During late January 1879, about 150 British soldiers, defending the mission station at Rorke’s Drift defended it against 3000-4000 Zulu warriors in a series of attacks. The British held on despite enormous odds and their bravery under the command of Lieutenants John Chard of the Royal Engineers and Gonville Bromhead was rewarded with an incredible amount of awards for valor. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded along with five Distinguished Conduct Medals.

This battle, during the Anglo-AZulu War, immediately after a British defeat at the Battle of Isandlwana on January 22, 1879, as the British began an invasion of Zululand.

Early Moves Set the Table for Battle: Rorke’s Drift, known as kwaJimu (Jim’s Land) was a mission station and the former trading post of James Rorke, an Irish merchant. It was located near a drift, or ford, on the Buffalo (Mzinyathi) River, which at the time formed the border between the British colony of Natal and the Zulu Kingdom. It belonged to the Reverend Otto Witt, a Swede. Mr. Witt’s church had been turned into a store by the British Army and a hospital.

Lt.Chard of the #5 Company of the Royal Engineers had ridden out Isandlwana early on the 22nd but was ordered back to Rorke’s Drift to prepare defensive positions for a company that was en route. His men had initially been sent to improve the ford over the Buffalo River.

B Company, 2nd Battalion, 24th (2nd Warwickshire) Regiment of Foot (2nd/24th) under Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead was detailed to defend Rorke’s Drift which had been turned into a supply depot and a hospital.

Chard was left in charge of the small garrison by Major Henry Spaulding who rode out to find the troops who were supposed to arrive from Isandlwana and were overdue. Chard rode down to the ford where he met two survivors from the defeat of Isandlwana. They were told that the Zulu were approaching the station.

Chard, Bromhead and Acting Assistant Commissary James Dalton held a meeting to decide what their course of action should be. It was decided that a small force moving with carts and sick from the hospital would be easily overrun by the numerically superior Zulu force. They decided to stay and fight, defending the station.

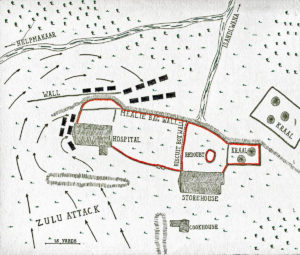

Building their Defenses: The men began immediately preparing defensive positions. The men built a defensive perimeter using mealie (corn) bags around the storehouse house, hospital and a stone kraal or animal enclosure. The building was built up with firing holes cut into the external walls with the doors barricaded.

During the late afternoon, the men were augmented by the Natal Native Horse, a troop of about 100 men commanded by Lt. Alfred Henderson who had retreated from Isandlwana. They volunteered to picket the large hill (Oscarberg), behind the station where the Zulu advance was expected to approach from.

Chard was optimistic they would be able to hold the position, he sent one rider riding hard to alert the garrison at Helpmekaar that they would soon be under attack.

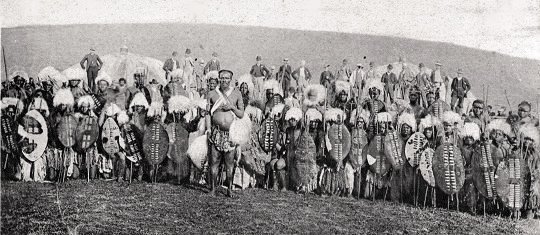

The Zulus were quickly approaching, having quick marched from their encampment some 20 miles arriving on the edge of Rorke’s Drift at 4:30 p.m. They had been marching for 8.5 hours. Their numbers were between 3000-4000 warriors from the “loins of the reserve” army at Isandlwana, although none were engaged there. They were referred to as the Undi Corps. They were led by Prince Dabulamanzi kaMapande, an aggressive leader who had hoped to capture the British base at Rorke’s Drift.

Most of the Zulu were married men in their 30s from the uDloko, uThulwana, inDlondo regiments and one regiment of young unmarried men from the inDlu-yengwe. Their mission was to swing wide of the main British army, severing their lines of communication and block their escape route back to Natal through Rorke’s Drift.

The Zulu swept up the hill at Oscarberg where the men under Henderson briefly opened fire, but short of ammunition, tired from the retreat and perhaps slightly unnerved from the events at Isandlwana soon fled to Helpmekaar. At the sight of Henderson’s men retreating, the Natal Native Contingent under the command of Captain William Stevenson bolted from the kraal, severely reducing the garrison’s strength.

Chard reacted quickly. His numbers now reduced, he was left with a bit more than 150 men, with nearly 40 in the hospital and only a handful of those able to take up arms. He reorganized the defenses and had biscuit boxes brought up to construct a wall through the middle of the post in order to make possible the abandonment of the hospital side of the station if need be.

500 of the Zulu warriors appeared around the hill to the south, running towards the mission station. The British were ready and unleashed heavy fire from the garrison and, at some fifty yards from the wall. The Zulu veered around the hospital to attack from the north-west. They were driven back by the fire from the garrison and went to ground in the undergrowth.

