In late November 1863, President Lincoln gave perhaps one of the most important speeches in American history. On the 19th of November that year, the government was dedicating the National Cemetery at Gettysburg Pennsylvania where the bloodiest battle of the Civil War had been fought just a few months before.

Between North and South, there had approximately 51,000 casualties in just a three-day period between July 1-3, 1863. General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia was moving across Maryland and into Pennsylvania for his second (and last) invasion of the North. He had hoped to threaten Washington and get the Union government to agree to peace and allow the South (Confederate States of America) to be its own country. Lee had 75,000 men under his command.

Opposing him was George Meade’s Army of the Potomac. Meade had just taken command and was cautious as Lee had regularly whipped every Union commander that he did battle with. Meade had 104,000 troops at his disposal.

Part of Lee’s command, North Carolinians under General Johnston Pettigrew ventured into Gettysburg to hunt for supplies, mainly shoes, as much of Lee’s army was barefoot. Pettigrew’s troops met advanced cavalry of the Union commanded by John Buford. Pettigrew reported to his commander Harry Heth what he had seen. Against Lee’s orders of beginning a general engagement before the entire army could be brought to bear, Heth brought two brigades into Gettysburg the next morning and pushed the cavalry out of town. The battle was on.

The Union controlled the high ground outside of town, Lee’s forces crashed against them on their left flank at Little Round Top, the Devil’s Den and the Peach Orchard. While also Lee attacked the Union’s right at Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill. Both sides suffered heavy losses, but the Union’s lines held. On the third day, Lee concentrated his forces and tried to assault the middle of the Union line with George Pickett’s division.

Pickett’s Charge as it became known was thrown back with horrendous casualties as Union rifle and cannon fire decimated the Confederate troops charging across a mile of open ground while steadily advancing uphill. Lee’s army retreated back into Virginia.

Shortly after the battle, the dead which littered the battlefield were buried in hastily dug graves as was the custom. But the locals petitioned the government to mark the burial ground as a national cemetery. Originally, the date for the dedication was set to be October 23, but the featured speaker for the dedication Edward Everett said he needed more time to prepare so the event was moved back to mid-November. President Lincoln was not the featured speaker of the event, contrary to what many people believe. However, he was invited by the founders of the national cemetery movement led by local attorney David Wills to “formally set apart these grounds to their sacred use by a few appropriate remarks.”

Although the war was far from won as 1863 wore down, Lincoln was encouraged by the two huge victories won in the East at Gettysburg and in the West, where General Ulysses S. Grant had defeated the Confederates at Vicksburg, cutting the Confederacy in two and handing over control of the Mississippi River to the Union.

Lincoln was especially pleased that both battles ended on July 4th, Independence Day and he decided to write his remarks on the significance of the war and the Declaration as he pointed out that it and not the Constitution was the foundation that our founding fathers laid out for our new nation.

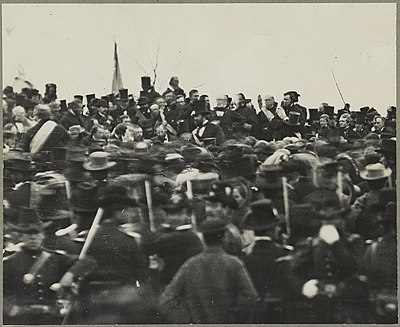

On the cloudy day of November 19th, a band played and then Everett spoke for over two hours, as was the custom for the time. When Lincoln rose, his speech was extremely short, only 272 words. Lincoln’s speech took just two minutes. But the 15,000 people in attendance would remember his words long after Everett’s would fade from memory.

Later Everett would write to Lincoln to address his admiration for what he conveyed in just a very short amount of time. “I wish that I could flatter myself that I had come as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours as you did in two minutes,” he wrote to the President.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Lincoln evoked the Declaration of Independence and his words conveyed that this great Civil War was the test to decide whether this new nation brought forth by our founding fathers would survive. His speech in its entirety is here.

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth, upon this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met here on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of it as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled, here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they have, thus far, so nobly carried on. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they here gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain…

That this nation shall have a new birth of freedom; and that this government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Lincoln received criticism from Democratic newspapers after the fact that his speech was too short and inadequate for such a momentous occasion. After his assassination, however, Senator Charles Sumner from Massachusetts, “That speech, uttered at the field of Gettysburg…and now sanctified by the martyrdom of its author, is a monumental act. In the modesty of his nature, he said ‘the world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.’ He was mistaken. The world at once noted what he said, and will never cease to remember it.

COMMENTS