Beyond this broad plan, the Americans did not think the project through. The island was about the size of an average American county, and the farmers and fishermen could not support many thousands of prisoners. Worse, thousands of North Korean refugees who were evacuated from Hungnam would also be dumped on the island. It was a certainty that some of them were North Korean agents. Eighth Army barely noticed.

Speaking of which, Eighth Army was still the command authority for the prisoners. This was the worst kind of administrative set-up possible. Eighth Army was fighting a major war. American HQ in Tokyo should have taken over, but at first they were caught up in events in Korea and MacArthur’s firing. After that, they didn’t care much.

Army Engineers were deployed to Koje-do. They were told to get a camp up quick and dirty. Compounds that were supposed to hold between 500 and 1200 POWs each would soon be crammed with five times that number. The island could not possibly supply all the food needed, so it was mainly purchased in Japan.

Nobody was expecting any real trouble, so the compounds were only separated from each other by a little barbed wire. This meant that information could easily move back and forth between compounds, and even prisoners.

ALL of the guard positions were outside the compounds, outside the border fence line. This meant that there was absolutely no control over what went on in the prisoner areas.

Meanwhile, civilians could and did walk right up to the fence and throw messages over the wire to the prisoners, who often threw messages back. Sometimes items were smuggled in over the wire. The drivers of the “honey bucket” wagons often carried messages and contraband. They reeked so much of human excrement that none of the prison staff, especially the Americans, wanted to go anywhere near them.

Ultimately, there would be about 170,000 prisoners behind the wire. No idea who the players were without a scorecard, and there were no scorecards.

Seems that 21,000 were Chicom soldiers. Some 28,000 were North and South Korean civilians, arrested in giant dragnets by the South Korean government. Most civilians would be cleared and released over the next fifteen months.

Thousands of NKPA (North Korean Peoples Army) prisoners were South Korean citizens who had been drafted at gunpoint by the North Korean Army during its invasion of the South. Months would be needed to isolate, clear, and release those individuals. More than 3000 of the POWs were under 17.

The North Korean soldiers themselves fell into three main groups. Those who hoped to eventually be released into the South, those who wanted to go back North, and the real “father rapers,” the absolute drooling fanatics. Some 6500 of the worst of the worst of these were placed in compound #76.

About the three leading lights of this group: Senior Colonel Lee Hak-Ku, NKPA. He was the highest ranking North Korean officer to wind up in UN hands. Senior Colonel Hong Chol was a malignant sort of character, most likely the political officer, bloodthirsty. And the oddest character, possibly with the most authority, was Pak Sang-hyon.

Pak Sang-hyon seems to have fled Korea during the Japanese occupation. He became a Soviet Citizen and was drafted into the Soviet Army. He may or may not have been a civilian when he was in Koje-Do, or a North Korean Colonel, or a Soviet Captain; the record is not clear. Most likely he surrendered deliberately to get into the camp.

It did not help that many of the guards who dealt with the prisoners were South Korean soldiers. Korean Communists and Korean Anti-Communists loathed each other with an almost hysterical fervor. Some of the guards were too quick with truncheons and firearms. It didn’t help that when the POWs arrived they were given better rations than their Korean guards.

Other South Korean guards were at the camp because they were screw-ups. Some were lazy, others were easy to bribe. One investigation turned up escape maps, civilian clothes, medical supplies and weapons, all provided by bribed guards.

It eventually became clear to anybody who cared to look that the North Korean fanatics ran the show inside the Korean compounds. Peoples Courts were held, and bodies would appear in the latrine areas or found jamming up the sewage pipes.

In the U.S. and U.K. during WWII, some Nazi fanatics tried the same sort of thing in Allied POW camps, but the Allies rooted them out, tried and hanged them. Unfortunately, the Truman administration specifically forbade such proceedings for North Korean prisoners. So no investigations were held, and the fanatics continued to get away with murder.