Most Zulu warriors were armed with an assegai (short spear) and a cowhide shield.The Zulu army drilled in the personal and tactical use of this weapon. Many Zulus also had old muskets and antiquated rifles, although their marksmanship training, as well as their ammunition and powder, were poor. They captured about 1000 Martini-Henry breech-loading rifles and plenty of ammunition at Isandlwana, but few if any of those found their way to Rorke’s Drift.

The main body of Zulus came up and opened a heavy fire on the British from cover around the west and north-west of the mission station. The situation was one where Chard realized that he couldn’t hold the north wall and the hospital was becoming untenable. The firing ports used by the British soldiers required the rifles to poke out and there the Zulu were grabbing them and attempting to pull them away. However, the Zulu were also firing their own weapons thru the ports if left empty.

Five of the defenders of the hospital were awarded the Victoria Cross for their defense of the hospital. They were Privates John Williams, Henry Hook, William Jones, Frederick Hitch and Corporal William Allen. The men fought until their ammunition ran out and then used bayonets to keep their attackers at bay.

By 6:00 p.m. Chard ordered the troops to pull out from the hospital. Four of the troops defending the hospital were killed, either by bullets or by assegai. Two patients also didn’t survive.

With his perimeter shortened, the pressure didn’t ease much on Chard, it grew worse as Zulu attacks then moved towards the cattle kraal as the night fell. Zulu attacks intensified throughout the night. By 10:00 p.m. Chard ordered the kraal evacuated and his men were now confined to a tight perimeter around the storehouse. The light from the burning hospital aided the British in identifying and eliminating Zulu warriors.

The fighting continued to rage until midnight when the attacks began to slacken. Both sides were exhausted. The Zulu had begun their march 16 hours earlier and covered 20 miles and had gone right into a major battle. The vastly outnumbered British troops had been fighting for 10 hours and were running low on ammunition. At the outset of the battle, they had 20,000 rounds of ammunition. By morning only 900 rounds were left.

The Zulu kept up their harassing fire until 4 a.m. when the shooting stopped and the Zulu finally withdrew. They rested for three hours and a 7 a.m. a large force of Zulu warriors appeared on the hill, but no attack followed. From their high vantage point, they could see a large relief column of British soldiers led by Lord Chelmsford approaching. They then withdrew and the battle was over.

British casualties totaled 17 dead and 9 wounded out of just under 150 officers and men. Zulu dead numbered 351 around the compound, however once Chelmsford and the defenders went among the wounded, they showed no mercy after the slaughter at Isandlwana. They were thought to have killed another 500.

Awards made following the Battle of Rorke’s Drift:

Victoria Crosses: (Royal Engineers) Lieutenant John Chard R.E. (24th Regiment) Lieutenant Gonville Bromhead, Corporal William Allen, Privates Frederick Hitch, Alfred Hook, Robert Jones, William Jones, John Williams, (Army Medical Department) Surgeon James Reynolds, (Commissariat and Transport Department) Assistant Commissariat Officer James Dalton and (Natal Native Contingent) Corporal Ferdinand Schiess.

Distinguished Conduct Medal: (24th Regiment) Colour Sergeant Frank Bourne, Private William Roy (Royal Horse Artillery) Gunner John Cantwell and (Army Service Corps) Corporal Francis Attwood.

Both Lieutenants Chard and Bromhead were promoted to Major following their bravery at Rorke’s Drift.

There was at least one British officer who was outraged at the number of decorations given at Rorke’s Drift, which he took as the military white-washing the disaster at Isandlwana. Sir Garnet Wolseley, taking over as Commander-in-Chief from Lord Chelmsford later in 1879, was unimpressed with the awards made to the defenders of Rorke’s Drift, saying ‘it is monstrous making heroes of those who shut up in buildings at Rorke’s Drift, could not bolt, and fought like rats for their lives which they could not otherwise save.’

***Footnote:*** The Battle of Rorke’s Drift was brought to film in the classic 1964 film starring Stanley Baker, Michael Caine and directed by Cy Endfield. The film stayed true to the majority of facts surrounding the battle, using actual Zulu tribesmen as the extras with only a few minor inaccuracies.

Perhaps the biggest was that the Zulu sang to the British at the end of the film, saluting their courage as “fellow braves” in a show of respect. That never happened. The Zulu moved off when they saw the relief column approaching.

One other inaccuracy that stood out, from Wikipedia: Private Henry Hook VC is depicted as a rogue with a penchant for alcohol; in fact, he was a model soldier who later became a sergeant; he was also a teetotaller. While the film has him in the hospital “malingering, under arrest”, he had actually been assigned there specifically to guard the building.The filmmakers felt that the story needed an anti-hero who redeems himself in the course of events, but the film’s presentation of Hook caused his daughter to walk out of the film premiere in disgust.

Photos: Wikipedia/British National Archives

COMMENTS