The Army and Hendrix were never going to work out long-term. But something happened in those barracks that mattered more than any evaluation report.

The Woodshed

In music, we call it “shedding.” You lock yourself in a room and play the same lick, the same scale, the same phrase… over and over, and then over, until your fingers bleed and your brain rewires. It’s brutal. It’s boring. It’s work. But it’s necessary for those who want it badly enough. Every serious musician knows about woodshedding. You don’t skip it. You just do it.

Jump school operates on the same principle. Repetition until the fear doesn’t disappear… it just stops running the show. You jump anyway. You do the thing every instinct tells you not to do, again and again, until your body trusts what your mind has learned.

Hendrix was a terrible soldier by almost every measurable standard. But he understood the woodshed.

Soon after, his father shipped him a red Silvertone Danelectro guitar from Seattle… the one Jimi had hand-painted with the name “Betty Jean.” From that moment on, every spare second went into that instrument. Fellow soldiers hid the guitar from him just to get some peace, as woodshedding actually sounds like shit. It isn’t a performance, it’s learning. Didn’t matter. He’d find it. He’d play.

One night, a serviceman named Billy Cox (legendary) was walking past a club on base when he heard sounds coming from inside that stopped him cold. He later described it as “John Lee Hooker and Beethoven” happening at the same time. He grabbed a bass, introduced himself, and the two started jamming. They’d play together for years.

That wasn’t natural talent people were hearing. That was a man who had committed to the woodshed like his life depended on it.

The Stage is the Drop Zone

Here’s what civilians don’t always understand about performing live: Whether it’s a mission or a gig, the fear never fully goes away.

Hendrix jumped out of airplanes. Earned the patch. Did the hard thing. And yet, just as I was, early in his music career, he was painfully shy on stage. He’d turn his back on the audience. Play sideways. Couldn’t look people in the eye while performing.

But he did it anyway. Same as the jump.

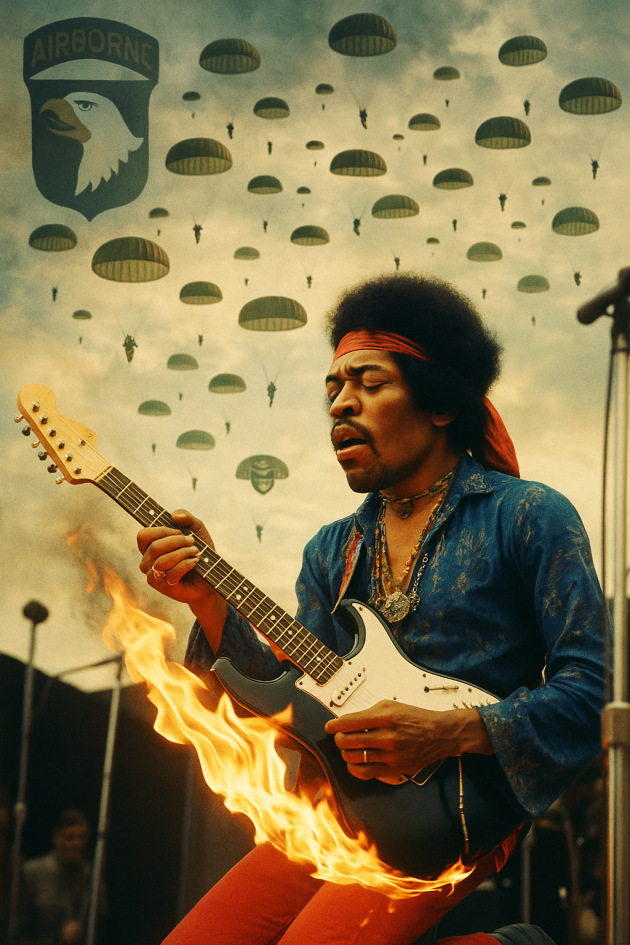

There’s footage of him at Monterey Pop in 1967, five years removed from Fort Campbell, setting his guitar on fire. Destroying it. Full spectacle. That wasn’t ego. That was a man who had learned what happens when you commit all the way through. No half measures. You don’t dangle your feet out the door of the plane and think about it. You f-ing go.

Humility is a Superpower

But the part that gets so often overlooked in the Hendrix legend? He never forgot he was a soldier.

On the Dick Cavett Show, he talked about his paratrooper training with quiet pride. At Woodstock, when he played that searing, distorted version of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” people assumed it was a protest. Maybe it was. But when Cavett asked him about it directly, Hendrix just said, “I thought it was beautiful”…And it damn sure was.

On New Year’s Eve 1969, at the Fillmore East, he dedicated “Machine Gun” to the soldiers fighting in Vietnam. Not against them. To them.

He was complicated. He contained multitudes. And he never lost the humility that made people actually want to listen to him. The best operators I’ve ever known carry themselves the same way… no chest-puffing, no posturing. They know what they don’t know. They stay students. I call it quiet badassery.

Hendrix died at 27. Choked in his sleep. All that potential… gone.

But what stayed was this: A paratrooper from Seattle who couldn’t shoot straight and couldn’t follow orders changed the way humans understand what a guitar can do. He shedded in the barracks. Jumped out of planes. Played through fear. And never lost the humility that real mastery requires.

Not a bad legacy for a guy who only joined up to stay out of jail.

—

If you liked this story (and I know you did), please check out T’s popular book, “Life in the Fishbowl.” In it, he documents his time as a deep undercover cop in Houston, where he took down 51 of the nation’s most notorious Crips.

He donates all profits to charities that mentor children of incarcerated parents.

—

Tegan Broadwater is an entrepreneur, author, musician, former undercover officer, podcast host, and positive change-maker.

Learn more about his latest projects at TeganBroadwater.com

Tegan’s Music (Artist name: Tee Cad)

Spotify: https://open.spotify.com/artist/5LSl3h5TWN1n4ER7b7lYTn?si=o7XaRWEeTPabfddLEZRonA

iTunes: https://music.apple.com/us/artist/tee-cad/1510253180

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/@teecad/releases

—

** Editor’s Note: Thinking about subscribing to SOFREP? You can support Veteran Journalism & do it now for only $1 for your first year. Pull the trigger on this amazing offer HERE. – GDM

COMMENTS