It became clear after a period of time that some of the Korean nurses in the hospital were Communist agents. They not only smuggled information and contraband, but quietly murdered some POW patients known to oppose the fanatics.

American soldiers were also sent to Koje-do as guards. Too often they were the of the worst quality, and were sent to the island to get rid of them.

The American General commanding this lash-up had enough sense early on to ask for more barbed wire, material and engineers to expand the camp and rearrange it so as to be easier to control what went on. He was told that nobody was going to authorize any of that, and just get by with what he had.

However, political pressure from the International Red Cross and others made sure that there were always funds for anything that the prisoners wanted. Not just the usual recreation and hobby items, but paint, sheeting for banners (political slogans), a “blacksmith” shop with plenty of sheet metal, and countless other items.

There was a shortage of combat fatigues since so many had been sold as surplus at the end of WWII. So many of the POWs were wearing officers’ “pinks and greens.”

To complicate all of this, the peace talks at Panmunjom hit a snag. Many of the Chinese POWs did not want to return to the PRC, but instead wanted to go to Nationalist China. A great many of the North Korean soldiers wanted to be discharged in the South. This was a massive propaganda black eye for the Communists.

So orders filtered into compound 76 that they were to prevent screening of Communist prisoners at all costs. If all else failed, they were to stage a massive breakout that would cause most of the prisoners to be killed by U.N. forces and give the Communists a major propaganda victory.

The camp began to heat up. On February 18, 1952 there was an incident where a battalion of the 27th Infantry rescued a South Korean guard. When the dust cleared, out of some 1500 rioters, 75 North Korean POWs were killed and 139 wounded. One G.I. was killed and 22 wounded.

On March 13, shots were fired to quell an incident. 22 NKPA were killed and 26 wounded. On April 10, a number of North Korean POWs attempted to rush the gate, but an American officer stopped them with a jeep-mounted machine gun, killing 3 and wounding 60.

The North Koreans and even the Chinese were producing flags and banners, holding demonstrations and in general raising hell. A South Korean soldier somehow “vanished” into one of the North Korean demonstrations. More bodies began to appear.

The International Red Cross delegation was headed up by a total pea-wit. He harangued the American commander about many bad conditions, including North Korean commanders not allowing food to men that they did not like or trust. But at the same time he made it absolutely clear that he would not support even the slightest use of force to remedy the situation. Amazing that he didn’t wind up being found one morning clogging the sewer line,

Then on May 7, General Dodd obligingly walked into a kidnapping. The Eighth Army and Tokyo suddenly decided that the camp now warranted their attention.

Brigadier General Charles Colson was directed to handle the matter. Meanwhile, compound 76 had placed General Dodd “on trial,” and Colson was authorized to use whatever force that he might deem appropriate.

Colson had Dodd free in no time flat. He simply signed a statement prepared by the North Koreans that the U.N. would no longer “starve and torture Korean prisoners and attempt to force them to defect.” It was immediately published around the world.

Eighth Army and Tokyo stunned. They had expected an armed assault (nice if they could get Dodd out alive, but he really should have known better than to stick his neck into the noose). Instead, the U.S. and the U.N. got a massive propaganda black eye, with even friendly countries asking just how “inhumane” Allied forces were at Koje-do. Tokyo and Washington immediately disavowed it, but the damage was done.

Colson and Dodd were demoted to full Colonel and sent back to the States to be retired. Meanwhile, armed North Korean fanatics controlled the camp at Koje-do.

Eighth Army was relieved of responsibility for Koje-do and was allowed to go back to fighting the war. Tokyo needed somebody tough, smart, and expendable if things went South. The call went out for Brigadier General Haydon “Bull” Boatner, assistant division commander of the 2nd Division in Korea, who just happened to be on leave in Tokyo.

BIO: Brigadier General Haydon “Bull” Boatner

- Commissioned in the Infantry from West Point in 1924.

