**Editor’s Note: This loving tribute was written by noted author Frank Bill about his father, who passed away last night. May he rest in peace. – GDM

—

Sitting down with my father to discuss a routine mine sweep, this was not something he cared to offer details about at first. Men of war, like my father, do not elect to speak openly or brag about what they encountered. They do not confer about those shapes that lay strung over the earth, damaged and parceled like roadkill. Those men he bonded with, trained with, served with, and depended on when the shit hit the fan. When those souls did not make it back alive, but he did, it was too much to accept. What some refer to as survivor’s guilt.

The events from that day created a constant ringing in my father’s ears and haunted him for fifty-three years. Every night, when his eyelids clasped, and he searched for rest, his mind drifted on that memory skiff into tossing and turning that amped through his frame, delivering the mumblings of: “Get down! Shoot! Shoot! Get in the hole!”

But these were the events, the actions, that delivered that ringing in my father’s ears. Events he never told me about when I was a kid.

On July 27, 1968, around 6 a.m., my father and four to six Combat Engineers moved down the tank-tracked roads that led in and out of Da Nang. Their expectancy was on lifeline zero, coming from headquarters on Hill 37, 3rd Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment. Their mission was to sweep a ten-foot-wide swath of dirt for land mines and booby-trapped ordnance to deliver a convoy of food, water, ammo, and supplies to a military outpost on Hill 52.

It was a three-to-four-mile tension grinder through a Redline zone, meaning free-fire. A Leatherneck’s life could end with the explosion of gunfire from North Vietnamese Army snipers hidden within surrounding hamlets or an ambush from elephant grass brush lines that camouflaged the enemy. This expanse of tracked-over soil was flanked by green fields that turned to mud when it rained and sometimes cut through villages of 12×12 huts built from dried grass and bamboo, with flat dirt floors hardened like cement.

The Combat Engineer’s job was to discover and destroy mines of all dimensions. They blew enemy bunkers, bridges used by the North Vietnamese Army, and weapon caches found during search-and-destroy missions.

Unlike the thirty days of survival training my father received at Camp Pendleton, where they hunted and cooked hares and studied World War II anti-tank mines, Vietnam offered no such familiarity. There were no rabbits. Mines were handmade by the enemy, often constructed from unexploded American ordnance. The only saving grace was that many were stored in caves, drawing moisture and sometimes failing to detonate.

The enemy used scrap lumber and bamboo secured around explosives, placing nails against blasting caps. With enough pressure, the device ignited C-4 putty molded to the charge, capable of rearranging tank armor or dispersing a grunt into fragments of human anatomy. These devices were buried beneath tank track impressions and brushed smooth to hide any sign of disturbance.

That day, heat scorched down upon the engineers scattered across the road like lottery tickets waiting for their numbers to be drawn. Two tanks rumbled fifteen to twenty feet behind them, followed by grunts and the supply convoy.

Already have an account? Sign In

Two ways to continue to read this article.

Subscribe

$1.99

every 4 weeks

- Unlimited access to all articles

- Support independent journalism

- Ad-free reading experience

Subscribe Now

Recurring Monthly. Cancel Anytime.

Coming from Hill 52 in the opposite direction was a team of Army of the Republic of Vietnam soldiers conducting their own sweep. The two units would meet somewhere in the middle.

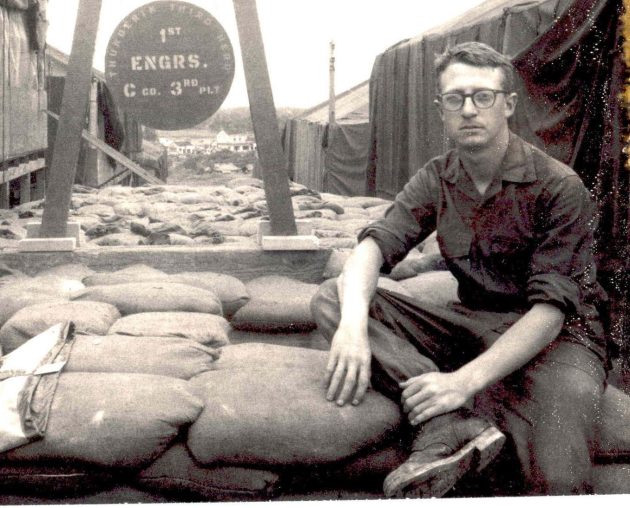

Wiry and thin, my father, Lance Corporal Frank Bill, gripped his mine detector. The tool resembled a weighted weed eater with a cafeteria plate attached to the end. His load included an M16 rifle, seven magazines of ammunition, grenades, a Ka-Bar knife, an M1911A1 .45 pistol, flak jacket, canteen, first aid supplies, blasting materials, and a helmet that weighed heavy on his head.

The detector itself was useless. The ground was saturated with shrapnel, causing constant false signals. The engineers relied on their eyes, scanning for breaks in tank track patterns. When such an imperfection appeared, sphincter muscles tightened.

Ahead of my father, PFC Tony DiBlasio unknowingly walked over a mine that failed to detonate. Behind him, Corporal Larry Taylor from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, noticed disturbed soil. He knelt and began probing with his knife.

The explosion followed.

A cloud of heated debris punched my father backward twenty feet. Unconscious for a moment, ringing consumed his ears. Reality returned in fragments. Hands dragged him to his feet. Words failed him. Breathing had to be remembered.

Shell shock.

Taylor did not survive.

The only remains recovered were fragments of his knee, ankle, and radio equipment. He had struck a forty-pound anti-tank box mine.

My father rode the back of a tank to Hill 52, replaying the explosion in his mind as dust swirled around him and the buzzing in his ears continued.

Medical evaluations confirmed a ruptured eardrum and facial injury. Blood and fluid leaked for weeks. Doctors told him it would subside.

It never did.

He returned to duty, sweeping roads, destroying mines, conducting search-and-destroy missions, navigating the moral fog of villagers trapped between two forces. He understood their position. He imagined himself in their place.

In war, lines are not always clear.

Months passed. His tour ended in January 1969. He was awarded the Navy Commendation Medal for Operation Allen Brook and later the Purple Heart.

The ringing followed him home.

More than anything, it carried the same question he still asks:

Why them, and not me?

COMMENTS