A rescue helicopter tried and failed. The situation was closing fast.

Fisher did not wait for orders.

He brought his own A-1E down under intense fire and landed on the damaged strip. Nineteen bullets tore into his aircraft as he taxied more than 2,000 feet through wreckage and craters. He reached Myers’ disabled plane, loaded his wounded wingman aboard, and turned back toward the end of the runway.

Taking off under direct fire, Fisher lifted the damaged Skyraider into the air and carried Myers to safety.

It was not dramatic in the way movies portray heroism. It was precise, violent, and unforgiving.

And it saved a life.

Recognition and the Medal

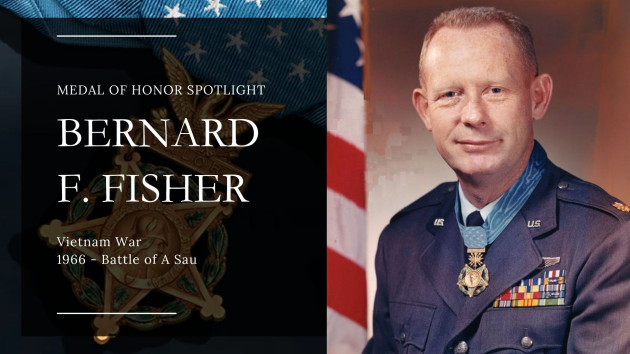

On January 19, 1967, then-US President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Bernard F. Fisher with the Medal of Honor at the White House. He became the first Air Force recipient of the Medal of Honor for actions in Vietnam.

The citation spoke of conspicuous gallantry. The moment itself spoke of something simpler. A pilot who refused to leave another pilot behind. Here’s an excerpt from his Medal of Honor citation:

“…Although aware of the extreme danger and likely failure of such an attempt, he elected to continue. Directing his own air cover, he landed his aircraft and taxied almost the full length of the runway, which was littered with battle debris and parts of an exploded aircraft […] In the face of the withering ground fire, he applied power and gained enough speed to lift off at the overrun of the airstrip…”

After the War

Fisher returned to Air Defense Command, serving with the 496th Fighter Interceptor Squadron at Hahn Air Base in West Germany and later with the 525th at Bitburg Air Base. In 1969, he became operations officer for the 87th Fighter Interceptor Squadron in Minnesota.

His final assignment was in Boise, Idaho, where he served as Senior Air Force Advisor for the 25th Air Division. He retired as a colonel on June 30, 1974.

Retirement did not quiet him. Fisher wrote Beyond the Wildest Dreams in 1992 and spoke often at military academies and Air Force events. He focused on responsibility, judgment, and leadership. He did not chase attention. He let the example speak.

A Quiet Legacy

Bernard F. Fisher died on August 7, 2014, in Boise, Idaho, at age 87, from complications related to dementia. He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery with full honors.

He is remembered as the first living Air Force Medal of Honor recipient from Vietnam. More importantly, he is remembered as a man who landed where landing meant near-certain destruction because another pilot was still alive on the ground.

Courage does not always roar. Sometimes it sounds like an engine coming in low, steady, and unafraid.

Fisher made his choice. The Air Force remembered. And so do we.

COMMENTS