- Graduated from Command and General Staff School in 1939.

- Commanding Officer of the forward echelon in Burma 1942.

- Brigadier General in November 1942.

- Chief of Staff of the Chinese Army in Burma 1942-1943.

- Commanding General of combat troops in northwest Burma 1943-1944.

- Chief of Staff of Chinese Combat Command 1944-1945.

Boatner had graduated at the top of his class at West Point. Arriving at the CBI (China-Burma-India Theater) in WWII, he was one of the first of his class to be promoted to Brigadier General. And there his career, through no fault of his own, stalled.

Not much room for promotion in the CBI, and his boss, “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell, made a lot of enemies in Washington, especially by attacking Chiang Kai Shek. When the Korean War broke out, Boatner was Commandant of Cadets at Texas A&M.

Arriving in Korea, he was unlikely to be promoted. MacArthur supported his own SW Pacific “Mafia” from WWII, and MacArthur’s replacements favored their comrades from the ETO. Boatner should have had a division. When his division commander moved on, he was not promoted. His Corps Commander had been junior to him in Burma, but transferred to the ETO.

When he arrived in Korea, he found that the 2nd Division was sending men onto hills with bunkers without enough flamethrowers and few men trained to use the ones that they had. He personally remedied both situations and 2nd Division casualties went down significantly.

Boatner hardly looked like a General. He looked more like a friendly guy who owned a chain of tire stores, or maybe a professor. He was flabby and unlikely to ever be promoted. But unknown to just about everybody, he was one of the finest officers the Republic ever produced.

Boatner was nobody’s fool. He demanded absolute authority, unlimited funds, and the right to call on any military force in Korea or Japan. A very desperate Tokyo gave him all that.

He wanted the civilians on Koje-do moved far away from the camp. Tokyo said that they had no authority. Boatner took care of that almost immediately. When asked about it by a journalist, he said only that Tokyo had the authority, putting them in the hot seat. The civilians were moved.

Boatner showed up on Koje-do and was stunned to learn that many of the American officers there had no clue. They were organizing a cocktail party for him, and trying to work out what uniform his staff would wear. “You don’t want your staff wearing the same uniform as the guards…”

Boatner had picked up his nickname “Bull” at A&M, He came down on all of the American officers like a ton of bricks. An armed enemy controlled the inside of the camp and every officer and man in Boatner’s command had better start acting accordingly.

He ordered that all Americans would carry arms at all times. “General, you don’t want to do that, somebody will have an accidental discharge…” Most of Boatner’s reply consisted of words unlikely to be found in the Bible.

Boatner had 400 of the worst American guards shipped off the island and replaced immediately by quality soldiers. This improved the morale of the better troops who remained.

He had a Combat Engineer battalion immediately deployed to the island. He went to check it out, and found them painting rocks and rain barrels around their quarters and setting up a PX of their own. He had a few choice words with the Lt. Colonel in command. Boatner told him that this was an emergency and that priority construction would take place 24 hours a day. Once their ideas had been woken up, the engineers hit the ground running.

Various U.N. nations with troops in Korea had seen fit to criticize the camp and its situation, so he got them involved, very much against their will. He had a company of Canadian troops, one of British, one Turk, a battalion from the Netherlands, and a few Greeks deployed to the island.

The briefing was something that they did not expect. They were told that if prisoners attempted to scale the fences and other prisoners attempted to stop them, that they were to shoot the ones attempting to stop them. The POWs hitting the wire likely trying to escape Communist fanatics.

The British government (which was not pleased at fighting China) objected. The Canadians made noise too, but largely just for domestic consumption. In any event, the orders stood. The Allied contingents did good work in some of the less threatening sectors.

If it came down to heavy killing, Boatner had the excellent 23rd Infantry Regiment. If a massive breakout was attempted, they would crush it. Also, 20 Patton tanks (five of them equipped with flamethrowers) and Quad 50s.

