For proper functioning, the French armies needed considerable logistics. According to general principle and, more importantly, Napoleon’s mandate, French soldiers acquired daily needs directly from the occupied country. The Army’s commissioners usually issued contracts with some local suppliers, which were regularly paid. Nevertheless, outside the urban centers, looting and thefts were common. The guilty ones were soldiers who, with officers’ collusion, vented against the unarmed peasants, fueling a feeling of hatred toward the occupiers.

The insurrection of Madrid gave rise to other popular uprisings in all the Iberian provinces: the guerrillas began to organize, obtaining in some cases the support of the Spanish regular army and local gentry, too.

A good example of this association is found in the Principality of Asturias, one of the first provinces to rebel after Madrid’s riots. The capital, Oviedo, included both eminent personalities and ordinary citizens who formed a junta central as a unified front against French invaders. After ten days of secret preparation, the Council of Oviedo, followed by members of the surrounding villages, formally declared war on Napoleon by ordering a military enlisted of 18,000 men.

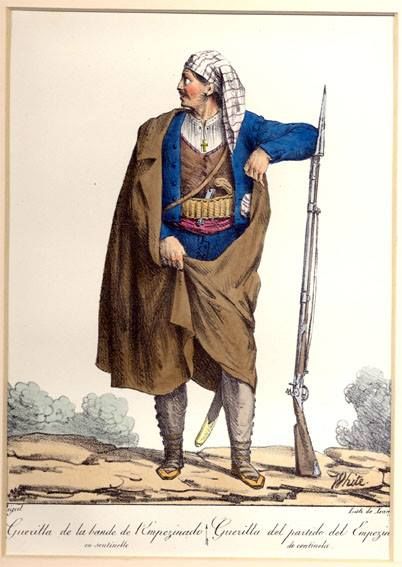

What happened in Asturias inspired others who took the initiative by establishing a semi-regular government. December 28, 1808, Madrid’s junta central issued a decree aimed at ensuring the coordination of all gangs of guerrilleros, submitting them to the local military authorities. The junta’s edict didn’t achieve any results because the resistance groups were based on small family groups that weren’t inclined to follow discipline or hierarchies. Among the bands of guerrilleros — or partidas guerrilleras — emerged some prominent figures whose heroic deeds against the French became legendary.

The Spanish resistance fighters were absolute masters of the territory. Spain’s geographic conformation, especially in the mountainous regions, was ideal terrain for ambushing and assaulting isolated or numerically inferior French columns. For Napoleon, who confided to solve the Spanish campaign in a few months, the raids of the guerrillas were a serious problem because they endangered lines of communication and distracted men from fighting the main enemy: the Duke of Wellington.

The French Strategy

The partidas’ capillary action made the Spanish peninsula an ungovernable place. To combat the guerrilla, there were no effective tactics other than repression, occupation of strategic points on the road system, and the preparation of “flying columns” ready to intervene.

