“OK,” she said and glanced over at me. “Let’s give him ten more of morphine now,” she stated with a question in her eyes. I nodded.

“Give it in his buttock, please. His IV isn’t working, and we need IV access,” she directed.

“I can’t see or feel the veins to get a needle in. He has lost too much blood,”

The medic was trying to start a new IV line. He replied he could not find a vein or much of a pulse.

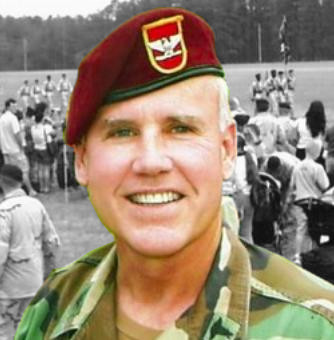

“Doctor Dobson. Time for your magic, please. If you can get an IV in a newborn baby’s scalp, you should be able to get an IV started somewhere,” I stated encouragingly. He was a pediatrician.

He moved his athletic five-foot nine-inch frame to the table and reached for a small 23-gauge butterfly needle. He stretched out the long, small-bore, transparent tubing attached and went to work. After a few attempts at the left arm and both feet, he claimed defeat.

“I can’t see or feel the veins to get a needle in. He has lost too much blood,” he stated with concern.

I had been going through the ATLS (Advanced Trauma Life Support) course in my head and decided to try something I had only done on animal patients before.

“Go to the call room please, and bring me the ATLS manual, on the first shelf next to the bed,” I requested to the medic nearest me.

“We are going to try a venous ankle cut-down.”

I found the page I needed, opened the book, and placed it between the legs of our patient. “There’s a large foot vein that runs behind the medial ankle bone.” I began to instruct as I went.

“I will make a cut in the skin here, above the medial malleolus, and dissect down until we find the large saphenous vein.” I made the cut precisely, and the patient moaned again. The medic dabbed away a small amount of blood and redirected the surgical light to the wound area.

“Look. There it is,” I pointed with the scalpel. “It’s right next to a small nerve. I am going to lift it up so you can get a suture under it,” I directed. The medic helped in awe.

We ran the suture under the pale vein, and I made a small nick in the surface of the vein. This allowed us to thread a large-bore IV catheter into the vein. I tied it in place with the sutures, rolled the skin back in place, and reached for the IV bag control device. It started to flow rapidly, and the room erupted in applause. I received high fives from Doctor Dobson and my medic.

“Wow. That was the first time I’ve done that on a human,” I noted, pretty proud of myself.

“Let’s use this access to give him ten more milligrams of morphine and get him into our ambulance. We need a medic to go on the transfer,” I finished.

“doctors do not go on ambulance transfers. It is too risky.”

Ten minutes later, Doctor Dobson was in the ambulance with the young medic showing him how to draw up the correct dose of morphine from a larger vial. The medic was concentrating.

“OK, Doc, come on out. We need to get the show going. They’ve got a three-hour ride ahead, through bad guy country,” I stated. The only light was from the red glow inside the ambulance. Darkness surrounded us. He and I both knew regulations stated that doctors do not go on ambulance transfers. It is too risky. Doctors were in short supply, so it was the medic’s job.

“Sir, I need to go,” he stated with a pleading expression.

“Craig, you know the rules. I need you here,” I stated sympathetically.

He repeated it with a concerned emphasis that got my attention. “Sir, I need to go.” I thought about it and knew he and I would both be taking a risk if I let him do this.

I made a command decision based on permission from our battalion commander that allowed us to go with our gut feelings. He was not telling me something.

“OK, Craig, you can go. But you get the first helo back here in the morning. Promise?”

“Yes, sir,” he replied with relief in his voice. His dark brown eyes were steady and determined as he returned to the task of keeping the patient alive.

He returned the next morning by hitching a 3.5-hour ride back on the returning Division armed convoy.

>He came to report in and thank me for letting him go.

“Welcome back. What was that all about last night? You put me in a tough spot.”

“Bob, that medic you sent with me was scared to death. I could not get him to understand simple instructions about giving the pain meds. I was almost sure our patient would die during the trip, and I did not want that on his conscience. His death needed to be my responsibility alone.”

I was taken aback by this. His risky request and my rule-breaking decision had happened because he wanted to protect the future psychologic health of our medic.

I regret to this day that I did not put him in for a medal for his act of compassion and heroism. I did make sure, years later, that he knew of my deep respect for his character and the decision he made that night.

Commentary: (Everyone in the room was angry at the man who had tried to kill our fellow teammates. We did not care about his pain as much as we would if it had been one of our own. But there was no question in anyone’s mind that our primary responsibility was to save lives. There was a common understanding that this casualty had wanted to die to take as many of his enemy with him as he could.)

We wanted to let him live.

That was what they trained us for, and that was what we did. We hoped that one day his children might live in a peaceful world.

Dobson added the following after reading this chapter.

“The route of the convoy was an interesting detail. Fallujah was in enemy hands. It was not taken until April 2004. We went to our battalion commander and explained that the casualty wouldn’t survive the 3.5-hour route around Fallujah, but if we used the black (off-limits) route of the highway through town, it would cut the time to less than an hour. The decision was made to take the faster route because in the horrible weather (sand/rainstorm) and at night, the enemy would never suspect a U.S. convoy blowing through town.

The convoy commander came to me and asked, Doc, how fast can we drive with your casualty?

Fast as hell, Sergeant. Just don’t wreck.”

They did precisely that, and the patient lived. My hero!

This is a chapter from my book Swords and Saints A Doctor’s Journey.

COMMENTS