But for more limited and controlled use of force, for killing with cold steel if it came down to it, he demanded and got two battalions of the 187th Airborne from Japan.

The Red Cross and reporters had been removed when Dodd was kidnapped. Boatner not only allowed them back, but had Tokyo order a large number of accredited correspondents to the island. This was going to be done in the open.

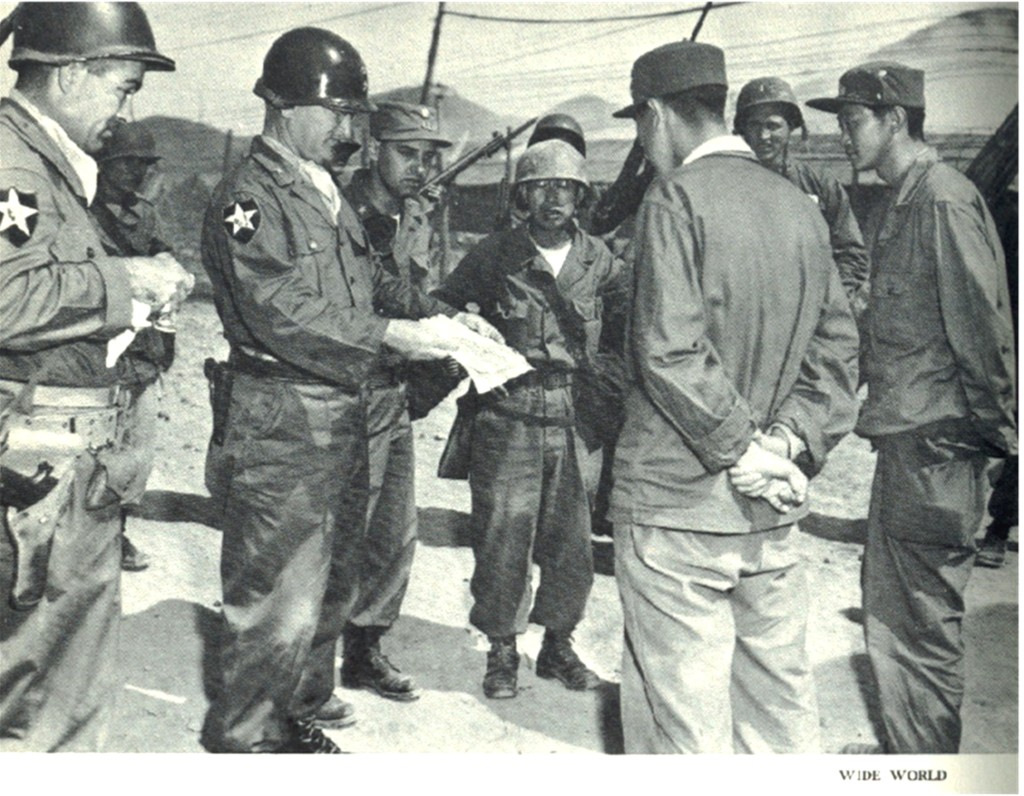

Boatner was advised that the Chinese compounds were acting up again, with banners, chants and protests. He decided to deal with the Chinese immediately. He had the senior Chinese officers brought to his office.

The officers were loyal to China, but not Communist fanatics. They saw no reason not to act up when everybody else doing it.

Reporting to his office, they indicated that a Chinese POW had been killed by an American guard. They wanted the entire Chinese group to attend the funeral, and had many other outrageous demands, including a bunch of toilet paper and mecurachrome,

The translator finished the translation. Boatner waved him out of his office. He looked at the Chinese officers and said in perfectly accented Mandarin, words that loosely translated meant, “What kind of bull is this?” The Chinese were shocked. He not only understood them, but his Mandarin was flawless, almost unheard of for a foreigner.

Boatner had spent a decade in China before the war. He not only learned the language, but obtained a Master’s Degree in Mandarin. He had commanded American-trained Chinese forces in Burma.