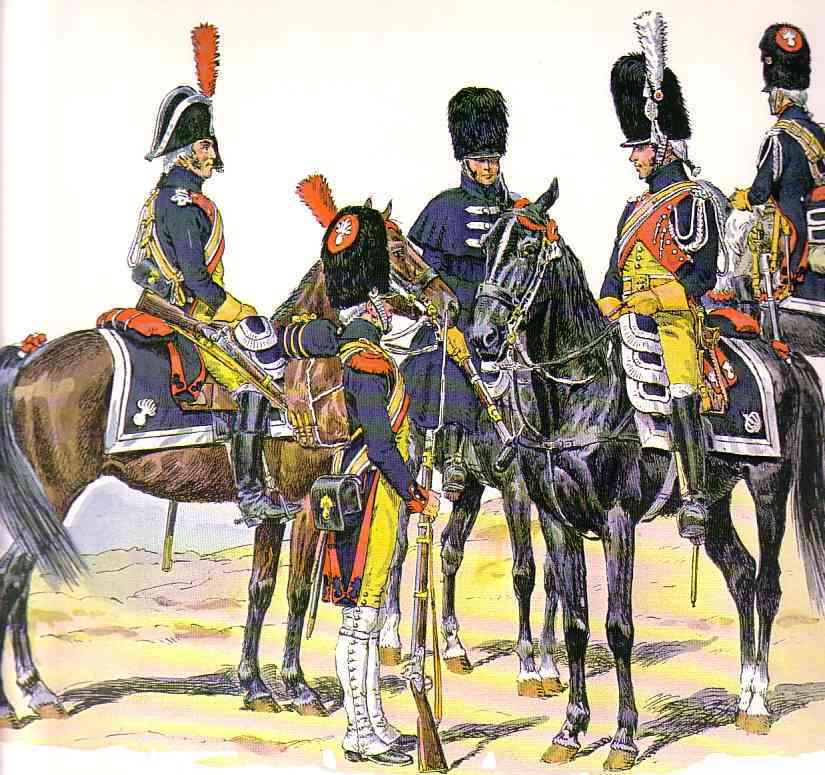

The main control instrument put in place by Napoleon — perhaps the most trusted — was the Gendarmerie Impériale, a specialized police force. On November 24th, 1809 the Emperor established the formation of 20 additional squadrons of Gendarmerie mounted and infantry units destined for the Iberian front. In 1811, the gendarmes were divided into six legions who became the Gendarmerie de l’Armée d’Espagne and dispatched throughout the territory with the task of overseeing the main communication routes that connected the cities.

The choice to supervise rather than actively fight the guerrilla proved unsuccessful because it deprived the gendarmes of overall control in the territory. It also prevented them from gathering information. “When the Gendarmerie moved to occupy a country it frequently fell into ambushes, and the real difficulty,” wrote Commander Honoré Reille, “it was not colliding with the guerrillas, but finding them.”

The clash between the two contenders reached a level of unprecedented brutality, with several episodes of summary shooting and terrible mutilations and bodies exposed to the public. It was a warning both for people who followed the guerrillas and for collaborators with the French. An all-out war that, once finished in 1814, marked the destiny of a country to oppose, even for several years, entire rebel provinces. The historian Michael Broers compares Spain to a “reign of the guerrilla war” replaced by a quick restoration of the state authority. The bands of Francesco Espoz y Mina, for example, continued guerrilla warfare activity beyond 1814, opposing the Bourbons’ monarchical restoration.

A Reflection

What happened in Spain between 1808 and 1814 helps to historicize insurgencies and guerrilla phenomenon, and pose questions regarding the Spanish peninsula conflict as a litmus test to better understand what happened in Iraq with the liberation war wanted by the Americans.

Perhaps a comparison is risky. Nevertheless, there are similar and divergent points which concern the invaders or liberators. In Spain, as in Iraq, two deeply differing cultures clashed. On the Iberian Peninsula, the main actors were imperial France: endowed with a modern army and an evolved government that presented itself as an example of social justice; and Spain: defended by a mismanaged armed force, and governed by an unstable monarchy that reigned over a retrograde society shaped by superstition and bigotry.

It’s not difficult to play with words, replacing protagonists’ names to realize how both France and America have similarities of political value on the international scene. Just as within Spain and Iraq a legitimate spirit of rebellion against undue and unwanted interference coexists with the government. There’s not ideological contiguity between Navarre’s guerrillero and Mosul’s rebel. However, if we exclude the infamous jihadi ideology, the case fits perfectly into the eternal debate that separates terrorists from guerrillas or freedom fighters.

The factor by which French and Americans diverge is the consequences arising from their conquests. When the Imperial Army crossed the Pyrenees and Murat massacred defenseless civilians in Madrid, the Spanish people made a common front, a single liberation movement, composed of multiple bands of rebels, but all pursuing the same purpose. The Iberian outbreak created a myth of invincibility that enveloped Napoleon’s troops. Between 1808 and 1814, the Spanish front involved 300,000 soldiers — and approximately 250,000, not counting the thousands of victims among the locals. In addition to an exorbitant cost in terms of human lives, the imperial funds suffered terrible bleeding with an outlay of about 800 million francs, an incredible figure for the time.

In 2002, the American presence in Iraq not only aggravated a situation already compromised by corrupt politicians and puppets swept by Washington but also caused a terrible civil war with no way out.

This article was originally published in January 2019. It has been edited for republication.

Some good books on Guerrilla Warfare:

Guerilla 1808-1814: Napoleon’s Spanish Nightmare

U.S. Army Guerrilla Warfare Handbook

CIA: Manual for PSYCHOLOGICAL OPERATIONS IN GUERRILLA WARFARE

U.S. Army Improvised Munitions Handbook

COMMENTS