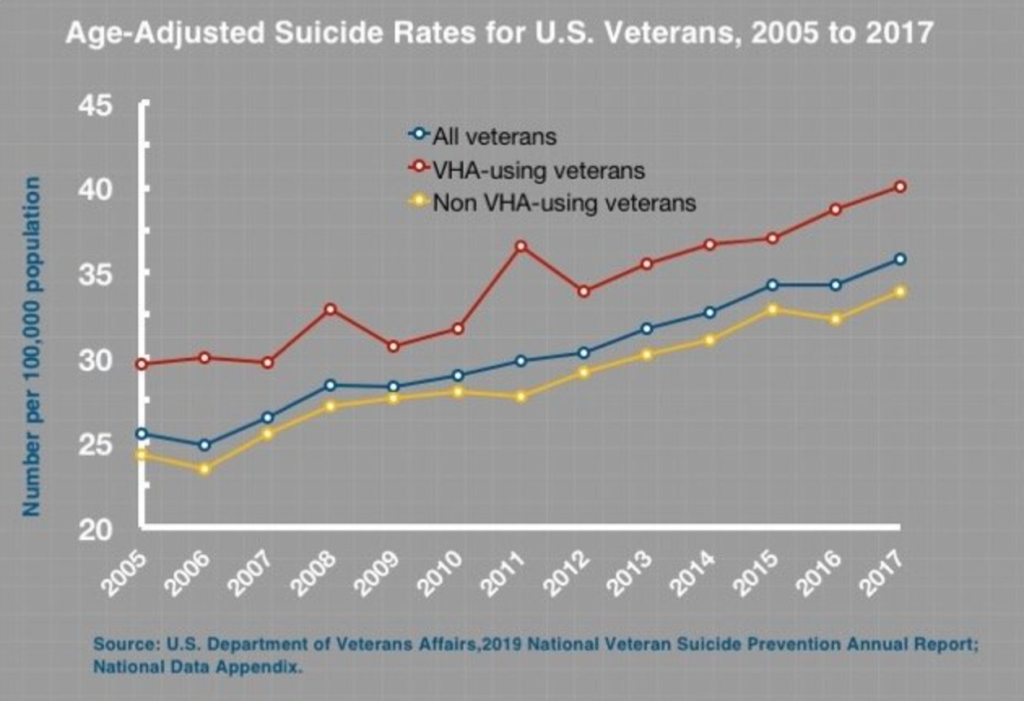

The chart above shows that the veterans who enroll in the VA system are more likely to commit suicide than those who don’t enroll. Think about that for a moment and let it sink in. Although the data may reflect that the veterans who enroll in the VA are the ones with the more pronounced problems in the first place, still, the graph should give us pause.

*If you have a VA experience, good or bad, SOFREP wants to hear from you. If you are a VA worker and have a story to share, please use our contact form and write in. All will be treated as confidential.

COMMENTS