He told the officers that he had served with Stillwell (very well thought of in China, even during the Korean War). He named a number of well-respected Chinese generals who were personal friends of his.

The Chinese officers fell back and regrouped. They might have viewed previous camp commanders as weak and foolish, but Boatner was neither. He was obviously an “old China hand” and not to be taken lightly.

He told them that a small delegation could attend the funeral, and to enable them to save face, told them that they could have the toilet paper and mecurachrome, which could be used to make small flowers for the funeral.

He then courteously said to let him know if there was anything requiring his attention in the future. He told them that he might have to do something “just awful” to the North Koreans, but that he would guarantee the safety of the Chinese from all parties if they behaved as proper soldier POWs.

They left his office. The Chinese stopped demonstrating. No matter what Peking thought about the North Koreans, the Chinese officers loathed the more fanatic examples. They would be quite content to sit back and observe what something “just awful” might turn out to be.

Now the main task was to break the camp down into much smaller compounds, isolated from each other. No more than 500 men per compound. But compound 76 would fight to the bitter end to prevent this from happening to them.

A compound next to 76 was cleared. The paratroopers and tanks and flamethrowers then ran a “dress rehearsal” in the empty compound to show what 76 could expect.

For thirty days the engineers worked day and night to prepare alternate compounds. Boatner knew in his bones that there was a massive breakout planned, He could stop them from overruning his HQ and murdering staff and nurses, but the body count would enrage much of the world and damage the U.N. position at Panmunjom.

The day before 76 was to be cleared, Boatner had the North Korean senior officers advised of exactly what would happen, and how nobody would be injured if they followed orders. He then had the same information broadcast on loudspeakers to all the residents of the compound, not trusting their commanders. Other compounds were briefed and promised safety if they remained calm.

