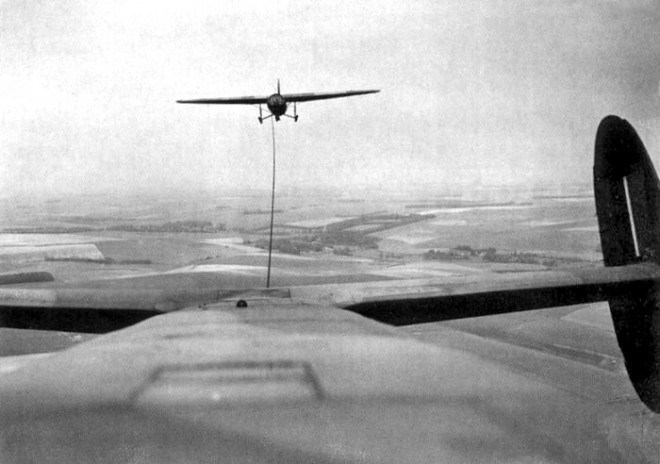

They passed below 100mph, the ground rising fast. In the lead glider were Howard and an assault element under Lieutenant Den Brotheridge. Their pilot Jimmy Wallwork performed what was later called ‘one of the most outstanding flying achievements of the entire war’ when he brought his glider down at 80 mph beside the canal, heard its landing gear shearing off, sparks flying and a slam to sudden stop which knocked most onboard unconscious. The 2 other gliders came in and landed perfectly behind them as if placed there by hand.

In seconds, onboard the three, men roused from their confusion. As Howard later recorded: “The dazed silence did not seem to last long because we all came to our senses together on realizing there was no firing. No firing! It seemed quite unbelievable…”

Men began pouring from the craft, spilling into and around the trenchline, racing for the bridge an incredible 47 yards away.

Paras dumped grenades into the pillboxes as Brotheridge led them across the bridge, shouting their platoon signal “Able! Able! and firing all the way as the pillboxes exploded. They shot down startled sentries while others fled into the night. Other Germans got off a few shots and dropped a para before falling themselves under a hail of bullets.

Someone stooped to see who it was. His stunned look revealed the casualty…Brotheridge. He was later dragged away from the charge which continued unabated down the road. After setting him down the orderlies struggled to revive him. It was too late. Brotheridge became the first Allied death of D-Day.

Someone stooped to see who it was. His stunned look revealed the casualty…Brotheridge. He was later dragged away from the charge which continued unabated down the road. After setting him down the orderlies struggled to revive him. It was too late. Brotheridge became the first Allied death of D-Day.

Paras tasked with clearing the bridge of planted explosives hung on the under sides feeling for the charges. They returned to Howard with startling news. There were none. Further search revealed the demolitions stored in a steel container nearby.

Firing subsided after a few minutes and Howard took stock of the situation. They suffered two dead but secured the bridge intact. At that moment, his men began setting up positions to prepare for the expected counterattack. He deemed the situation satisfactory enough, though, to order broadcast of the codeword for success. ‘Ham.’

Simultaneously, as Howard’s Paras battled at the canal bridge, two gliders under Captain Brian Priday descended to land a few hundred yards away from the Ranville bridge. Men poured from their aircraft, except Priday was not among them. His glider had landed miles away at another bridge due to a tow plane’s navigation error.

Now, it was up to lieutenant Dennis Fox to assault the bridge. He moved in with his element and charged like Brotheridge, yelling the platoon name ‘Fox! Fox!’ only to see sentries scurry away without firing a shot. A machine gun emplacement opened up, breaking up the rush. Paras dove for cover as one of their own fired his light mortar and planted a round square on the threat, disintegrating it in a flash.

They found all other enemy positions empty as they scoured the bridge for the explosives. None were found until later, stored in a nearby house used as a billet. Ranville fell. The codeword ‘Jam’ was sent, and soon, ‘Ham and Jam’ sounded over the airwaves back to Britain.

Both objectives now belonged to the British. All of it had been done in less than 10 minutes.

In the next phase of Operation Tonga, a couple of miles away hundreds of 5th Brigade reinforcements blanketed the sky in their parachutes, guided by pathfinder lights emplaced on the ground. They formed up and moved for the two bridges, arriving 90 minutes later with only 700 of the 2,200 reinforcements due to transport pilots navigation errors and high winds, which Howard realized had scattered them over a wide area.

700 men would have to do.

As hours crept toward dawn, a series of individual actions played out. One, the German commander of the garrison responsible for the bridges was ambushed as he raced back in a staff car from his girlfriend’s house. His driver was killed and he was wounded, becoming a nuisance to the Brits as he raved about how they would be defeated by the ‘Master race, soon.’ A shot of morphine shut him up.

Another more pressing issue appeared in the form of a lone Panzer coming up the road near Benouville bridge. Several PIAT guns had been brought along by Howard. PIAT guns (Projector Infantry Anti Tank) were a spring loaded spigot launcher that lobbed small mortar like bombs out to 60 meters. Unfortunately, all except one PIAT gun remained unusable due to damage sustained during the landings.

With a paratrooper’s greatest fear coming toward them, it fell to Sergeant ‘Wagger’ Thornton to deliver the killing blow.

He set up of the side of the rode hearing the squeak of the treads approaching in the darkness. He had but two bombs to fire. In reality, he knew it would be one, because of the time the PIAT needed to set up a second shot. It was now or nothing, and as he saw the vehicle’s silhouette begin to outline and grow he waited until the last possible second and fired.

The bomb launched and struck home in a mighty flash of sparks and flame. The vehicle stopped and continued burning brighter, ever fiercer, illuminating the area for several minutes, and staying motionless in the middle of the road blocking further traffic.

More attempts, though not with armor, came as night gave birth to day. Yet every action by the Germans to dislodge the British fell short. Reinforcements from lost units kept trickling in, and soon the naval armada began arriving offshore.

In a few hours, Howard and his men became part of history as a column of infantry from the beaches marched toward them. They had done it. In those critical hours on which the fate of the free world hinged, the Ox and Bucks held until relieved.

(Featured Image Courtesy: Wikipedia)

This article previously published on SOFREP 12.09.2012 courtesy of Mike Perry.

COMMENTS