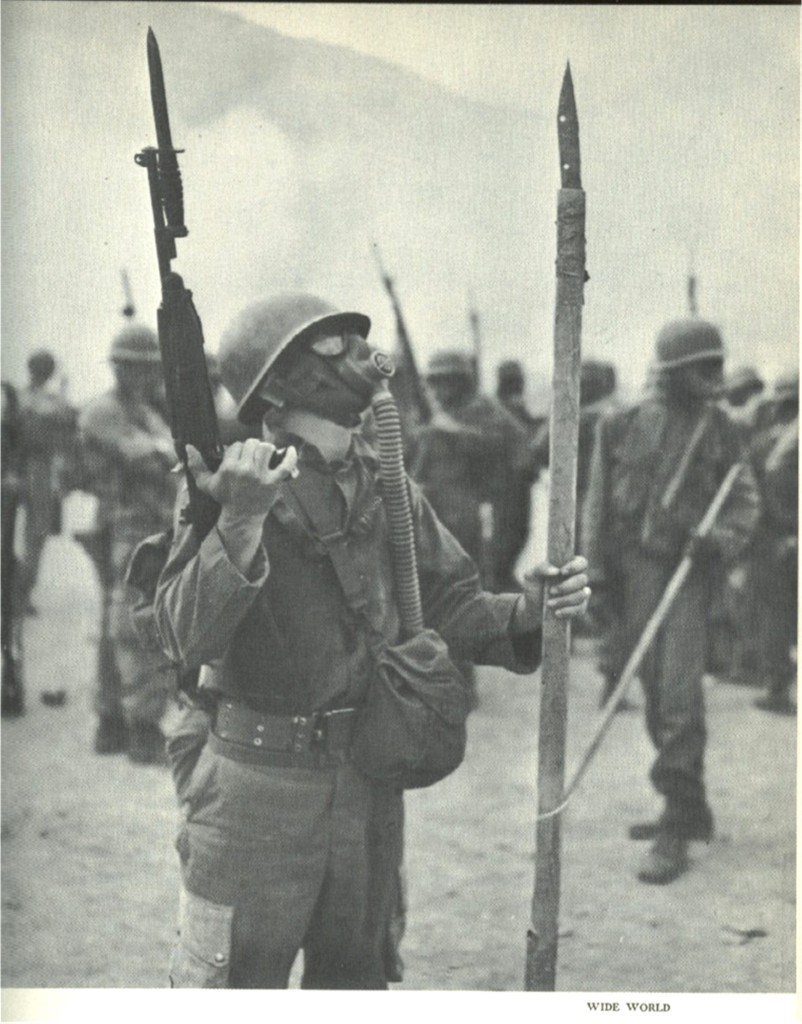

The morning of the move arrived. The tough paratroopers were wearing gas masks and had fixed bayonets. Except for a few designated snipers, none had a round in the chamber. Their orders were only to fire on specific orders from one of their officers, but they were told that, while they were almost certainly going to have to do some killing, it would be with cold steel. Any North Korean attempting to use a weapon was to be dispatched immediately.

The paratroopers knew what to expect. Compound 76 had many weapons, real and “bluff.” They caught glimpses of a “machine gun” that was only a mock-up, but also many weapons that were the real deal.

The “blacksmith” shop had been turning out spears and nasty looking “flails” made with barbed wire. Back when the prisoners could order just about anything, they had requested gasoline on some pretext, along with nail studded “firewood,” so there would be Molatov cocktails deployed against the Americans.

The loudspeakers issued a final warning in Korean. A few North Koreans tried to flee towards the Americans but were stabbed in the back. The paratroopers steeled themselves for what had to happen next.

They had the outer wire dragged off by armor. They then entered partway, accompanied by a tank platoon.

Tear gas, slow advance of troops and armor. Most of 76’s occupants fell back, but a couple of hundred set fire to their buildings and then attacked. The paratroopers had no qualms about crushing them.

Corporal John Sadler died of spear wounds. Thirteen other Americans were wounded. Thirty-one POWS died (half by their own troops) and 131 were wounded.

Boatner had kept the killing to an absolute minimum. Some of the media would squawk, but nothing like what the stories would have been had he been forced to deal with a mass breakout.

The Red Cross and Third World reporters (and, of course, the Communists at Panmunjom) raised a stink, but the body count was amazingly low, and besides, the Communists weren’t letting anybody see *their* POW camps.

Upon entering the barracks, the paratroopers found North Korean POWs who had been tortured to death and left to hang as an example for others. Plans were found for the mass escape, slaughtering all in their path, to include the hospital nurses, before they themselves were killed.

The designated attack date was June 20th. The paratroopers assaulted on June 10th. Boatner had won the race. Somehow, the Republic managed to give him one more star before he retired.

One has to wonder about Abu Graib prison. Unlike Koje-do, at peak they only had 4,000 prisoners. Some of the lessons of Koje-do should have been clear. Only top quality staff should run such an institution, and any faults or slip-ups would be trotted out before the world and harm the interests of the United States.

Koje-do is mainly known these days for its shipbuilding. There is a museum with various scale dioramas dealing with the camp. A small compound with tents and various facilities that tourists can walk through, including a full-scale model of prisoners squatting over honey buckets, and, in the usual Asian manner, a POW with his “chaloga” out at the latrine.

Even more tasteless, large boards with paintings of POWs looking out through wire are on display, with holes for tourists to stick their faces through to be part of the picture. Otherwise, it is a good model of the camp.

As for the three North Korean senior leaders at Koje-do who failed in their mission, they all survived and were repatriated to North Korea. Pak vanished from sight, and the other two were shot.

Author’s Note

For more information on the Koje-do prison camp, the author recommends:

- General Haydon Boatner

- Behind the Wire: Koje-do Prison Camp

- Deployment to Koje-do

- The Korean truce

- History of Koje-do

(Featured Image Courtesy: Jim Healy, UPI)

COMMENTS